You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

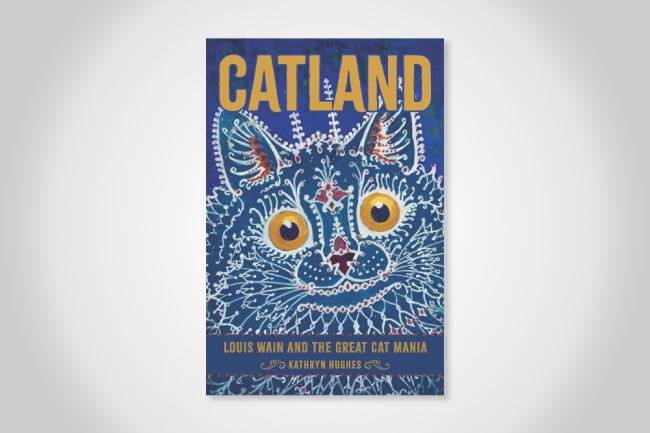

Johns Hopkins University Press

Hanging in our guest bedroom is a framed print depicting a classroom scene of the late 19th century, as imagined by the British artist Louis Wain (1860–1939), whose work was, in his day, familiar to a huge audience throughout the Anglophone world.

The one adult in the scene is a stern pedagogue; she wears a heavily starched bonnet and holds what would appear to be a handful of switches while standing near a chalkboard. On it, the traces of a multiplication lesson can be made out, along with a crude sketch of the teacher hanging from a gallows. It is a stick figure, but with a bonnet, precluding any deniability by the likely suspects nearby.

The teacher rails at them as the more studious pupils read their books, or at least pretend to do so. But things are about to get completely out of hand. One incorrigible dribbles ink on the teacher, while another aims his peashooter at her.

The picture is titled “Mrs. Tabby’s Cat Academy,” with the student body consisting entirely of kittens. All are as suitably dressed as their instructor. It is an exemplary scene from Wain’s enormous and once-ubiquitous body of work: a prodigious output of postcards, magazine illustrations, advertisements and books. The latter often featured his name in the title. He was, in effect, a brand. Not all of his output depicted cats, but most of it did.

In 1921, he was featured in a newsreel series called “Art Celebrities at Home,” whose makers took it as a given that the public would recognize Wain’s name and have fond feelings toward his work. (His comic depictions of well-dressed cats gathered to celebrate Christmas were almost a Yuletide tradition around the turn of the 20th century.) Thus, viewers of the newsreel would undoubtedly also want to see Wain’s own pet cat, if only to confirm that he had one. The cat looks more comfortable in front of the camera than the artist does.

By the 1920s, Wain’s popularity had already begun to fade. No doubt his Victorian and Edwardian cats looked old-fashioned to a generation growing up with Krazy Kat (in the newspapers) and Felix (on the silent screen), whose antics were a bit edgier. But Wain got there first. He was the popular artist who, besides drawing cats, also put clothes on them and pictured them kissing under the mistletoe. He invented the anthropomorphic feline, a species that remains alive and well now in a very different media landscape.

But perhaps that is putting things the wrong way around. Among the numerous insights that Kathryn Hughes offers in Catland: Louis Wain and the Great Cat Mania (Johns Hopkins University Press) is that the artist did not always draw cats as humanlike so much as vice versa. (The author is an emerita professor of life writing at the University of East Anglia.) Sketching people and social situations, Wain added the muzzles, fur and tails.

Satire often reduces human behavior to its closest animal equivalents. Wain’s satire is gentle, and at times almost indistinguishable from whimsy, but Hughes finds aspects of his life that would justify some wariness toward our species.

Hughes’s Catland provides the richest and most comprehensive account of Wain’s life and times available and brings out nuances and connotations of his imagery that would be easy to miss. The artist was born with a cleft lip and was kept out of school until he was 10 years old—per the medical advice of the day to keep a child at home until that age, in hopes the cleaving would heal. Throughout his adult life he wore a mustache. But hiding the deformity was not an option at school, and it made him a target of bullying. Hughes points out that the artist revisited schoolroom scenes almost compulsively, and that the pictures are “saturated in violence,” however comical in tone.

The home he grew up in was also a business, turning out religious garments for churches. His parents and sisters were embroiderers, while Louis was expected to turn his knack for drawing to the design of new patterns. And while he eventually found paying work as a freelance commercial and magazine illustrator, his personal life and finances remained intertwined with those of his widowed mother and his sisters, who all remained unmarried. If the burden of responsibility were not enough grounds for anxiety, the family’s social status was constitutionally unstable. As business owners they were middle-class, but the vagaries of the marketplace were a constant strain. Certain shady practices were involved in keeping the enterprise running at times, and the family had to move a lot, often without leaving a forwarding address.

The expression “shabby gentility” hardly suffices to characterize this way of life, which was a constant losing race against bankruptcy. And Wain did not escape the rut, despite saturating the commercial art market with his cats. Living from crisis to crisis developed the force of habit. The wisdom of contractually obliging royalties for his work was lost on him. If he had an accountant or lawyer, Hughes has not discovered him. Wain clearly did not have many associates averse to taking advantage of him.

Most recollections of Wain describe his manner as withdrawn and his conversation as often peculiar. It got stranger as paranoid delusions occupied more and more of his attention. In June 1924, he was committed to the paupers’ wing of an insane asylum. A number of prominent writers and well-wishers took up a collection to move him to a better facility and provide him with art supplies. The gentleman put in charge of the fund embezzled most of it in short order.

Once again money was raised to continue supporting Wain, and the remainder of his life was as productive and comfortable as anyone’s could be while confined to a psychiatric facility. That the artist did not die homeless must be regarded as a rare instance of good fortune.

It is a grim story, but Catland is not a grim book. It is only the second biography of Wain (unless you count a book its author calls a “fictionalized biography”), and it incorporates a much broader and deeper pool of source material than was available to his other biographer. The chapters alternate between his productive and complicated life and related developments: the rise of cat breeding and competitions, changing British cultural mores, the social scene in beach-resort towns the arrival of Postimpressionism and subsequent artistic outrages … The nonbiographical chapters could be read as freestanding essays, learned though informal in style. But in context they constitute a kind of thick description of what’s going on in the illustrations (which are abundant and aptly selected).

The most obvious referent for Catland is the universe of Wain’s graphics, populated by felines of every age and social position. A mother bakes a pie; her family gathers around to admire it, with all the rat tails coming out of the crust. Other cats meet, argue, flirt, hire lawyers, take vacations, menace or snub one another, attend parties, marry and have children (or regret marrying and having children), etc. Wain’s Catland aspires to capture the tapestry of ordinary human experience, at one remove.

But the characters he depicts are also creatures of their time and place—namely the British Empire at the height of its power and prosperity. Hughes calls Wain a “passionate patriot and confirmed imperialist.” In Wain’s Catland, jingoism is rarely in evidence, but its inhabitants are confident of their society’s place in a world it has, in large part, conquered. And in that respect, the success of Wain’s style and vision is something like a variety of soft power.

Cat enthusiasts are notoriously prone to subjecting others to more of it than is wanted. If you’ve read this far, you are almost certainly a fellow cat person, and I will end this monologue by recommending Catland to your attention without reservation.