You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The College Board canceled more AP test scores than normal this year after results were compromised by an international cash-for-questions operation.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | joebelanger and Dilok Klaisataporn/iStock/Getty Images

Last week, high school students around the world received an email telling them their Advanced Placement exam scores were under review for potential academic integrity violations—and, if corroborated, they could be canceled.

Many students thought it was a phishing scam at first. In incredulous Reddit posts and panicked Tik Tok comments, they questioned the legitimacy of the email’s domain and fretted about how the message might impact their college acceptances.

But on July 8, when AP results were released, it became clear the initial emails were not fake: students received a follow-up message saying their scores, across a variety of subject areas, were canceled. While the College Board, which owns and administers the AP subject tests, declined to cite the specific number of cancellations this year, the organization confirmed that it was higher than normal.

“We have canceled more AP Exams than usual after identifying students who participated in unethical conduct,” Holly Stepp, the College Board’s executive director of media relations, wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed. She added that “the total number remains a fraction of 1 percent of exams.”

The “unethical conduct” was a leak of test materials in May that made its way onto the international black market. Those materials managed to reach an unusually large number of students this year in a globe-spanning cash-for-questions operation—though Stepp said that “none of the materials were so widely shared that we needed to cancel entire exam subjects or scores from whole countries.”

Still, the security compromise was significant enough that the College Board is re-evaluating its timeline for digitizing the AP exams, which it hopes will make them less vulnerable to leaks and other traditional modes of cheating.

“Based on these challenges, we are reexamining the delivery of our exams to thwart theft and cheating and thereby avoid more widespread cancellations in the future,” Stepp wrote. “Digitally administered AP Exams are much more secure than shipping paper exams in boxes to thousands of locations weeks in advance.”

A Technological ‘Arms Race’

Christian Moriarty, professor of ethics and law at St. Petersburg College in Florida, where he chairs the Applied Ethics Institute, said that in recent years a combination of technological developments, the internationalization of the assessment industry and heightened competition in selective college admissions have exacerbated a perennial problem for high-stakes exams like the AP.

“Cheating has always been around and more rife than most people probably realize, since the days when people wrote answers on their arms,” he said. “Over the years, though, this kind of cheating”—accessing test materials before the exam—“has become much more common and much easier to get away with.”

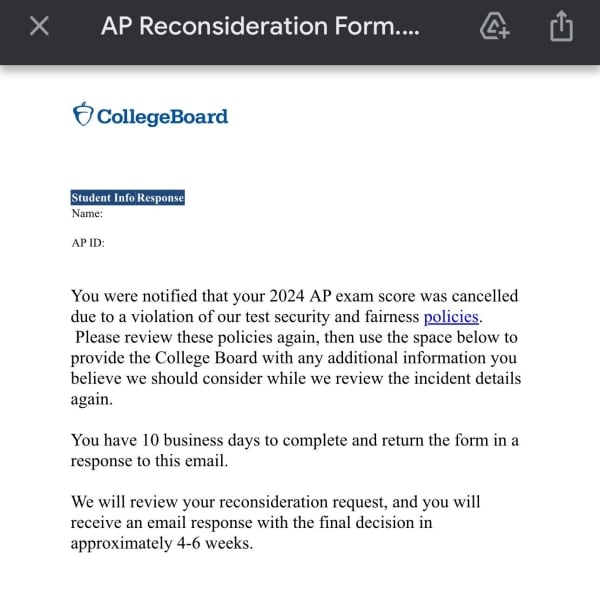

An email informing a student that their AP test scores were under review for possible cancellation, confirmed as legitimate to Inside Higher Ed by the College Board.

The means of cheating are changing as the tests themselves change. This past March the College Board introduced its new, completely digital SAT, which the nonprofit says is more secure due to its adaptive nature: students receive different questions later in the test depending on how well they do early on. After the latest security compromise, Stepp wrote that the College Board is looking to “accelerate our current road map” to do the same for AP tests.

Whether that will significantly reduce the likelihood of similar cheating tactics in the future is unclear. Timothy Gallen, director of college counseling at the Solebury School in New Hope, Pennsylvania, said that in his experience, paper tests weren't the issue this year.

“The irony is that the one student in my school who has had a score withheld for security reasons had taken a digital exam,” he wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed. “None of our paper testers have had their scores withheld.”

Steve Addicott, chief operating officer of the nearly 20-year-old assessment-security firm Caveon, said that while “truly adaptive” digital tests are typically more secure than static paper ones, new threats have evolved alongside the new technology, including the proxy test-taker market, which boomed during the pandemic.

“Bad actors are leveraging technology the same way assessment companies are,” Addicott said. “It’s an arms race.”

A Sea of ‘Test Pirates’

While students’ use of leaked materials was more widespread than usual this year, these operations are not uncommon. Addicott called it a “huge industry.”

“Nearly all high-stakes testing organizations are dealing not just with cheaters but with rings of test pirates, who are not trying to increase their scores but harvesting items illegally to sell online so that other people can gain unfair advantage,” he said. “It’s these groups that are incredibly sophisticated, organized, and make bundles of money … They’re parasites.”

Addicott said the cheating rings primarily work in one of three ways. In some cases there’s a leak on the inside, from a test writer or proctor, who funnels answer sheets to an outside criminal group. In others, he said, the enterprises employ a kind of secret agent to take an early test, equipped with recording tools that sound like something out of a James Bond movie—“high-definition cameras built into glasses, buttons, jewelry … contact lenses”—and sell the pictures. The third and most common type uses multiple student test takers, each of whom memorizes a small portion of the test and reports back their assigned questions, recreating a complete test that they can then distribute to eager buyers.

This year’s big AP leak appears to have originated on encrypted social media channels in China, including Xian Yu and Taobao, but students in classrooms across the U.S. also reported on social media that their scores had been canceled. Many of them proclaimed their innocence. Rob Lamb, a high school counselor at the Sage Ridge School in Reno, Nev., said that while he hadn’t heard of any of his students receiving the cancellation email, they’d been tittering about the possibility since hearing news of the exam leaks in China in May.

Stepp said the College Board takes pains to ensure its anticheating measures don’t inhibit “access to our exams for the vast majority of students who play by the rules.” Addicott said that while there are ways to do that—“dishonest test takers leave a trail of breadcrumbs”—it’s not always easy.

Moriarty compared the increasingly strict security net to the Transportation Security Administration after the Sept. 11 attacks: “security theater” that can be frustrating for many but is ultimately an effective deterrent.

“Anytime you increase security, you inevitably are going to have a gradient effect where students who didn’t cheat get caught in the crosshairs,” he said. “But you also need to maintain trust in these exams or they have no value to any student … It’s a hard balance to strike.”

(This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Steve Addicott's name.)