You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

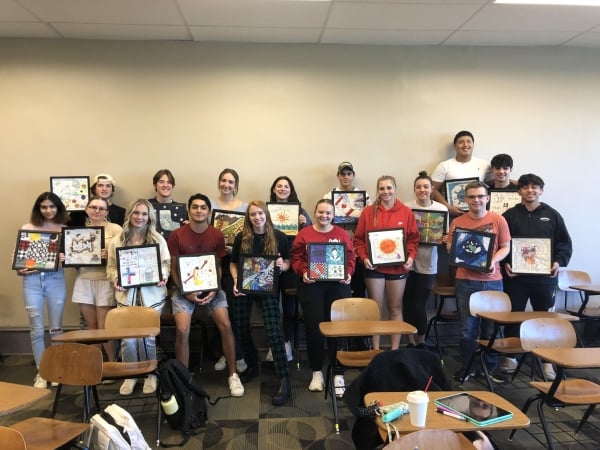

An autobiographical quilt square created by one of the author’s first-year seminar students.

Courtesy of Laura Skandera Trombley

My 18 students stare at their sewing needles as if I have just handed them a 19th-century divining rod. They are enrolled in my first-year seminar, Autobiography in the Age of the Selfie, and on the first day, when I asked them why they had chosen this topic, their responses ranged from “it fit into my schedule” to “I like to read” and “my mom told me to take a class with the president.”

This seminar, teaching first-semester first-year students, has always been my favorite class. This is my opportunity to teach some beloved literary content, to reassure new students all will be well and to introduce skills they will need to be successful in college. I am deeply engaged with this course, and with each offering I aim to push the boundaries far beyond what students expect or have previously experienced in class.

I keep experimenting, to keep me on my toes, but, more importantly, to reawaken students to just how interesting and fun (in a very academic sense) learning is. Too often by the time our overachieving students land at my university, they resemble exhausted salary workers who have put in long hours in high school doing everything they rightfully think is required to be admitted to a highly selective liberal arts university. In other words, they have had a job for the past four years that too many of them did not find particularly enjoyable. I see it as my responsibility to demonstrate that their next four years will be transformative.

The way Southwestern University’s first-year seminar program is structured is both inventive and strategic. Our incoming students begin the seminar a week before the rest of their scheduled courses; in their first week, classes run four consecutive days, for periods alternating between two and three hours. This schedule demands innovative pedagogy to hold students’ interest and presents an opportunity for them to form the first of their campus friend groups. Also, a real bonus for students is that the first-year seminar program ends before the rest of their classes, typically by the end of October, meaning they have a lighter load the last weeks of the semester.

My syllabus consists of a mixture of texts, films, an off-campus trip, poetry memorization, dance instruction and what I’ll call other projects. I warn students there are heavy reading assignments, including Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Walden, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, The Year of Magical Thinking and a few excerpts from Mark Twain’s Autobiography (I’m a Twain scholar and look for every opportunity to infuse a bit of Clemens into my teaching).

During the first week, we have two activities that are foundational to the course. First, we all watch Christopher Nolan’s 2014 film, Interstellar, starring Matthew McConaughey, where students are introduced to the course’s themes of truth, identity and time. Shortly after the film was released, I met Nobel Prize recipient Kip Thorne, who served as the film’s science adviser and became a friend. While he was proud that actual physics was embedded throughout the movie, he emphasized that it was all about love across time and space; he encouraged me to watch it again (and again).

The film is relatively long and complicated (all that real science), and I love watching my students’ expressions as the credits roll, from trying to figure out “how does a space film fit into the genre of autobiography and memoir” to rubbing away the tears brought on by the father-and- daughter scene and wondering why Matt Damon’s character is so angry. “All will be revealed,” I tell them, and you will be the ones to figure it out.

Because Southwestern emphasizes the concept of paideia—bringing together perspectives from different fields to help students build their critical thinking skills and expand their ways of knowing—I invite faculty from different disciplines to give their interpretations of time. A physics professor discusses its representation as a physical dimension and, just for fun, provides a brilliant explanation of the theory of relativity (immediately after he exited the classroom, one of my students told me he wanted to be a physics major). A music professor and conductor talks about Hans Zimmer’s soundtrack and how his subtle alteration of the time signature of the waltz underscores the quest for new worlds. My students are amazed by this contextual information.

At the end of the first week, I hand out needles and thread. I start with my supposition that humans have always evidenced a strong desire to leave a record of their existence and that autobiographies and memoirs represent only a fraction of what humans have made in that regard over the ages. I ask for examples, and my students volunteer cave paintings, poems, pyramids and songs. All fine, I agree, and I then introduce another means of expression that occupies a definitional gray area.

Quilting, defined both as a handicraft as well as an art form, has traditionally been a vehicle of expression for those who are poor, illiterate and female. Students read Kathleen Spivack’s “The Moments-of-Past-Happiness Quilt” and Alice Walker’s “Everyday Use.” A student reads a quotation to the class that I hand him: “After all, a woman didn’t leave much behind in the world to show she’d been there. Even the children she bore and raised got their father’s name. But her quilts, now that was something she could pass on” (Sandra Dallas).

The time has arrived, I announce, for everyone to create their own autobiographical quilt square. My students gape in disbelief. I am fortunate to have as my co-instructor a staff member who is an expert quilter, and she shares some of her gorgeous autobiographical quilts. My students examine her work, awestruck. Rather taken aback, we discover that not one of my students has ever sewn two pieces of cloth together or, for that matter, held a sewing needle. They panic and are convinced that I have given them an impossible task. They anxiously ask what they are supposed to do to satisfy this requirement. I tell them to create a square that represents their life, and they can sew, paint, draw, glue anything they desire. This open-endedness overwhelms them, and they suspect that somehow there is a downside to my encouraging their creativity. Before class is over that day, we all take the first step in the process, and everyone has learned how to thread a needle.

Over the course of the next several weeks, the last 15 minutes of the 75-minute class session is devoted to quilting. Students sit in a circle, helping each other with their design, untangling knots, talking about their reading and writing assignments, and encouraging each other.

My co-instructor and I provide much positive affirmation, and it soon becomes apparent that this is my students’ favorite time. They begin telling me they’ve figured out why I have given them this assignment, that I’m trying to demonstrate quilting is like composing an essay; that while mistakes will be made, they can always be edited and redone; and that quality takes time. I smile and agree, saying they have me all figured out. They share that when they feel stressed at night, they will take out their quilting ring and start sewing that the act of stitching calms them. They confide with pride that students in the residence halls don’t know how to quilt, but they do. I ask them to think about the audience for their square, and they say mothers, fathers and grandparents.

Courtesy of Laura Skandera Trombley

At the end of the fall semester, there is a first-year research symposium, and I announce that we will be participating. Each of their 17 squares has been framed and set up on a long table. Some of my students tear up, because they never thought they could create anything so personal and beautiful. I ask everyone to squeeze together for a picture that I will post on my Insta. They laugh and smile proudly. Curious students, staff and faculty members walk over to converse with them. My students, now all quilters and writers, tell their audience about the autobiographies they’ve read and their favorite writers, about the meaning of Interstellar, the process of quilting and why the course’s themes make sense to them now. Paideia is no longer just a concept but a means of understanding their existence.

In the spring semester, I run into a few of my former pupils, who volunteer to come visit the class when I teach it next year. They explain to me that it would be helpful if they talked to new students about how to take a class with me and to reassure them that in the beginning it might not make sense, but it will come together in unexpected ways. I thank them, decide to take them up on their generous offer and start planning for next time.