You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

So you almost have that book contract in your grasp. You’ve had your most trusted colleagues drop a favorable hint about your work in the ear of the acquisitions editor at the best press in your field. You carefully (and, of course, unobtrusively) stalked said editor at the spring meeting of your disciplinary society, and managed to “accidentally” meet at the drinks reception.

You wrote a follow-up e-mail — not too soon, not too late — with a general query describing your idea and how it fits into the broader publication program at Desirable University Press. And when you received back that warm response — O, happy day! — you observed a decent interval before sending off your polished proposal, on which, of course, you’ve been working ceaselessly for the last six months.

And now you’re refreshing your inbox every five minutes or so, waiting for that hoped-for green light.

Did you ever think — after all your work — that what you were producing was a luxury?

Probably not. All you really want is for the best publisher, whatever that means to you, to publish it; and for your ideas to receive notice in the reviews that matter in your field. Well, you’d probably like your promotion and tenure committee to be impressed, too. Royalties would be nice, but more than anything, you want impact.

Yet maybe you think it should be a luxury, after all the effort and sweat and heartache you’ve invested in it. As far as you’re concerned, it’s pure gold, and should be priced accordingly. You can be sure it will. According to one book provider for university libraries, the average cover price of an academic book now stands at around $90.00 — a few multiples more than the average price of a book.

It’s not just the price that makes scholarly books a luxury. Think about this line from a recent study of luxury goods: “In luxury, quality is assumed, price does not have to be explained rationally; it is the price of the intangibles (history, legend, prestige of the brand)."

That sounds a lot like the system of scholarly publishing we have come to know and love (and/or loathe). It’s exactly the history, legend, prestige of the brand — the welter of such elements as the name of a given press, the backlist of titles in its catalog, the reputation of the institution with which it is (to a greater or lesser degree) affiliated, the grand old stories we tell about the way a certain editor championed a book against a sea of troubles — that gives the whole enterprise a whiff of mystique and nobility. Scholarly publishing, like any other luxury good, is a reputation-driven business producing goods for a select few at high prices, which in turn transmit a signal about the value of the good — and the prestige of the producer.

But as any social psychologist can tell you, reputations are a bad shortcut to reality. On the contrary, they can be a fruitful source of bias — filled with meaning we make instead of content we assess.

If you think about it, it’s surprising that scholarly publishing is — and seemingly should be — a business in which brand reputation is not just operative, but essential. Stories abound of promotion and tenure committees advising candidates of the four or five publishers with which a book they present must be placed — at least if they have hopes of further advancement. But of course to say this is to mistake the brand for the content. After all, scholarly merit is supposed to be a function of, well, merit, not mere reputation. Isn’t it? Aren’t we supposed to read the books, and not merely the spine?

• • •

The old chestnut that academic publishing is in a state of crisis may or may not be true; that all depends on your definition of “crisis.” What is certainly true is that the nature of scholarly publishing has changed, in some ways so much that it would scarcely be recognizable to the founding generation of university press directors.

After all, it is only meaningful to distinguish “scholarly publishing” from all other sorts of publishing if it has not just a distinctive content but a distinctive purpose.

The content is indisputably meant to be scholarly work of great merit. Even within a single field disagreements may (and do) arise about exactly what merit is, but no one seriously disputes that the content provided by academic presses is, or ought to be, characterized by a kind of defensible and substantive merit.

That is to say, scholarly publishing — at least in the days American university presses were established — was seen as a way for scholars to communicate their ideas with each other in ways that would not depend, at least not critically, on the market. Exactly because the market would be a poor judge of scholarly merit, producing scholarly work was seen as an extension of institutional mission. Colleges and universities exist not merely to create, but to communicate knowledge; and the social privileges conferred because of that mission (notably, qualification to receive charitable gifts incentivized by the tax code) entail social responsibilities to support both the process and the production of research.

So here’s a thesis. If there truly is a crisis in scholarly publishing, it has arisen from this fundamental first cause: the end of the era in which institutions sponsoring presses saw the publishing of scholarship as something near to the heart of their core mission, and deserving to be supported on those terms. Result: What was never intended to be a system left to the vicissitudes of the market has become exactly that. Scholarly books have become high-priced, prestige-driven luxury goods not by accident, but by forgetfulness.

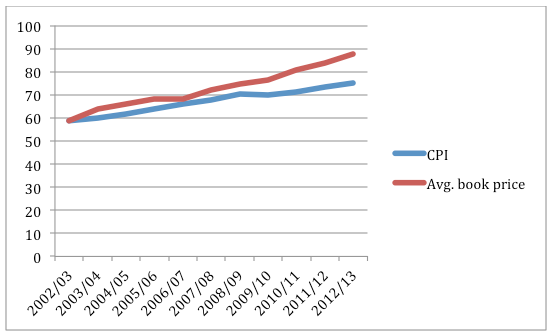

Symptoms of this shift abound. Presses unable to break even are closed, or severely curtailed, as universities refocus on “strategic priorities." Book prices rise at a rate far higher than inflation in order to cover publishers’ fixed costs as institutional subventions vanish. Authors are chosen not so much on the basis of prize-winning, promising early work but rather because they can command the services of a literary agent.

It doesn’t have to be this way. To solve the crisis we should speak frankly of its causes, and imagine alternatives to received structures. There are three points to keep in view as we invent and test alternatives.

• Open access doesn’t mean poor quality. The push for open access, an idea received with acute suspicion in some quarters, has come about in no small way as a direct consequence of the predictable failure of a market-based system for scholarly publishing to serve its audience.

As a species we are pretty hardwired to associate cost with value — one reason why luxury goods, for which no rational explanation can suffice, yet exist. That is the hardest challenge for open-access advocates (of which I am one) to overcome; how can something free be trusted? But there is no logical connection between the price (as distinguished from the production cost) of a scholarly work and its merit. Yes, assuring quality is a costly business. But there are other ways of paying those costs than depending on purchase-price revenue.

• Communicating ideas is (or should be) critical to the mission of all institutions. The relationship between publishing and the institutional mission needs to be reassessed. Real and lasting change in the broken system of scholarly communication cannot be accomplished by publishers, or libraries, alone. Ultimately it will take a critical mass of institutional leaders able to see how abandoning academic presses to the market was, in effect, abdicating a core scholarly responsibility. I am fortunate to work in an institution led by such people, with the result that the revenue on which we will do the expected work of assuring quality and publishing scholarship will be borne by institutional commitments instead of consumers.

• Disruptive innovation is messy. Changing the revenue model — shifting the source of the revenue from either end of the value chain (purchases by consumers at one end, or “author fees” at the other) to institutional commitments at the center — is made possible by new technologies for distribution (digital publishing). But will also mean the emergence of a new set of ideas for the kinds of institutions that do scholarly publishing.

For one thing, there may well be a larger number of publishers producing a smaller number of works on a focused set of topics. Most of the proposed solutions to the “crisis,” both those offered by publishers and those sponsored by foundations, have been essentially focused on preserving the current demographic profile of university presses. It is not self-evident that this is the only solution. Liberal arts colleges (to cite my own example) have a valuable and distinct contribution to make to the identification of what constitutes “scholarship” — but, with a few admirable exceptions, have been frozen out of the conversation by the sheer volume of production required by a market-dependent system. That can now change.

So, too, digital tools make possible not only different ways of producing work, but different ways of organizing the work of publishers. University presses, by and large, are organized as hierarchical firms — and with good reason; such organizations manage market pressures efficiently. But academic publishing could become much more like a commons, adapting to its own purposes Yochai Benkler’s ideas of commons-based peer production in which the uniting thread is a shared passion for the development and distribution of new ideas among colleagues and peers. Said in different terms, what if the future of academic publishing looked less like the Encyclopædia Britannica, and more like Wikipedia?

Good luck on the book contract. When you get it — and, of course, you will — remember why you got into your field in the first place. It probably wasn’t to produce luxuries, but to create ideas and communicate them to your peers — the same reason I wrote this piece. So when you have an idea for your next book, think about working with a publisher who shares those goals.