You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Warner Bros. Discovery

Last week, The New Yorker published “The End of the English Major,” by Nathan Heller. English faculty members took to Twitter to push back on virtually every point in the essay. English B.A.s responded in droves to the poet Jorie Graham’s call to declare #IWasAnEnglishMajor, recounting how their undergraduate training led to remarkable careers.

But Heller is one of many to spot the four horsemen—call them defunding, recession, self-sabotage and artificial intelligence—on the humanities’ horizon. The last two horsemen may ride in tandem: last December, in The Atlantic, in “The College Essay is Dead,” Stephen Marche chastised humanists for “committing soft suicide” by mostly ignoring technological change for decades.

Heller makes only parenthetical reference to institutions, like the University of California, Berkeley, that have seen rising enrollments in humanities. Yet the trend is undeniable—humanities enrollments have been declining for years, and there is no evidence of an overall rebound. So how might English adapt, belatedly, to end-times?

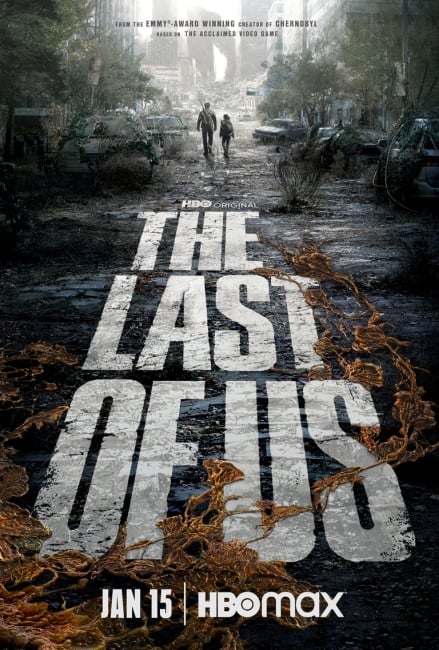

Forget about the Harvard University professor Stephen Greenblatt’s suggestion that English departments would do well to turn their attention to long-form television. In a mocumentary-like interview with Heller, Greenblatt—described as “one of the highest-ranking humanities professors by the stripes and badges of the trade”—toyed with Silly Putty while he counted off hit series: “The Wire, Breaking Bad, Chernobyl—there are dozens of these now!’” To this list, he might have added HBO’s current hit: the postapocalyptic The Last of Us captures the current mood of English departments, which see one prospective student after another infected by the STEM and business bugs. So does Station Eleven, where a small group of remnants cling wishfully to Shakespeare. So does The Handmaid’s Tale, which depicts a nation afflicted by ideological conservatism and infertility. Aging English faculties, like the one depicted in Netflix’s The Chair, have the dismal sense that there is no next generation. My own department resembles a backgammon board in which every single piece has crossed the midpoint and several have started bearing off into retirement.

Yet reading critically—as English majors are trained to do—Heller’s assessment offers not only a basis for hope, but a forward-thinking vision for humanities departments and especially for English. Here, I want to lend more specificity to two familiar arguments for supporting humanities education, one philosophical and the other career-oriented. On the one hand, there is the traditional notion that the humanities cultivate empathetic, critical-thinking citizens (one of Heller’s interviewees, the Columbia University professor James Shapiro, claimed that the decline of the humanities tracks with the decline of democracy). On the other hand, advocates such as Humanities Works point out that employers, even or especially in STEM fields and business, value the sort of creative, adaptive, nuanced thinking and communication skills fostered by humanities.

As Heller suggests, the self-congratulatory belief in humanities education as “cultivation of the mind” has been largely faith-based: “This model describes one of those pursuits, like acupuncture or psychoanalysis, which seem to produce salutary effects through mechanisms that we have tried but basically failed to explain.” But Heller is wrong about acupuncture, if not psychoanalysis—there is scientific research into its mechanisms of action. Similarly, Heller is neglecting research into the interactions between literature and the human brain.

As the neuroscientist Maryanne Wolf demonstrates in Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World (HarperCollins, 2018) literacy education, beginning in early childhood, involves the brain’s neuroplasticity. In a sense, the reading brain is a sort of artificial intelligence, because literacy, unlike language, is not innate. It doesn’t depend on existing “circuits”; it shapes new ones. Their most elaborate capacity is for the sort of deep reading occasioned by literature: characterized by contemplative, associative thought, empathetic connections and insights. She writes, “The expansive, encompassing processes that underlie insight and reflection in the present reading brain represent our best complement and antidote to the cognitive and emotional changes that are the sequelae of the multiple, life-enhancing achievements of a digital age.” In other words, as our absorption in digital media has affected our cognitive development, literature provides a necessary counterbalance.

For literature instructors at all levels, the science Wolf presents about the “reading brain” should be deeply validating: it’s an empirical basis for the miracle that we all implicitly believe in. And for citizens more broadly, this science exploring how digital technology affects the reading brain—our capacities for analytical and reflective thinking, for sustained attention (or “cognitive patience”), for empathy and perspective-taking—should be concerning. Literary study is important now precisely because the sort of cognition it fosters and sustains is so endangered. Even Shapiro, an extremely late smartphone adopter, admitted to Heller that “‘Technology in the last 20 years has changed all of us,’” including him. He used to read five novels a month; now he tries to fit in one. Similarly, Wolf tried a small experiment on herself, re-reading Herman Hesse’s Magister Ludi, a favorite novel from her youth, and found that she could not sustain her attention. I’ve had the same experience. Like many English professors, I’m sure, I think back to a youth in which I read nearly constantly, and I’m pained to recognize that I’ve lost the stamina. Inspired by Wolf’s vision of the reading brain, I’m getting back to analog texts, and I feel like I’m slowly recovering the experience of deep reading, a practice that used to be second nature.

An implication of this neuroscience is that literature departments should keep doing what we do best. It’s not a question of whether literature is relevant: it’s relevant because of what we do with it and vice versa. Our chief contribution can’t be a by-product—“communication skills!”—that other programs of study develop more directly. Instead, by teaching literature, we’re fostering a way of thinking that is exciting and often arduous and that students can’t get anywhere else.

Especially not from artificial intelligence. As Heller writes, “ChatGPT can no more conceive Mrs. Dalloway than it can guide and people-manage an organization. Instead, A.I. can gather and order information, design experiments and processes, produce descriptive writing and mediocre craftwork and compose basic code and those are the careers likeliest to go into slow eclipse.”

“I think the future belongs to the humanities,” Sanjay Sarma, a professor of mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told Heller.

If that’s the case, then we need more English majors and minors and faculty (!) to help build that future. And we shouldn’t do so by dwelling on the past, but rather by engaging with the new media landscape, including AI, and demonstrating the fundamental role of literature within it.