You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

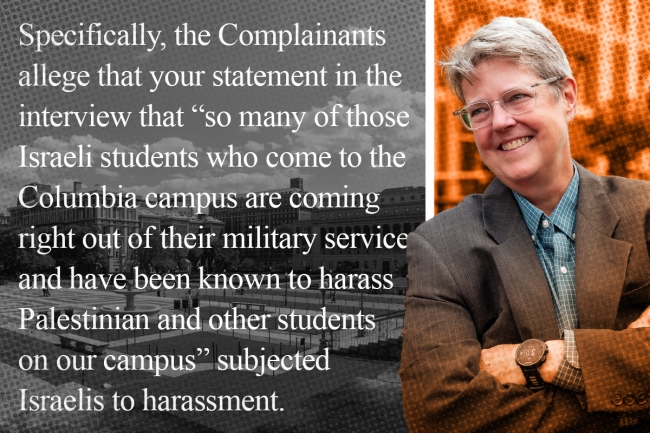

Katherine Franke, a longtime tenured law professor at Columbia University, says two colleagues filed a complaint against her that may lead to her firing.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | iStock/Getty Images | Katherine Franke

In January, pro-Palestinian protesters on Columbia University’s campus said they had been sprayed with a harmful chemical. Students were hospitalized. No arrests were reported.

Katherine Franke, Columbia’s James L. Dohr Professor of Law, told Inside Higher Ed that the left-leaning radio and television newscast Democracy Now! reached out to her about the situation because she’d been involved in defending pro-Palestinian student protesters from disciplinary charges.

In the Jan. 25 broadcast, host Amy Goodman said, “Eight students were reportedly hospitalized or seeking medical attention.” Goodman said protest organizers were accusing other students who had served in the Israeli military, saying they sprayed a weapon “known as ‘skunk’ that soldiers also deploy on Palestinians.” (The New York Police Department didn’t return a request for comment Thursday on what it ultimately found, and a Columbia spokesperson said the university doesn’t comment on student disciplinary matters.)

Franke told Goodman during the program that Columbia has a program through which it has a “relationship with older students from other countries, including Israel. And it’s something that many of us were concerned about, because so many of those Israeli students, who then come to the Columbia campus, are coming right out of their military service. And they’ve been known to harass Palestinian and other students on our campus. And it’s something the university has not taken seriously in the past.”

Most Jewish citizens of Israel must serve in its military: at least 32 months for men and 24 for women.

“We know who they were,” Franke told Goodman regarding the alleged attackers at Columbia.

She accused the university of using an attack “from those who support the Israeli government and the violence that’s being meted out towards Gazans as a kind of pretext to clamp down even further on peaceful protest by our other students.”

This didn’t remain a fleeting broadcast interview. It led, Franke says, to a university investigation that millions heard about when Columbia’s president, Minouche Shafik, revealed it in testimony on Capitol Hill in April.

Following their December grilling of the presidents of Harvard University, the University of Pennsylvania and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on campus antisemitism—televised proceedings that may have contributed to two of those presidents’ resignations—House Republicans called Shafik before the House Education and Workforce Committee.

“Let me ask about Professor Katherine Franke from the Columbia law school who said that all Israeli students who have served in the IDF [Israel Defense Forces] are dangerous and shouldn’t be on campus,” Representative Elise Stefanik asked Shafik. Stefanik, a New York Republican, had already earned popularity in some corners for her pointed questions in the previous hearing. “What disciplinary action has been taken against that professor?” she asked.

“I agree with you that those comments are completely unacceptable and discriminatory” Shafik replied. Pressed again, Shafik said Franke “has been spoken to by a very senior person in the administration, and she has said that that was not what she intended to say.” Later in the hearing, Shafik said that Franke was under investigation—making Franke one of multiple faculty members whom Shafik criticized and revealed investigations into during the hearing. Shafik said one visiting scholar “will never teach at Columbia again.”

“We are promised up and down that these internal investigations are confidential,” Franke—whose work focuses on antidiscrimination law in the areas of gender, sexuality, race and ethnicity—told Inside Higher Ed. She called the revelation of it a “real breach of my employment contract.”

Now, Franke, a tenured professor, said she’s heard that a report on her investigation is imminent, and she fears it may result in her firing after more than 22 years at Columbia.

Complaints From 2 Colleagues

Franke has been targeted before for criticisms of Israel. In 2018, she said she was leading a group of U.S. civil rights leaders in a visit to the West Bank but was detained en route at a Tel Aviv airport for 14 hours and repeatedly interrogated. She said her interrogators held up, on their phones, a dossier that Canary Mission, a group that tracks alleged antisemitism by professors and others, had assembled on her. The interrogators accused her of coming to spread the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement, which Franke denied.

She was refused entry and temporarily banned from the country. A spokesman for Israel’s Strategic Affairs Ministry told Haaretz it was because of her “prominent role” with Jewish Voice for Peace, which supports the BDS movement, but Franke said she wasn’t involved with the organization at the time. Franke told Inside Higher Ed that the university at the time “did nothing. They didn’t reach out to the State Department.”

“I’ve felt for many years like I’m hanging out here on my own,” Franke said.

But now her pro-Palestinian speech and actions may cost her her job. And she alleges Columbia’s investigation and possible forthcoming punishment are partly in retaliation for her helping legally defend hundreds of pro-Palestinian student protesters, including training other lawyers to do so. “There has been a concerted campaign by this university to punish what would otherwise be protected speech or political protest,” Franke said.

Franke told Inside Higher Ed that two of her law school colleagues, Zohar Goshen and Joshua Mitts, filed an internal complaint with the university in February. She provided a letter from the university, dated Feb. 13, saying the Office of Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action was starting an investigation after Goshen and Mitts alleged that she "harassed members of the Columbia community based on their national origin" in her Democracy Now! interview.

“Specifically, the complainants allege that your statement in the interview that ‘so many of those Israeli students who come to the Columbia campus are coming right out of their military service and have been known to harass Palestinian and other students on our campus’ subjected Israelis to harassment,” the letter says.

Goshen and Mitts didn’t return requests for comment Thursday, and Columbia spokespeople didn’t confirm or deny the veracity of the letter. One spokesperson wrote that “we will not comment on a pending investigation.”

The university did send a copy of its Office of Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action policies, which include termination as one of multiple possible sanctions for alleged discrimination and harassment. Franke says her lawyer has told her she has a 50-50 chance of being fired.

While these spokespeople may be silent about the investigation, the university president had talked about it on a national stage. Later in April, Franke appeared on MSNBC, calling Shafik’s comments an “appalling moment” and saying Shafik “knows I did not say those things. I have spoken to her about that. What Representative Stefanik was saying was an absolute lie and a fabrication.”

Franke has maintained that Stefanik misquoted her. A Stefanik spokeswoman said "the Congresswoman was paraphrasing reporting" from this article in the conservative Washington Free Beacon, which itself said it was paraphrasing a lawsuit from Students Against Antisemitism.

Franke went on to say on MSNBC, “I have discussed how we’ve had problems on our campus with certain people who’ve come to campus coming right out of their military service and that transition from the state of mind one needs to be a soldier to the state of mind one needs to be a student—[those] are different states of mind and that transition can be difficult.” She told Inside Higher Ed that her MSNBC comments now have also become part of the investigation.

Franke said she has used Shafik’s comments and the internal and public pressure on Columbia in her own defense. “The president of the university had already prejudged me on the record in Congress,” Franke said.

Franke said she also argued that the university “had a litigation incentive” to aggressively discipline her because Jewish students were accusing the university in lawsuits of tolerating a hostile environment for them by not sufficiently enforcing disciplinary codes.

According to Franke, she and her attorney successfully got university employees to step aside as the investigators, and an outside law firm, Sher Tremonte, is now investigating. “I was deposed on June 13 for a couple of hours,” Franke said. “It seemed pretty clear that the lead investigator had made her mind up already.”

It’s unclear what full process, and associated protections, Franke will have against termination. It’s an Office of Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action investigation, but university policy also says she is due a hearing arranged by the Faculty Affairs Committee unless it’s waived. Franke said she hasn’t waived it.

Greg Scholtz, a senior program officer in the AAUP’s Department of Academic Freedom, Tenure and Governance, said that Columbia’s administration, if it wants to take punitive action, should “present specific charges before an elected faculty hearing body, and they would be obliged to bear the burden of proof in that hearing to demonstrate that Professor Franke’s speech or conduct warranted sanction—keeping in mind that any serious sanction should be related directly and substantially to her actual performance as a teacher or researcher.” Scholtz said that “it would certainly attract the AAUP’s attention if she were to be summarily dismissed.”

Zach Greenberg, a First Amendment attorney at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, a free speech group, said Franke’s contested statement “to me is a political statement,” and “without more evidence it would still remain protected by Columbia’s free speech policies.”

If a tenured professor can be ousted for her speech, Franke said she fears what will happen to those with fewer protections, particularly in a possible second Trump administration. “If they can go after me for defending the students, what comes next?” Franke said. “Speech about abortion, critical of Trump, climate change?”