You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

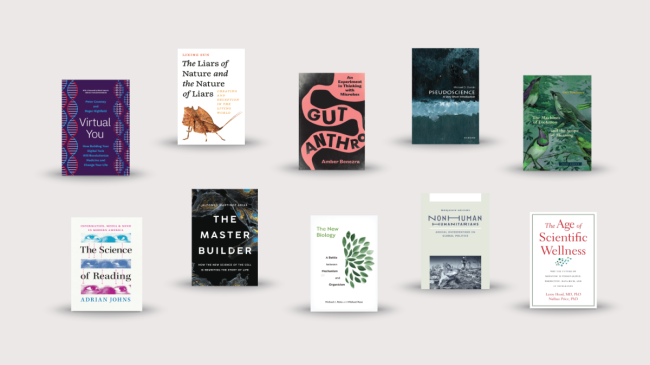

Jen Kim/Inside Higher Ed

The latest catalogs from scholarly presses are full of reminders—were any more needed—that a new presidential election cycle is grinding to a start, if indeed the last one ever really ended. I started to compile a list of electoral-adjacent books for this column, only to feel an urge to go outdoors and forget about what the next 20 months have in store. (At times there are definite therapeutic benefits to seeing squirrels.)

Returning to work, I started to assemble a different list. Several recent or forthcoming titles focus on the natural world, including the human organism and how it navigates its environments. Here follows a digest of some books that seemed particularly interesting. Quotations come from descriptions by the presses. All titles have been or will be published this year.

Three of the titles promise insights into developments in the life sciences. Alfonso Martinez Arias’s The Master Builder: How the New Science of the Cell Is Rewriting the Story of Life (Basic Books, August) “draw[s] on new research from his own lab and others” to challenge the genome-centric perspective of recent decades. It seems that “nothing in our DNA explains why the heart is on the left side of the body, how many fingers we have, or even how our cells manage to reproduce.” These and other important determinations are made through “a thrillingly intricate, constantly moving symphony of cells.”

That perspective is in general accord with Michael J. Reiss and Michael Ruse’s line of thought in The New Biology: A Battle Between Mechanism and Organicism (Harvard University Press, June). Acknowledging the explanatory value of treating biological processes as “a more complicated version of physics, one that can be reduced to the behavior of organic molecules,” they nonetheless emphasize the “need to view life from the perspective of whole organisms to make sense of biological complexity.” While their subtitle refers to a “battle” between mechanistic and organicist thinking, the authors themselves offer a pluralistic take: “Organicist and mechanistic approaches are not simply hypotheses to be confirmed or refuted, but rather operate as metaphors for describing a universe of sublime intricacy.”

At some point, that intricacy gives rise to organisms capable of emitting (and responding to) signs. Gary Tomlinson’s The Machines of Evolution and the Scope of Meaning (Zone Books, February) incorporates “emergent thinking about evolution, new research on animal behaviors, and theories of information and signs” in search of “the origin and place of meaning in the earthly biosphere.” Meaning making is not a human monopoly. Nor is it available to all creatures great and small. The author “discerns limits to its scope and identifies innumerable life forms, including many animals and all other organisms, that make no meanings at all.” But for the animals capable of generating and understanding signs, “they shape meaning-laden lifeways, offering possibilities for distinctive organism/niche interactions and sometimes leading to technology and culture.”

The semiotician Umberto Eco memorably defined the sign as anything that can be used to tell a lie. Humankind has no monopoly on that skill, either. Lixing Sun’s The Liars of Nature and the Nature of Liars: Cheating and Deception in the Living World (Princeton University Press, April) treats the natural order as swarming with prevaricators: “Possums play possum, feigning death to cheat predators. Crows cry wolf to scare off rivals. Amphibians and reptiles are inveterate impostors. Even genes and cells cheat.” Dishonesty is an evolutionarily beneficial policy, “giv[ing] rise to wondrous diversity.” The ability to “exploit honest messages in communication signals and use them to serve [an organism’s] own interests” or to “exploit the biases and loopholes in the sensory systems of other creatures” is “a potent catalyst in the evolutionary arms race between the cheating and the cheated.”

As a possible antidote to bio-cynicism, we have Benjamin Meiches’s Nonhuman Humanitarians: Animal Interventions in Global Politics (University of Minnesota Press, June). Taking up “the role of animals laboring alongside humans in humanitarian operations,” the author “examines how these animals not only improve specific practices of humanitarian aid but have started to transform the basic tenets of humanitarianism”—in particular its anthropocentrism. Through “integrating nonhuman animals into humanitarian practice, several humanitarian organizations have effectively demonstrated that care, compassion, and creativity are creaturely rather than human.”

The organisms Amber Benezra studies in Gut Anthro: An Experiment in Thinking With Microbes (University of Minnesota Press, May) are intimately involved with humanity, for good and for ill. Moving between a genome sciences lab in the United States and a field site in Bangladesh, the book interrogates how “the interrelationships between gut microbes and malnutrition in resource-poor countries” are handled across disciplines. The author considers “how microbes travel between human guts in the ‘field’ and in microbiome laboratories, influencing definitions of health and disease, and how the microbiome can change our views on evolution, agency, and life.”

Two co-authored books anticipate the shape of things to come for the human body itself—at least for humans with access to good health care.

Instead of “wait[ing] for clinical symptoms to appear before they act”—then dosing patients with medication and “invasive procedures from which they derive no benefit”—doctors will have access to the genomically informed treatments described by Dr. Leroy Hood and Nathan Price in The Age of Scientific Wellness: Why the Future of Medicine Is Personalized, Predictive, Data-Rich, and in Your Hands (Harvard University Press, April). Besides our genome maps, they will use data from blood tests “and hundreds of other inputs, all analyzed by artificial intelligence” to “detect the early onset of disease decades before symptoms arise, revolutionizing prevention.”

Peter Coveney and Roger Highfield’s Virtual You: How Building Your Digital Twin Will Revolutionize Medicine and Change Your Life (Princeton University Press, March) describes similar developments in terms of a cyber-doppelgänger that will be able to “help predict your risk of disease, participate in virtual drug trials, shed light on the diet and lifestyle changes that are best for you, and help identify therapies to enhance your well-being and extend your lifespan.”

Adrian Johns looks at an earlier moment of progress-mindedness in The Science of Reading: Information, Media, and Mind in Modern America (University of Chicago Press, April). In the early 20th century, researchers began “devis[ing] instruments and experiments to investigate what happened to people when they read” in order to study “how a good reader’s eyes moved across a page of printed characters, and they asked how their mind apprehended meanings as they did so.” What they learned then shaped classroom instruction, as well as public awareness of “drastic informational inequities, between North and South, city and country, and white and Black.”

For every stride forward, there seems to be a step or two backward of the sort anatomized by Michael D. Gordin in Pseudoscience: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, March). Unfortunately the term itself is emotionally charged and slippery of definition. And even if we agree that alchemy, astrology, “pyramid power” and T. D. Lysenko’s contributions to Soviet agricultural science all qualify, it is not clear that it’s possible to identify “a simple criterion that enables us to differentiate pseudoscience from genuine science.” The author examines particular cases of “doctrines that are often seen as antithetical to science,” past and present, arguing that, from them, “we can learn a great deal about how science operated in the past and does today.” No doubt it will be banned from some libraries.