You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Pexels.com

Female academics’ research productivity dropped off at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak, which many experts have attributed to women’s outsize role in caregiving even before the pandemic. Some also blame women’s disproportionate service roles and take-up of emotional labor.

Months later, journal submission rates for women have improved in some cases. But the general outlook for women remains poor, with K-12 schools still closed in many communities, childcare options and other services still greatly reduced, and a bumpy teaching semester ahead.

Watching, Waiting on Preprints

“We are seeing some recent improvements, though I worry that those will drop precipitously as the semester begins,” Cassidy Sugimoto, professor of informatics at Indiana University at Bloomington and a co-author of an ongoing study of article submissions to preprint databases, said as her own two daughters did their remote schoolwork in the next room. “Issues such as disproportionate teaching and service obligations, coupled with the move to online schooling for children, are likely to take a toll on women in the upcoming year.”

Sugimoto and her co-authors published their initial COVID-19-era preprint analysis in Nature Index in May.

“We are all in the same storm, but not in the same boat,” they wrote at the time. “The scientific workforce has moved en masse into the home, where male faculty are four times more likely to have a partner engaged in full domestic care than their female colleagues.”

That analysis looked at submissions to 11 preprint repositories, which are indicative of overall research activity, and three platforms for registered reports, which are indicative of new projects. Sugimoto and her colleagues found that women submitted fewer articles in March and April 2020 compared to the preceding two months and to March and April 2019. Submissions by women as first, or primary, authors -- often junior scholars -- were especially down, with some indication that they were shifting to middle authors.

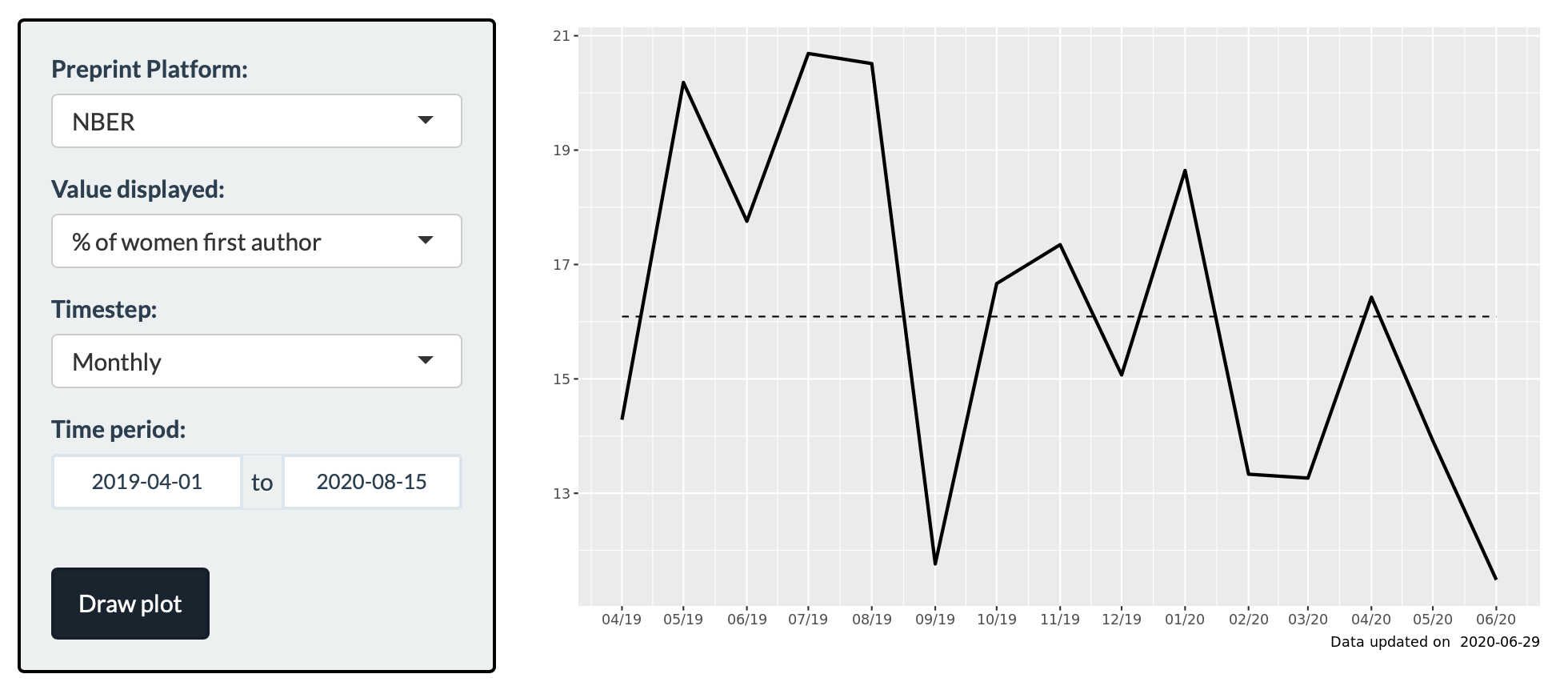

EarthArXiv, medRxiv, SocArXiv and National Bureau of Economic Research working papers saw the biggest declines in female authorship. In arXiv and bioRxiv, female authorship had been increasing in January and February 2020 but then dropped as COVID-19 spread, to match rates in earlier years.

Female first-author submissions to medRxiv, a medical preprint site, dropped from 36 percent in December to 20 percent in April, for example. In addition to potentially harming the careers of the junior scholars who often take on first-author roles, Sugimoto and her colleagues wrote that the medical first-authorship gap has public health implications. Why? If much of the current medical research is on COVID-19, and if “women and other minorities are absent,” it may “alter the emphasis on aspects of the virus that are particularly important for certain populations.” Indeed, other researchers have found that COVID-19-related papers in medicine and economics have fewer female authors than expected. In economics in particular, it is senior, male academics who are publishing on these new issues.

Sugimoto and her colleagues continue to track preprint submission rates for women. The most recent available data, from June and July, show some normalization of women’s submission rates. Regarding medRxiv, for instance, female first authorship dropped to about 16 percent in April. It has been climbing back toward the year average of about 31 percent since. Some areas have yet to improve, though. Female first-author submissions to NBER, for economics research, were still around 11 percent in June, compared to about 18 percent in June 2019 and the 16 percent year average.

Sugimoto and her colleagues have argued that the clearest way to track women’s productivity rates is via preprints, as these prepublished papers reveal what academics are submitting, not just what is getting green-lit after the formal peer-review process. Other researchers have said the same, with similar findings. Some individual journal editors similarly concerned about gender equity in publishing during COVID-19 also have shared their own submission data and analyses.

From the Mouths of Editors

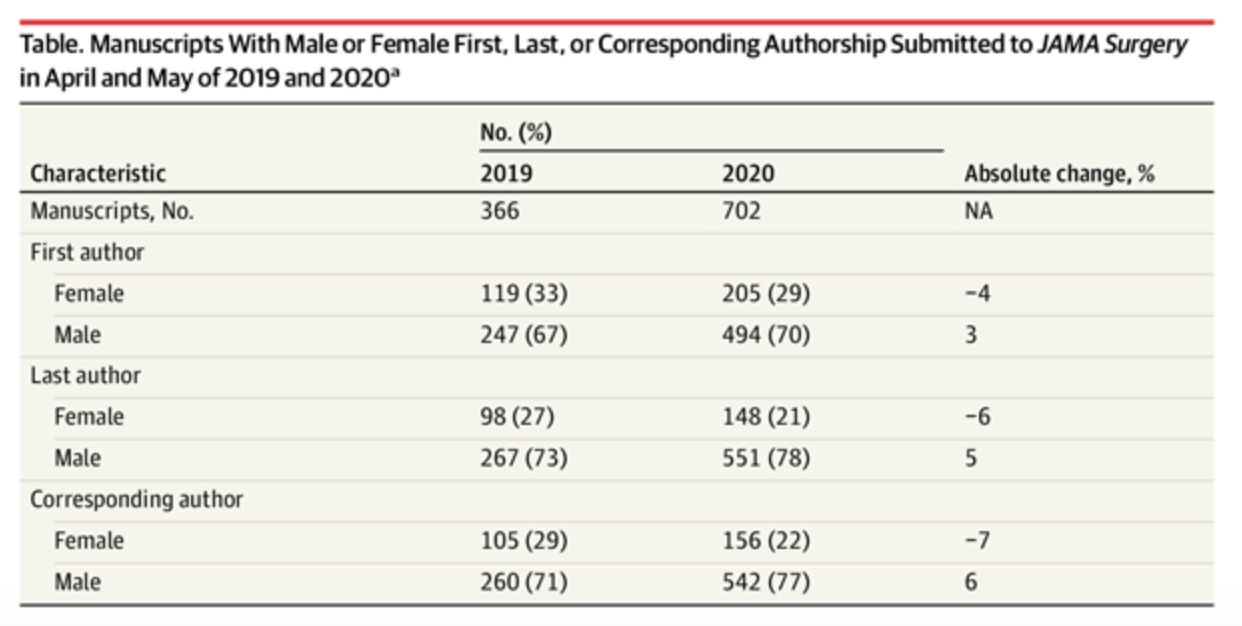

The earliest journal-specific analyses parallel the preprint findings: that women are being squeezed out of their reading and research time. Some newer analyses reveal similar patterns. An editorial published this month in JAMA Surgery said that April and May submissions to the journal saw a 4 percent decline in female first-author submissions compared to a year earlier, and a 3 percent increase in male first authors. Last, often senior, author submissions by women deceased 6 percent over the same period, and men’s senior author submissions rose 5 percent. The pattern was the same for corresponding authors. Men are winning the COVID-19 publishing game and women are losing out.

Melina R. Kibbe, editor of JAMA Surgery, and Colin G. Thomas Jr., MD Distinguished Professor and Chair in surgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, warned in the piece that “increased responsibility of childcare on female parents may also lead to greater work-related burnout among women.” It’s already a problem, she said but with pandemic “increasing this burden, women may be at a greater risk of leaving their academic medical careers.”

Melina R. Kibbe, editor of JAMA Surgery, and Colin G. Thomas Jr., MD Distinguished Professor and Chair in surgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, warned in the piece that “increased responsibility of childcare on female parents may also lead to greater work-related burnout among women.” It’s already a problem, she said but with pandemic “increasing this burden, women may be at a greater risk of leaving their academic medical careers.”

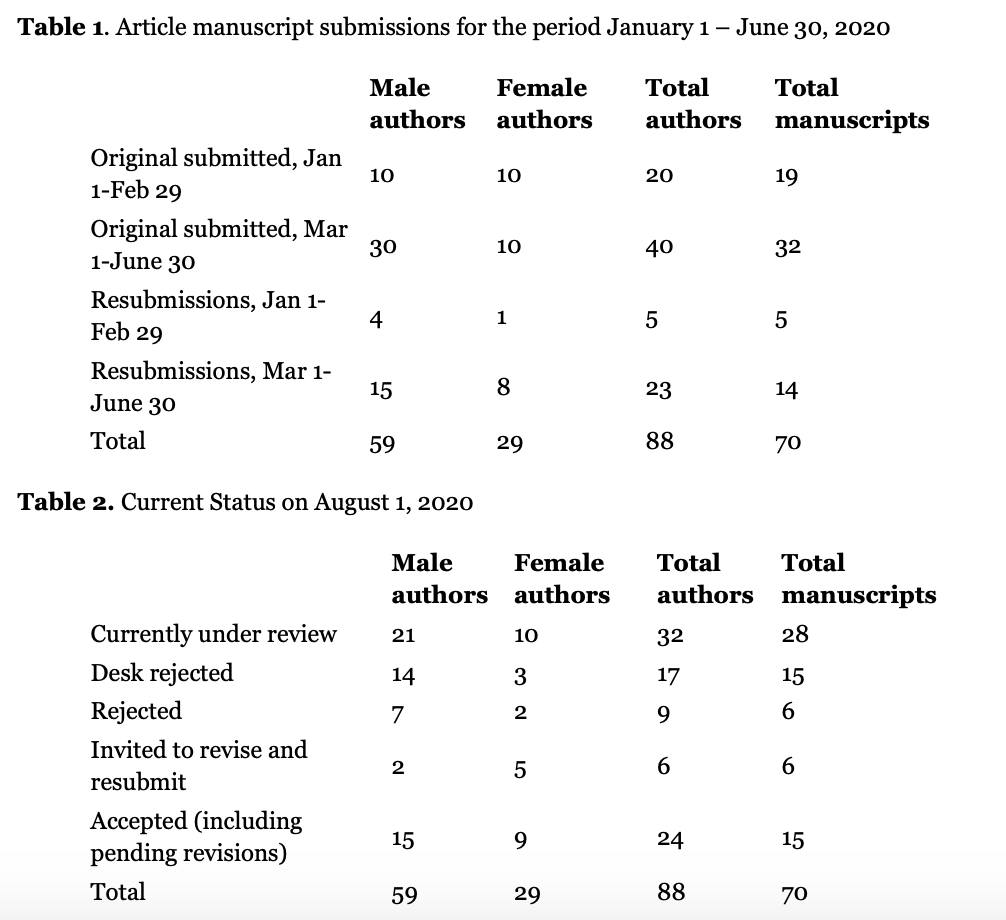

Isis, a journal of the History of Science Society, ran its own numbers and found that female and male authors submitted original papers in equal numbers in January and February. After that, through June 30, male authors outnumbered female authors by more than three to one. As of Aug. 1, the journal had 32 authors under review: 21 male and 10 female. Most manuscripts are single authored. Invited contributions have been less affected.

“We can add our own anecdotal experience to these numbers,” Isis’s editors wrote. “Many of the people whose work is required to produce an issue of Isis -- that is to say, referees, book reviewers and invited contributors as well as manuscript authors -- have declined invitations or asked us to extend deadlines explicitly as a result of the pandemic. Of those specifically citing childcare responsibilities, the overwhelming majority were women.”

Beyond that, they said, "We can’t offer specific insights about the underlying reasons for the gender skew the pandemic seems to have generated within our ambit. We can only offer our general sense that the consensus view is correct that such a thing is happening, that it is exacerbating the existing structural inequalities, and intersecting with race- and class-based marginalization."

The Isis editors were even more cautious in their analysis, saying that they represent a relatively small journal that will consider a maximum of 800 submissions over five years. They also expressed discomfort with how they’d conducted their analysis, assuming authors’ gender by their names. Even so, they thought it was important to draw their contributors and readers into a data-based conversation about how they -- and the greater History of Science Society -- might best respond to these dynamics. The group is planning a series of virtual towns halls for later this year.

Amanda Murdie, Thomas P. and M. Jean Lauth Public Affairs Professor at the University of Georgia and editor in chief of International Studies Review, published an analysis of publication rates with other editors of International Studies Association journals earlier this year. Overall submissions were up since COVID-19, but the share of submissions submitted by women was down. Murdie said Wednesday there are “a lot of reasons to assume that things have gotten worse as time has gone on, especially for women, but that is just a conjecture at this point.”

What’s clear, from an editorial standpoint, “is that it is taking our reviewers much longer to submit reviews,” but Murdie didn’t have a gender breakdown for that.

“It’s also taking us longer to find the necessary number of reviewers for manuscripts,” she added. “Many scholars that would have previously agreed to review are turning us down, often apologetically, with reference to COVID and work-life struggles.” All of that lengthens the timeline for publishing decisions, which could be add to junior scholars’ research concerns, in particular.

Internationally, some journals report being similarly affected. Among academics in Brazil -- and to Isis's point on marginalization -- Black mothers report particular strain, according to one study. The Canadian Journal of Political Science reported informally that women consistently represented about 30 percent of first authors over the past three years. Submissions in April and May were similar, and women represented 33 percent of first authors on accepted pieces. But Brenda O’Neill, co-editor and a professor of political science at the University of Calgary, said on Twitter that this time period also coincided with a request for short papers on COVID-19.

O’Neill said this week that the COVID-19 series “was unusual in that the pieces were very short and had an extremely rapid turnaround. This might have made a difference.” Asked how to measure women’s contributions through the lens of political science’s particular authorship norms -- authors often list their names alphabetically -- O’Neill said the field moves authors with heavier duties to the front of the list when necessary. (Of course, she said, “If the authors with heaviest duties have a surname that starts with a letter lower down in the alphabetic than the other authors, you can’t know how the duties were, so it’s a weird practice.”)

While the pandemic publishing conversation is getting longer on data and is about to get longer (the coronavirus isn’t going anywhere and, apparently, neither are the kids and other dependents), it’s thus far short on solutions.

Overdue Conversations

As a department head, Murdie said she’s “hopeful that universities can be more creative and flexible when it comes to tenure clocks and the effects of the pandemic. Any changes need to consider the increased service and teaching commitments some individuals faced during the pandemic, as well as inequalities in research access.”

Kibbe, of JAMA Surgery, said in her editorial that even as no immediate solution is available, “It would behoove academic institutions, funding agencies and societies to recognize this increased burden on female parents and develop processes to try to alleviate these pressures.”

Creative and out-of-the box solutions require “diverse and innovative thinking,” she added. Allowances for part-time work and different work shifts should be available to those who need them, and agencies should extend grant end dates and allow for increased funding carryover from year to year.

Kibbe, among many other advocates of carers within academe, also recommends pausing tenure clocks during the pandemic. But that already widely adopted intervention has its critics, who say that it’s not enough and can even hurt women and other minoritized faculty members in that it delays their career progression in an number of ways and decreases their lifetime earnings.

Sugimoto, of Indiana, said she’s “particularly concerned about pausing the tenure clock” because it effectively “takes those who are in vulnerable positions in academe and extends that period of vulnerability.” Plus, she said, the “implicit assumption at some institutions will be that these faculty need to work even harder in this extra year to demonstrate their worth.”

Instead of “extending periods of vulnerability and demanding additional labor at lower compensation,” Sugimoto said that institutions should change not their timelines but their “evaluative structure, to take into account the unique constraints of our time.”

Megan Frederickson, an associate professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Toronto who published her own preprint analysis in May and has another one in the works, said recently that things aren’t going to be normal for parents for a long time. Case in point: her young son was supposed to attend day camp this week but had to prove that he didn’t have coronavirus in order to return after a one-day tummy ache (he’s fine). In that light, Frederickson said she wished she knew of ways that institutions have helped normalize things, beyond tenure-clock extensions (she doesn't).

Frederickson noted that her colleagues in public health at Toronto published an open letter to administrators, asking them to "recognize, and act to redress, the disproportionate gendered burden of home schooling/daycare, and of elder care responsibilities, for employees working at home." The University of California, Los Angeles, and other institutions received similar faculty missives.

Frederickson said she guessed that universities are generally “so overwhelmed trying to figure out what they will do about online versus in-person instruction, student residences, international student visas and so on, that they simply don’t have the bandwidth or budget to address the massive childcare challenge faced by many of their faculty and staff -- not to mention some students.”

But it’s “frustrating to feel like, once again, childcare and the needs of working mothers are taking a back seat to other concerns, many of which are valid and urgent, to be sure.”

Dessie Clark, research collaboration coordinator for the ADVANCE program at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and co-author of a forthcoming paper on institutional responses to COVID-19, said that if universities “are committed to diversity, they have to create new ways of assessing faculty productivity. It’s important to consider both structural changes, like adding impact statements to personnel files, and cultural changes that center conversations around equity.”

Kate Power, a research consultant who has written about women’s disproportionate caring loads during the pandemic, said she was only able to write her recent article because the journal editor was “extremely supportive,” giving feedback on two drafts before submission and otherwise flexible. Power suggested that colleagues in research institutions may be able to support each other in similar ways, even when journal editors can’t. She also encouraged carers who have any room in their schedules to write to look for co-authors or lead authors.

Academic departments, meanwhile, can help redistribute work so that those with additional caring responsibilities aren’t expected to do the same amount of work that “doesn’t count” like research does, Power said. She compared the pandemic to other times when carers may request accommodations, such as parental leave.

In any case, Power said, the challenge “needs more thinking about and a bigger public conversation, because this situation is not going away fast.”

That conversation is long overdue, she added, in that “women and carers are supposed to just fit into a system designed for people without caring responsibilities. There is a saying working mothers have: ‘You have to work like you don’t have children and parent like you don’t have a job.’ And that was before COVID-19.”

Alexandra Hui, associate professor of history at Mississippi State University and co-editor of Isis, also said she hoped that this public health crisis would lead to significant “shifts” in academe, perhaps concerning childcare options, support for faculty and staff parents, and both institutional and disciplinary tenure standards.

“That change isn’t going to happen fast enough for people right now,” Hui cautioned. But “I don’t think we’re going to retreat to the very narrow representations” of women in academe seen 100 years ago.

For Hui, at least, this time has already “normalized” the scholar-parent identity to some degree.

“On Zoom meetings, I, for one, let my child wander into the frame. Yes, he’s my child, and he’s here because no one else can watch him.”