You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Interview by Okla Elliott

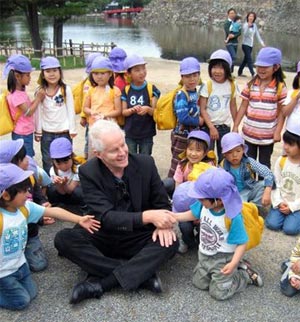

David Kirby teaches English at Florida State University. He has received many honors for his work, including fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, and his work appears frequently in the Best American Poetry and Pushcart Prize volumes. Kirby is the author of numerous books, including The House on Boulevard St.: New and Selected Poems, which was a finalist for the 2007 National Book Award in poetry. His Little Richard: The Birth of Rock ‘n’ Roll was named one of Booklist’s Top 10 Black History Non-Fiction Books of 2010, and the Times Literary Supplement called it “a hymn of praise to the emancipatory power of nonsense.” Kirby’s latest poetry collection is Talking About Movies With Jesus. The following interview was conducted via email between September and November, 2011.

David Kirby teaches English at Florida State University. He has received many honors for his work, including fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, and his work appears frequently in the Best American Poetry and Pushcart Prize volumes. Kirby is the author of numerous books, including The House on Boulevard St.: New and Selected Poems, which was a finalist for the 2007 National Book Award in poetry. His Little Richard: The Birth of Rock ‘n’ Roll was named one of Booklist’s Top 10 Black History Non-Fiction Books of 2010, and the Times Literary Supplement called it “a hymn of praise to the emancipatory power of nonsense.” Kirby’s latest poetry collection is Talking About Movies With Jesus. The following interview was conducted via email between September and November, 2011.

***

Okla Elliott: It has always bothered me that journals differentiate between prose fiction and prose nonfiction, but poetry gets no such distinction. Many of your poems feel like memoir-in-verse or creative nonfiction-in-verse, since you name yourself, your wife, friends, books you’ve written, travels you’ve done, and so forth. Could you talk about your poetic persona and its relation to the fiction/nonfiction divide? Also, why do you think we largely fail to make this distinction for poetry but are often vehement about it for prose?

David Kirby: People sometimes say to me, “Did that really happen?” And it hurts my feelings. As in, what, you can’t tell? It’s not that what I’m describing is outlandish. Or if it is, I think you can tell when I cross the line. All poem beginnings, mine and those of others, are small. So when I meet my upstairs neighbor in “The Search for Baby Combover,” for example, that’s plausible, right? There’s nothing odd about meeting your neighbor. But later in the poem, when Barbara and I adopt a baby that’s really a pillowcase with knots for ears and a face drawn with a marker, okay, I’m making that part up. As far as my rationale for writing first-person poetry, I like what Borges says: “I am ashamed to have spoken of my own personal case—except for the fact that people always hope for confessions and I have no reason to deny them mine.”

Borges is touching on a key point about audiences, which is that we tend to insist that poetry be autobiographical. Probably that’s true because, to most people, poetry is what you write when you’re lonely, mad at your boyfriend, and so on. Editors don’t classify poetry the way they do prose because it’s less easy to tell the difference between what happened and what didn’t in poetry. And I must say, I appreciate the tags “fiction” and “essays” in magazines; it makes a difference how I read. Maybe I should have a disclaimer at the beginning of each of my poems that’s the opposite of the one you see in the movies. This one will say, “All characters in this poem are real, and every action in it actually occurred.” And that’s the truth. After all, I didn’t adopt a pillowcase baby, but I imagined that I did, and isn’t that an action as real as any? Isn’t thinking a thought as startling and noisy as throwing a brick through a window?

OE: Your new book, Talking about Movies with Jesus, makes use of pop-culture references to films and music (as does previous work of yours), and you’ve written a book on Little Richard. What is the interplay between the so-called fine arts and pop-culture in your work? Are these even meaningful distinctions, or are they arbitrarily determined?

OE: Your new book, Talking about Movies with Jesus, makes use of pop-culture references to films and music (as does previous work of yours), and you’ve written a book on Little Richard. What is the interplay between the so-called fine arts and pop-culture in your work? Are these even meaningful distinctions, or are they arbitrarily determined?

DK: When I do Q&A after a reading, there are several questions I can usually count on. The first is “I notice you write about Europe a lot—why?” For the next three, instead of “Europe,” I get “your wife,” “humor,” and “music.” I take this to mean the questioner doesn’t write about these things in his or her poetry and, indeed, has probably never run into any poems about Europe, my wife, humor, or music. The tone of these questions is almost always benign, though sometimes the “why?” can sound a little pointed, and in that case, I’m guessing that the person is not asking a question at all but making a statement along the lines of “Look, buddy, either write the way everybody else does or quit calling yourself a poet.”

So, yeah, obviously some people make a distinction between pop culture and the fine arts. Not me, though. I mean, I can tell the difference, but I’m pretty democratic about these things. My latest crush is on a Russian writer named Varlam Shalamov, who says, “Every word is a piece of the world.” How can someone say this or that is not a worthy subject? There are a lot of poets who’ve made fabulous careers out of what Mark Halliday calls Holy Hush poetry, which is where you see something and describe it and say the world is sacred. Don’t we know that already, though? And there are actually many poems of this kind that are very good, but to insist your students write exactly the same kind of poem that you do seems stifling to me.

By the way, I usually don’t say all this when someone poses one of those why-do-you-write-the-way-you-do questions. I just wait for a beat and say, “Well, I don’t know . . . people seem to like it.”

OE: Moving away from aesthetic questions and over to practical ones, I wonder what your thoughts are on the publishing world today as opposed to, say, twenty-eight years ago when your first collection of poems came out. How has the proliferation of literary journals and small presses, online publishers, e-books, and so affected the landscape? Which aspects are better today and which aspects worse, as you see it?

DK: Old-school magazine editors are my heroes; it’s such hard work, and surely the rewards are few. These beautiful issues show up in my mail box all the time, and I look at them with admiration as well as a kind of premature nostalgia, because every one is really a book of sorts, a big thick anthology of smart poems and essays and stories and photos and art work.

I’m the lowest-tech guy you know—I’m still impressed by the little machines that dispense toothpicks next to restaurant cash registers. So I wouldn’t know, but I have to think online journals are easier to wrangle. For that reason among several others, print journals are more prestigious and will be for a while, though that seems to be changing. Best of all, of course, is the journal that’s published in both print and electronic formats; those are the ones to aim for when you send stuff out.

And even though I’m the low-tech guy, I bought an e-reader last year so I wouldn’t have to carry a sack of books with me everywhere I go. I went to Russia this summer for thirty-two days; can you imagine carrying the books you’d want to read for a trip like that? I ended up bringing three or four hundred books, all in a little gadget that weighs about as much as half a sandwich.

I bought my e-reader at Borders, by the way, which just went bankrupt and closed all its stores because not enough people are buying print books now. So like you and everybody else, Okla, I’m part of the solution and part of the problem, too. That’ll never change.

OE: One trend I’ve noticed in contemporary American literature is the general avoidance of politics (with a handful of exceptions of course). You have occasionally taken political material and used it in your poems -- sometimes for simultaneously humorous and serious purposes. I am thinking of “Skinny-Dipping with Pat Nixon” from your newest collection, Talking about Movies with Jesus. The poem’s title already announces itself as both political and playful. Would you talk a bit about how you think the political and the literary intertwine in general, and perhaps more specifically in this poem (and others of yours)?

DK: Labeling something “politics” is like labeling it “philosophy.” Sure, you can reduce everything to politics or philosophy or whatever you like. But the key word here is the verb “reduce,” because what you’re doing is taking something complex and making it small. As a reader or a writer, you should never dummy anything down. I’ve had people say my writing isn’t political enough, but I’ve also had people tell my writing isn’t Christian enough. I mean, come on.

All poems have small beginnings, and mine does, too. The first few stanzas of “Skinny-Dipping with Pat Nixon” deal with politics, but that’s just a prologue to a larger drama. I always thought that Pat Nixon was one of those people who got in over her head. She was trapped, in other words. We’re always being told that we can be what we want to be if we just put our minds to it, but probably the majority of the people in the world are trapped in a situation they’d give anything to get out of. What makes her case poignant is that Pat Nixon was trapped at the very highest level. Just pull up any image of her—you can see it in her face. So I wanted to free her, make her sexy, and show her a good time, at least for one night.

And I write about politics all the time; it’s just that I don’t do it in poetry. Why bother? Most poets are Communist peace creeps like me anyway; why preach to the converted? If I want to sound off on an issue, I’ll write an editorial for a newspaper, not a villanelle. Also, as of this evening, I have 3,463 friends on Facebook, so if I feel like debating some contemporary issue (which I do at least twice a day), I’m assured of getting lots of comeback that way. Then I’m free to sneak off and go swimming with the wives of former U.S. presidents.

And I write about politics all the time; it’s just that I don’t do it in poetry. Why bother? Most poets are Communist peace creeps like me anyway; why preach to the converted? If I want to sound off on an issue, I’ll write an editorial for a newspaper, not a villanelle. Also, as of this evening, I have 3,463 friends on Facebook, so if I feel like debating some contemporary issue (which I do at least twice a day), I’m assured of getting lots of comeback that way. Then I’m free to sneak off and go swimming with the wives of former U.S. presidents.

OE: What new projects are you working on? And would you discuss how you discovered or decided on these projects? Writers get random ideas all the time. How do you determine which are worth pursuing and which are better off buried behind the barn?

DK: My projects are like Soviet space shots. I don’t say anything until the rocket lifts off, and if it blows up on the launching pad, you’ll never hear about it. So I’m reluctant to get specific, but I will describe some general projects; after all, I assume you want to know more about how a writer’s mind works than what book is coming out in 2014.

First of all, there are two books of poetry I have in mind. The first is a sort of greatest hits collection, which is not the same as a selected or collected poems; the latter is a gathering of representative poetry, whereas what I have in mind are the poems people like most, the ones they email me about or ask for at readings. The second book would consist of poems that are—how shall I say this?—a bit hairy-legged, perhaps. Some of these are poems that editors have asked me to take out of manuscripts because they’re too transgressive. Others are ones that I never dared to put into a manuscript but strike me as worthy now. This book would be a bit sulfurous, a little warm to the touch. I probably wouldn’t take this to my regular press; I’d find somebody who’s a bit daring.

Then I’m working on two books of what might be called poetics or pedagogy. These are prose works; each is a collection of short blips from a single sentence to several paragraphs in length. The first is an examination of indistinctness. We’re always told to be concrete, right? Yet a lot of literature takes its strength from the hasty utterance—the broad brushstroke, as it were. And the second is a similarly organized blip anthology, although these blips deal with everything I’ve learned about poetry from a lifetime of writing and teaching the stuff. Here’s a sample for you: “Art is the deliberate transformed by the accidental.” That’s all that’s on that one page. So these two books consist largely of Zen-style koans, little sayings for the reader to think on and, if we’re all lucky, learn from.

Then I’m working on two books of what might be called poetics or pedagogy. These are prose works; each is a collection of short blips from a single sentence to several paragraphs in length. The first is an examination of indistinctness. We’re always told to be concrete, right? Yet a lot of literature takes its strength from the hasty utterance—the broad brushstroke, as it were. And the second is a similarly organized blip anthology, although these blips deal with everything I’ve learned about poetry from a lifetime of writing and teaching the stuff. Here’s a sample for you: “Art is the deliberate transformed by the accidental.” That’s all that’s on that one page. So these two books consist largely of Zen-style koans, little sayings for the reader to think on and, if we’re all lucky, learn from.

I’m working on a book on pop music, too, and specifically on the role of audiences. You know I'm a music writer? Of course, poetry pays the bills at my house, and after several books and some favorable notices, I began to get feelers from editors asking me to write pieces of various kinds on the poetry business. Which I did and cheerfully, for years, until I felt the need for change and reinvented myself as a music journalist; eventually I published a book on Little Richard. And I started taking guitar lessons, figuring that if I wanted to bring more to my music writing than a fan’s enthusiasm, I’d better find out about things like double stops and walkdowns.

Anyway, those are a few book projects I have in mind, any or all of which are liable to merge, bifurcate, or morph into something completely different. And that’s just books. Every year I publish thirty or forty short pieces, be they articles, reviews, poems, or liner notes. And most of this is by request. The phone doesn’t ring every day; some days it’ll ring ten times, and then six months will go by in total silence. But sooner or later, the phone rings.