You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

“Incorrect.” Halfway through the practice quiz, I get a question wrong. I matched two terms to the wrong examples, and the quiz tells me they should be swapped. “Do you know why?” it asks.

I don’t, and the course doesn't tell me. But the quiz will soon give me the same question, which I can then answer simply from memory.

For the past two weeks, I have worked my way through Principles of Marketing, a course offered by JumpCourse, an online education platform created by adaptive learning company Adapt Courseware.

After approaching the course as I would any other course -- reading, taking notes, quizzing myself -- I opted for a brute-force strategy. Instead of reading the lecture notes or, when available, watching the video lectures, I started skipping directly to the practice quiz.

Through inferring the correct answers, lucky guesswork, and trial and error, I completed 40 of the course’s roughly 240 units. I have a perfect score in all but two. I have never taken a course or worked in marketing.

If I keep this up and pass a proctored multiple-choice exam, I can take my results to the American Council on Education, which recommends colleges should grant me three credit hours toward a degree.

Inside Higher Ed agreed to test JumpCourse after Daniel F. Sullivan, a sociologist and president emeritus of St. Lawrence University, completed JumpCourse’s Introduction to Sociology course and passed a proctored exam.

Sullivan (at right), also a former president of Allegheny College and faculty member and administrator at Carleton College, shared his concerns in an op-ed. The course, he writes, contained “unclear or contradictory” definitions and distinctions that “didn’t seem sensible,” and didn’t challenge him “to think through any complex problems or to use any quantitative reasoning skills.” Although he said the final exam was structured better, he ultimately felt as though the course amounted to “CliffsNotes for credit.”

In follow-up interviews, Sullivan said the course left him “stunned” by the lack of quality. JumpCourse stressed its courses have been independently evaluated. ACE, which has approved the courses for credit recommendation, won’t share the standards it uses to review courses.

The case highlights the larger debate about the role of introductory courses and the skills they should impart to students. It is also case of conflicting expectations: Should a $149 self-paced fully online course be directly compared to a traditional face-to-face course, even though both can award credit?

Alternative Providers and Unbundling

JumpCourse, like StraighterLine and other alternative or nontraditional providers, sprang up outside the boundaries of traditional higher education. For entrepreneurs, the incentives are clear: if, as some critics say, academe moves too slowly to tackle the issues of how to make higher education more accessible and affordable, then moving outside that structure creates opportunities to experiment without maneuvering through federal regulations, accrediting standards, shared governance and institutional review boards.

Inside Higher Ed explores alternative providers:

In other words, alternative providers offer courses without being accredited or awarding credit, and learners aren’t eligible for federal financial aid. Some providers award only certificates or badges, but others have had their courses approved for credit recommendation -- a process in which an organization reviews the course and vouches for its quality. Colleges then decide if they will accept the recommendation and award credit.

The call to bring alternative providers into the fold of higher education has grown more vocal in the past year.

Presidential candidates across the political spectrum have endorsed the idea. In her higher education plan, former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton proposed using federal funds as “a lever to ensure accreditors are open to low-cost, technology-enabled programs,” but noted that the programs should be “rigorously evaluate[d].” Florida Senator Marco Rubio took a more confrontational position in a policy speech, promising to “bust this [accreditation] cartel by establishing a new accreditation process that welcomes low-cost, innovative providers.”

The idea also has support within the Obama administration. The U.S. Department of Education is considering an “experimental sites” project in which certain colleges and alternative providers would work together to offer financial aid-eligible programs. More details are expected in the coming weeks.

An expansion of federal financial aid to alternative providers would help enable a concept known as unbundling, in which students would combine smaller modules of education -- for example, massive open online courses and programs offered by coding academies -- into degrees, bypassing general education as traditionally offered.

The Association of American Colleges and Universities, for which Sullivan is a senior adviser, has struck a cautious tone about unbundling. In an interview Sullivan, who stressed that he was speaking for himself and not on behalf of AAC&U, amplified his criticism, comparing alternative providers to the use of human subjects in research.

Sullivan collected examples of lecture notes and practice questions from the sociology courses -- and his comments on them -- in a document. In a section on the women's movement, for example, the lecture notes state, “The first wave of feminism began at the end of the 19th century and continued into the 20th century.” As Sullivan points out, the notes do not mention the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, a pivotal event in the early days of the movement.

“When you’re experimenting with new technologies to build something cheaper or to provide a service in a cheaper way, you’re not experimenting with future lives of the people who you’re testing these innovations on,” Sullivan said. “People are essentially asking the government to accredit way before we understand the risks and benefits of this kind of stuff and to allow corporations to entice unsuspecting naïve people into thinking this is actually going to be a benefit, and it’s not going to be a cost.”

Faculty Tested, ACE Approved

Mark Brodsky, CEO of Adapt Courseware, defended JumpCourse and its course offerings, but said he welcomed constructive criticism. While not everyone may agree with its approach or methodology, he said, the company has received mostly positive feedback since JumpCourse introduced its first five courses in May 2014.

“Dan [Sullivan] is not the first person to say this in an academic setting,” Brodsky said. “Academics that we’ve had review our courseware … are definitely much more critical than students are. To be honest, I don’t know when some of that is really constructive criticism or almost a fear that this type of thing that’s going to replace the traditional role of faculty members teaching this course.”

Brodsky compared the course design process to how a publisher creates a textbook. On its website, JumpCourse writes, “While we can’t tell you all of our little secrets, we can say that each JumpCourse is created by instructional designers, writers, video producers, professional storytellers, subject matter experts, and otherwise passionate and talented individuals who want to help expand access and affordability of college education.”

The subject matter experts “typically have advanced degrees in their field,” and the courses are peer-reviewed by other academics before launch, Brodsky said.

In addition to faculty members reviewing the courses, JumpCourse has conducted “hundreds” of focus groups and paid learners to take the courses to the end. The results have been “stellar,” with JumpCourse learners more likely than the average learner to pass standardized tests that award college credit in areas where they have existing experience or knowledge, said Rebecca Ferraro, director of client services.

“We’ve done our own window shopping and comparison,” Brodsky added. “We know the quality of the content that we put in our courses is absolutely unmatched.”

Adapt Courseware can also point to support from outside organizations such as ACE, which has recommended its courses -- including Introduction to Sociology and Principles of Marketing and nine others -- for credit.

To be approved for credit recommendation, each course had to be reviewed by a faculty committee, said Deborah Seymour, assistant vice president for ACE’s Center for Education Attainment and Innovation. The reviewers, who represent all sectors of higher education and are trained by ACE, are tasked with reviewing the courses’ assessments and outcomes and how they compare to equivalent college courses, Seymour said.

“The process that they use is a rigorous one,” Seymour said. “There are a number of courses that don’t achieve the credit recommendation, and it’s not the case that every time we send a faculty team to look at a course, it’s automatically branded yes.”

When reviewing online courses such as the ones offered by JumpCourse, faculty are expected to go through the entire course. As a general guideline, reviewers should “stick to our standards around teaching quality and assessment,” Seymour said. But those standards are “proprietary” and not available to the public, she said.

JumpCourse has also promoted its connection to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (see above), writing in its About section that it has “been recognized by the [foundation] for adaptive learning.” After being notified of that language by Inside Higher Ed, however, a Gates spokesperson said the foundation was “perplexed” and would ask JumpCourse to remove the claim from the website, which the company later did.

“This idea that they would market as recognized by us is inaccurate,” the spokesperson said. “It’s really kind of misleading.”

The foundation in October 2013 awarded North Carolina State University a $100,000 grant through its Adaptive Learning Market Acceleration Program. The university chose to work with Adapt Courseware on a psychology course. JumpCourse wouldn’t launch its first courses for another seven months.

The JumpCourse Experience

At the beginning of Principles of Marketing, learners are greeted with the following introduction:

“As you will soon see, this course is different from anything you have experienced before. You'll have a lot more choice in how you learn, and a lot more real-time feedback about how you are doing. Because you are in control, you learn more efficiently, retain more of what you learn and have more fun learning. The course responds to you, providing learning activities keyed to your level of understanding. We call it adaptive learning.”

JumpCourse now offers 11 introductory courses in disciplines such as math, American government and psychology. Each course is divided into several sections, and each section is further broken down into modules known as units. In Principles of Marketing, a single unit may contain a page of lectures notes on product research with definitions of key terms, a five-minute video and a dozen practice questions.

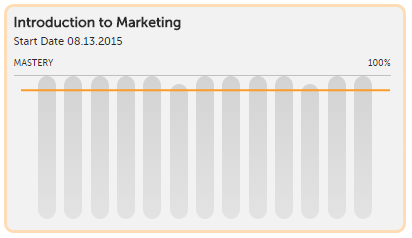

Learners have three attempts to answer each practice question correctly. A correct answer on the first attempt fills a part of the mastery bar, which must be filled to at least 90 percent to unlock the next unit.

That method of completing a course is “highlighting a strength and not a flaw,” Brodsky said. How learners decide to interact with the content depends on their motivation, he said. Some may prefer to watch the video lecture, others read the lecture notes, and others yet dive into the practice section. “We’re not trying to prescribe learnings to meet certain learning styles, but we are allowing for students to learn the best way they learn,” he said.

Sullivan questioned whether those three methods of taking a course sufficiently prepares students for college-level studies. “The implication is that watching, reading and practicing -- and here they mean answering practice questions -- represent the varieties of ways people learn,” he wrote. “But aren’t engage, write, debate, analyze, critique, research, encounter, participate and other activities also ways of learning that might be best for a given student?”

JumpCourse plans to review and refresh the courses on a regular basis, Brodsky said, and newer courses include more ways of evaluating learners. In Foundations of Reading & Writing, for example, students are required to submit samples of their writing (though that course has not yet been approved for credit recommendation by ACE). Other courses include case studies or require students to participate in the forums, he said.

Sullivan also challenged the notion that the courses should be considered adaptive, a claim he called “narrow and vacuous.”

Some companies define adaptive learning as technology that sends learners on personalized paths through content, suggesting new resources if learners get stuck. For JumpCourse, the adaptive part happens during the assessment. The course, the company says, “slows down or speeds up the delivery of the material depending on your pace of learning.”

Practically speaking, this means the practice section will reproduce questions from units where the learner scored lower than 100 percent -- for example, asking a question about the history of marketing philosophies in a practice section on Internet marketing. It will also occasionally ask review questions. Answering questions from previously completed units correctly bumps the mastery score in that section up to a perfect 100.

The Role of Introductory Courses

Brodsky said JumpCourse’s goal is to “augment” higher education, not “replace” it. He said he hoped students who pay several hundred dollars a credit hour “get a heck of a lot more” from their courses compared to what JumpCourse offers for $149.

Adapt Courseware originally built its courses with two concepts in mind, Brodsky said. First, the courses should be flexible enough to be used in a supplementary role, for example, as content students could consume on their own time in a flipped course that combines face-to-face and online instruction. Second, the courses should prepare learners to pass standardized tests such as the College Level Examination Program (CLEP) exam, offered by the College Board.

A preparatory version of the courses costs $99, but learners have to sign up for one of the standardized tests on their own. The $149 ACE-approved version includes a proctored exam. For another $40, learners who pass the exam can register to receive “one transcript, data housing, technical support and advocacy on behalf of the student” from ACE.

“There’s a healthy debate in academe about what an introductory course should be, and I don’t think we set out to try to change that paradigm,” Brodsky said. “If you take our Introduction to Psychology course, is it preparing you to be a major in psychology? I’d probably go as far as to say no, not necessarily. Are they designed for a student to get college credit? That is for sure the case. Is it designed for them to be able to … complete a higher-level course? I think to some extent for sure, but I’m not sure if we thought about it in that exact context.”

Organizations such as AAC&U, in comparison, have focused on importance of communication, rigor, writing and subject-matter learning in introductory courses. The AAC&U has for more than a decade has been engaged in Liberal Education and America’s Promise (LEAP), a campaign to promote liberal education. The campaign argues introductory courses help students “acquire the broad knowledge, higher order capacities and real-world experience they need to thrive both in the economy and in a globally engaged democracy.”

“What JumpCourse says about introductory courses is that they’re really not intended to lead students to higher learning,” Sullivan said. “They’re treated as an occasion to learn the names and dates and basic concepts, and not as a place to start students on the path of developing their critically important liberal education skills. … As an aspiration for introductory students, that’s dishearteningly low relative to where college graduates have to be by the end [of their studies].”

JumpCourse and others have taken a more pragmatic approach. The Gates Foundation, for example, has been a strong promoter of the “college completion agenda,” spending hundreds of millions of dollars on initiatives intended to help more students graduate and join the workforce. Many of those efforts have targeted introductory courses, which traditionally have had high dropout and failure rates.

The ACE Alternative Credit Project, one such initiative, ties the Gates Foundation, JumpCourse and ACE together. The foundation in August 2014 awarded ACE a $2.1 million grant to review alternative providers and “promote greater acceptance of alternative credit.”

JumpCourse applied to and was accepted into the program, which means its courses will once again be evaluated. The quality assessment rubric is available online. ACE hopes to begin publishing results this fall, Seymour said.

Brodsky remained confident that the courses will still be recommended for credit.

“Look, I don’t think anyone who’s in online learning will say that -- for all learners -- an online course is the best experience when there’s clear evidence that hybrid courses and classroom-based courses still offer a lot of value to a lot of students for a lot of reasons,” Brodsky said. “We offer this as a way for people who are trying to finish their college education who have the challenges of a lot of adult learners in an alternative way and at a much lower cost.”