You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

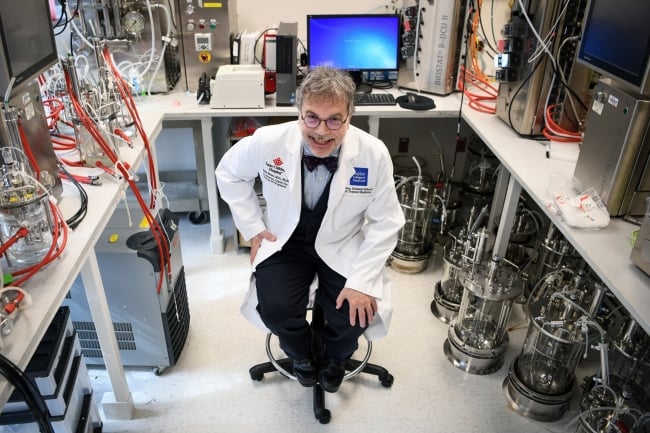

Dr. Peter Hotez has spent his career developing low-cost vaccines for the world’s poorest people.

Agapito Sanchez/Baylor College of Medicine

Dr. Peter Hotez knows vaccines. He co-directs the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development. He’s a professor of pediatrics and molecular virology at Baylor College of Medicine. And he’s dean of that institution’s National School of Tropical Medicine.

Hotez also knows Robert F. Kennedy Jr., President-elect Donald Trump’s nominee for health and human services secretary.

Long before Trump announced his pick, Hotez publicly criticized Kennedy for his debunked claims about vaccines. In 2020, Hotez published a book titled Vaccines Did Not Cause Rachel’s Autism about his adult daughter.

Hotez and other academics have publicly raised alarm about Kennedy’s nomination to lead the Department of Health and Human Services and the agencies that compose it. Kennedy has said he plans to immediately replace 600 employees at the National Institutes of Health and tell its scientists, “We’re going to give infectious disease a break for about eight years,” other news outlets have reported.

Hotez stopped by Washington, D.C., last weekend to accept an award from the scientific research honor society Sigma Xi. During his speech, he recounted his team’s development of low-cost vaccines, including COVID-19 shots for 100 million people in India and Indonesia, and spoke about backlash he’s received for publicly defending vaccines. Inside Higher Ed sat down with him after his speech to talk about his research, his reaction to Kennedy’s nomination and ways to reduce vaccine skepticism in the future.

The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Q: Could you please summarize what you’ve done during your career to develop and promote vaccines, including COVID-19 vaccines?

A: I’ve devoted my life to developing low-cost vaccines for neglected diseases, for people who live in extreme poverty, the vaccines that the big pharma companies won’t make … But then, at the same time, we developed low-cost coronavirus vaccines, including a low-cost COVID vaccine that reached 100 million people … The other side of what I do is I defend vaccines against rising antivaccine activism.

Q: So let’s get to RFK Jr. here. I understand you wrote that book [Vaccines Did Not Cause Rachel’s Autism] … partially in response to him, and then he wanted to debate you on Joe Rogan’s podcast. Elon Musk, Steve Bannon and Roger Stone somehow got involved, and you’ve talked with Kennedy multiple times. What’s the full history between you and Kennedy?

A: In 2017, he had said that he was going to be appointed in a leadership role in vaccines with the Trump administration, and I got asked by the leadership of the National Institutes of Health to speak with Bobby, to explain to him why vaccines don’t cause autism based on the experiences of my daughter and my research. So it was a series of discussions … I’m concerned that in [the health and human services secretary] role, he will bring his antivaccine activism to Health and Human Services and promote a decline in vaccine infrastructure.

Q: What’s the role that he plays in the antivaccine movement?

A: Well, first of all, the antivaccine movement is not based on a few personalities. It’s wide-ranging. It’s a pretty vast ecosystem that includes American politics and political parties—it includes Fox News, it includes prominent podcasters—but he is one of the more outspoken and well-known antivaccine activists.

Q: “Whac-A-Mole” is a term that you used to describe having to respond to [vaccine opponents’] arguments. But can you sum up what Kennedy gets wrong about vaccines?

A: Well, he’s hard to pin down because one of the things I talked about today is the goalposts keep changing. He still talks about vaccines causing autism, which has been completely debunked. There’s not even a plausibility at this point. But he’s also made other statements about vaccines.

Q: What would Kennedy’s confirmation mean for the future, specifically, of the National Institutes of Health and the flow of federal research funding to U.S. colleges and universities and to certain research projects at those institutions, such as on vaccines?

A: It’s an important question, and the answer is we don’t know. We just don’t know how this is going to play out and how aggressive he will be from that context. My hope is that he doesn’t use his position to attack vaccines and to dismantle our very effective vaccine infrastructure, especially for pediatric immunizations and the elimination of childhood infections. But I don’t think we know.

Q: How do you think that the U.S. got to this point where someone like Kennedy is being nominated for this top role?

A: The antivaccine ecosystem … has evolved over time, starting in 1998 with false assertions around autism. I think the big game-changer is how the antivaccine movement got adopted by a major political party starting around the 2010s. I think that really amplified it, gave it funding, gave it political relevance. I think that’s a big piece to this. And the third piece is how it’s globalizing. [In his speech, Hotez noted that the antivaccine movement appears to have spread to Latin America and Africa.]

Q: Would Kennedy bring anything beneficial to the role of secretary?

A: I only have interacted with him on his positions on vaccines, which clearly show a lack of understanding of the science behind vaccines. How will he be in other sectors? I don’t know.

Q: Is there an effective approach, especially one that academics and universities could take, to lessen that skepticism of vaccines in the future?

A: It’s going to be hard. If this becomes the position of the federal government—to adopt antivaccine viewpoints—that’s very powerful. So academic institutions can do what they can. I think there’s a few things we need to do. We need to expand science communication opportunities for young faculty and postdoctoral fellows and graduate students. We have to train a new cadre of science communicators. I think that’s one. I think, second, we have to actually counter the disinformation when statements are made … So I think that’s a second component. So the first is enhancing communication, second is countering the disinformation. Third are protections for scientists, because it’s not only the science that’s under attack, but the scientists as well.

Q: When you’re talking about science communication, you’re talking about actually teaching scientists how to communicate as part of their training to become scientists?

A: That’s right. Most places don’t do that.

Q: Anything else you’d like to add?

A: I don’t know that it’ll stop at Kennedy. I’m worried that the first round of appointments suggests a very aggressive hostility towards science and scientists, and I’m worried.