You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

In their investigation into a vandalism incident, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill police requested a search warrant for data on a student organization they think might have been involved.

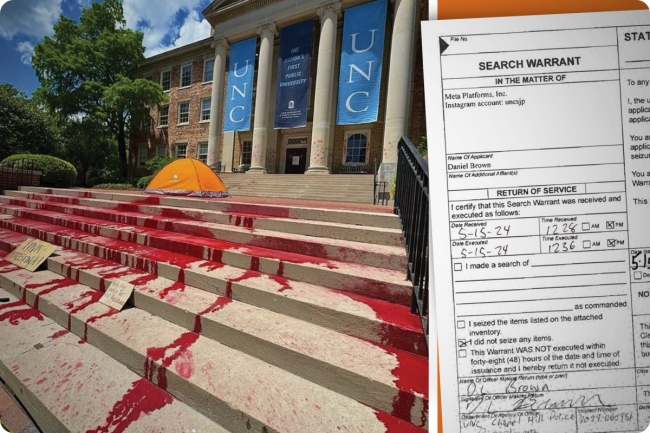

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | UNC Students for Justice in Palestine | Orange District Court

As part of its investigation into vandalism that occurred on campus in May, the police department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is searching for clues in the Instagram account of UNC Students for Justice in Palestine.

The department obtained a search warrant for the account’s data, including the name and address of its owner, direct messages sent and received, location data, and more, according to the warrant. Meta, the company that owns both Instagram and Facebook, is responsible for providing the police with that information.

It’s the latest attempt by university administrators to punish students for crimes like vandalism, trespassing and destruction of property that took place during pro-Palestinian protests in the spring. While a number of university and local police departments have dropped charges against protesters—often at the request of the university president—UNC’s is one of a relatively small number of campus police forces moving forward with criminal charges.

“No one has the right to disrupt campus operations, threaten or harass others, shut down a speaker, or destroy public property,” interim chancellor Lee Roberts said during a Board of Trustees meeting shortly after the vandalism incident, according to public radio station WUNC. “Now that commencement is over, information collected during recent events is being reviewed to pursue potential violations of policies and applicable laws.”

The move to secure social media data is another indication that the university does not intend to let protesters off easily, according to one expert who noted that obtaining such data is often a relatively long and arduous process for investigators.

In the affidavit supporting the warrant, UNC police investigator Daniel Brown outlined why the police need the data to investigate the May 11 vandalism of UNC’s South Building, where a group of protesters splattered red paint on the sidewalk before smearing it across the building’s exterior walls and windows. The vandalism, he explained, took place the same day as an event advertised by the UNC SJP on Instagram: the People’s Graduation, a celebration for protesters who had faced disciplinary action and thus couldn’t graduate as planned. The post instructed attendees to “wear bloc,” or cover their faces and notable features to avoid being identified. After the event, the account posted photos of the defaced building.

“Your affiant believes that the individual or individuals running the uncsjp Instagram account planned and or participated in the damage that was caused on 05/11/24,” Brown wrote in the affidavit. “They have used their account to post a flyer of the event as well as tactics to obscure law enforcement efforts to identify those that would cause property damage and posted a picture of the damage that was caused from their event.”

UNC’s SJP, like many similar organizations at universities across the country, maintains a frequently updated Instagram presence, posting statements about the ongoing Israel-Hamas war, publicizing upcoming protest events and sharing pictures and videos from those events.

In a statement posted on the account, the group denied involvement in the red paint incident.

“While UNC SJP had no role in facilitating these autonomous actions, we nevertheless reiterate our support for direct actions aimed at undermining support for occupation, apartheid, and genocide. We agree with the autonomous activists: UNC has blood on its hands,” the post read.

It criticized the warrant as an attempt to “silence, harass, and repress SJP and any student committed [to] Palestinian liberation.”

Zachary Greenberg, a senior program officer at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, said his organization has reached out to UNC and the student group and is investigating the incident. He fears the warrant was requested in response to protected student speech.

“There are definitely free speech concerns here. Merely showing pictures of crime or praising crime or commenting on it is protected expression,” he said. “We have the right to talk about these political issues, and the mere act of posting about it and praising it is protected.”

He also noted that it is unclear whether the warrant was UNCPD’s first attempt to obtain information about the individuals who vandalized the South Building, stressing that they first should have tried simply to speak with the club members.

“It’s a pretty rare sight for a search warrant [to be requested], considering that this is a registered student organization. They have a point of contact with the university and the university can simply ask the group for the information that the police are requesting under the search warrant,” he said. (Although the group is indeed a registered student organization, it was suspended on May 1, according to a UNC SJP Instagram post.)

An Uncommon Strategy

According to Farhang Heydari, an assistant professor of law at Vanderbilt University who studies policing technologies, such warrants are common in criminal investigations; Meta reported that in 2023, it fielded over 147,355 requests for user data from the government and law enforcement agencies and provided the information in over 88 percent of cases. But Heydari noted that it’s somewhat rare for warrants to be used in an investigation into a relatively minor crime like vandalism.

“Putting together a warrant, going to a judge, getting approval, getting in touch with a company—that takes a lot of time,” he said. “It is hard to imagine that any police would go through all this for ordinary vandalism. But these are campus police, so they have less crime to deal with, and campus police usually have to answer to the leadership of the university.”

Sophia Brown, a spokesperson for UNC SJP, noted that the group also has been told by their legal counsel that it is unusual for law enforcement to request a warrant for an organization like theirs; typically such warrants are issued for an individual suspected of being connected to a crime.

Inside Higher Ed reached out to several other university police departments to see if they were using social media in ongoing investigations related to campus protests; most did not respond or declined to comment, but a spokesperson for the University of Wisconsin at Madison’s police department said they have used some public social media posts to help investigate crimes allegedly committed while police dismantled a pro-Palestinian encampment.

“We did not use social media to help identify people. All of the individuals who we cited were arrested that day—and that’s when they were identified. We did use some open-source social media to document behaviors in some instances, but social media was not used for identification purposes,” Marc Lovicott, a spokesperson for the department, wrote in an email.

Using social media to identify protesters and find evidence of crimes committed during protests has become an increasingly common police strategy in recent years, especially during high-profile protests like the Black Lives Matter actions in 2020. Even so, social media continues to be a powerful tool for organizing activists on campuses and beyond. It’s unclear whether UNC’s strategy will be adopted by other institutions investigating student protesters and, if so, whether that will impact how such groups use social media going forward.

“The search warrant asks for essentially all the info about the social media account … so, these search warrants can be chilling because of the burden of complying with this request and the potential release of this private information to a government actor,” Greenberg said.