You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Jen Kim/Inside Higher Ed

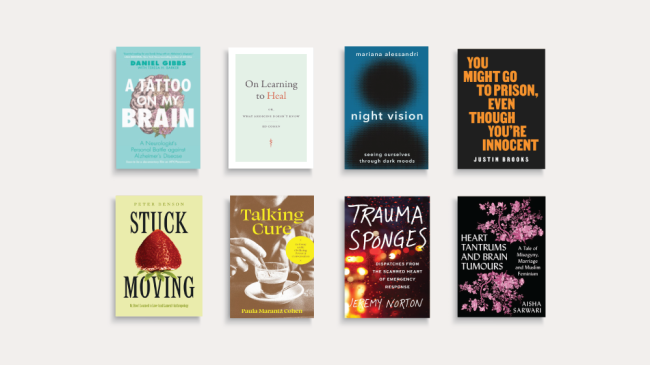

These seasonal overviews of forthcoming books from university presses usually focus on public and topical concerns: technology, the election cycle, pandemic impacts and so on. But several titles appearing in the spring catalogs stand out as narratives of personal difficulty.

The label “memoir” is probably more suitable for some than others. (The first-person singular need not be self-revealing; it can also be a matter of expository effectiveness.) The way these titles seem to cluster together is striking, in any case. They are studies in human vulnerability.

“Soon to be a documentary film on MTV/Paramount” is not the sort of phrase often appearing in university-press catalogs, but it accompanies the announcement for the reissue in paperback of the 2021 book A Tattoo on My Brain: A Neurologist’s Personal Battle Against Alzheimer’s Disease (Cambridge University Press, March), by Daniel Gibbs with Teresa H. Barker. Caring for Alzheimer’s patients was the author’s specialty for 25 years. Given findings from genetic tests, he was aware his own risk of susceptibility to the disease and “suspect[ed] he had Alzheimer’s several years before any official diagnosis could be made.” (All quoted passages in this article are taken from press catalogs or websites.) The book “documents the effect his diagnosis has had on his life and explains his advocacy for improving early recognition of Alzheimer’s,” drawing on the author’s extensive clinical experience.

From the other side of the consulting-room table, Ed Cohen’s On Learning to Heal: Or, What Medicine Doesn’t Know (Duke University Press, January) recounts a diagnosis of Crohn’s disease in his early teens, almost dying from it in his 20s, and medical advice “that the best he could hope for” over the course of his life “would be periods of remission.” Reflecting on “fifty years of living with Crohn’s,” he “consider[s] how Western medicine’s turn from an ‘art of healing’ toward a ‘science of medicine’ deeply affects both medical practitioners and their patients.” This should not be read as implying that the author has been cured. While the range and effectiveness of treatments have increased, Crohn’s remains as yet incurable. But he finds a model of psychological and spiritual treatment in the ancient Greek and Hellenistic temples to Asclepius, the god of healing.

Peter Benson’s Stuck Moving. Or, How I Learned to Love (and Lament) Anthropology (University of California Press, April) offers the self-portrait of “a professor affected by bipolar disorder, drug addiction, and a stalled career who searches for meaning and purpose within a sanctimonious discipline and a society in shambles.” The author turns “the lens of analysis” back on “the backstage of academic work and life, and the unbecoming self behind scholarship,” taking aim in particular at “the ableist conceit that anthropologists are outside observers studying a messy world.”

The situation Aisha Sarwari narrates in Heart Tantrums and Brain Tumors: A Tale of Misogyny, Marriage and Muslim Feminism (Oxford University Press, May) may not be messy, but it sounds overwhelmingly complicated. The daughter of Pakistani and Indian parents and “[r]aised to be a ‘good Muslim girl,’” she grew up in Uganda and continued her education in the United States, where she met Yasser, the Pakistani law student who would become her husband. After “they returned to their ancestral country,” Yasser developed a brain tumor, leaving him prone to violent outbursts. But how much was the abuse a matter of his illness and how much “of women’s place in an oppressive society”?

Making the best of miserable circumstances does not necessarily mean cheering up. Against the self-help industry’s ethos of obligatory good vibes, Mariana Alessandri’s Night Vision: Seeing Ourselves Through Dark Moods (Princeton University Press, May) turns to “a diverse group of nineteenth- and twentieth-century philosophers and writers to help us see that our suffering is a sign not that we are broken but that we are tender, perceptive, and intelligent.” Or at least we can be, following the example of those who “sat in their anger, sadness, and anxiety until their eyes adjusted to the dark,” finding a path to “wit and humor, closeness and warmth, and connection and clarity.”

Still, you might want to talk to somebody about it. Paula Marantz Cohen’s Talking Cure: An Essay on the Civilizing Power of Conversation (Princeton University Press, March) promotes communicating face-to-face “freely and without guile” as a course of treatment for “what ails our troubled society.” (Communication via social media doesn’t help and doesn’t count.) We “learn to converse in our families,” the author maintains, “then carry that knowledge into a broader world where we encounter diverse opinions and sensibilities.” That is clearly a best-case scenario, and the author “details some of the habits that can result in bad conversation.”

Justin Brooks cuts right to the chase, warning readers up front that You Might Go to Prison, Even Though You’re Innocent (University of California Press, April). The author’s courtroom experience plus “robust research on what we know about the causes of wrongful convictions” inform his discussion of “how any of us might be swept up in the [prison] system” because “we hired a bad lawyer, bear a slight resemblance to someone else in the world, or are not good with awkward silence.” And it’s endlessly astonishing what innocent people will confess to under pressure.

Written by a Minneapolis firefighter and emergency medical technician, Jeremy Norton’s Trauma Sponges: Dispatches From the Scarred Heart of Emergency Response (University of Minnesota Press, July) draws on 20 years of “sustained direct encounters with the sick, the dying, and the dead.” The author gives “a rare insider’s perspective on the insidious role of sexism and machismo in his profession” and tells of “respond[ing] to the scene of George Floyd’s murder” with his crew. The phrase “trauma sponge” refers to a first-aid item, though it has turned into a slang expression for someone whose shoulder is often cried on. Here it is repurposed to naming those who perform “the work of first response and last resort,” and routinely absorb more than the rest of us can even imagine.