You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

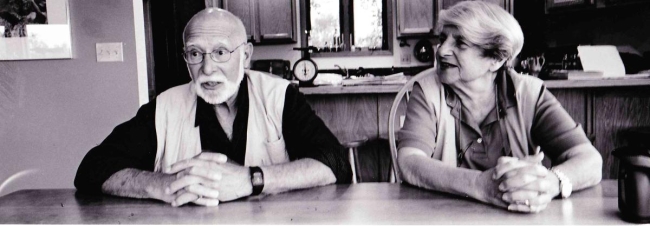

The author’s grandparents Ed Yellin and Jean Fagan Yellin. Ed Yellin’s conviction for contempt of Congress for refusing to answer questions from the House Un-American Activities Committee was reversed on a technicality by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Courtesy of Benjamin Mitchell-Yellin

These are scary times for teachers and academics, and the situation is only getting worse. The pace and scope of educational gag orders, laws regulating what can and cannot be taught about “divisive” topics, such as race in America, is increasing.

Texas, where I live and teach at a public university, saw the passage of new legislation last year regulating K-12 curricula around issues of race. This caught my eye, because it will affect what my children learn in school. But truth be told, the anti–critical race theory agenda driving this legislation has been on my radar for some time now, since it makes me worried for my academic career. I teach and publish on topics such as racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

At the moment, my state is not on the growing list of those with pending or enacted legislation targeting institutions of higher education. But it seems only a matter of time. Just this past week, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick announced his desire to see legislation dismantling tenure protections for Texas public university faculty who teach critical race theory. The optimistic take is that this is mere posturing for the coming election cycle. I’m not so sanguine.

Why am I so worried? Because of what the past and present portend.

Teachers all over the country are even more under the microscope than just a year ago. The Texas legislation includes provisions that effectively deputize parents to police those working hard, for little pay, to educate their children. Making matters worse, the language in these bills is often vague. With their livelihoods on the line, who could fault teachers for playing it safe and shying away from presenting students with unpopular truths?

And it’s not just those explicitly targeted by these bills who should be alarmed. Even though it doesn’t (yet) apply to higher education, the legislative attack on the free discussion of ideas here in Texas is already having a chilling effect on college campuses. A colleague recently wondered aloud how much longer she’d be able to teach Black history; in the next breath, she worried about the risks of doing so. I don’t blame her. Indeed, I share her concern.

It’s tempting to think this is just another outrage cycle that will soon pass and that, in the meantime, we can rely on the protections afforded us by institutional commitments to academic freedom and our individual right to free speech. But we should resist the temptation. When push comes to shove, there’s no guarantee our universities will have our backs. And even if these laws are found unconstitutional, which I hope they will be, it will come too late. To generate the kind of test case typically required for the courts to decide the issue, someone will need to be prosecuted for something. In the time it takes to get answers, harm will be done.

How do I know? Because of what my family endured more than a half century ago.

My grandfather Ed Yellin was summoned to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee in the winter of 1958. Citing the First Amendment, he refused to answer questions about his ties to the Communist Party. The saga dragged on for five years, until his conviction for contempt of Congress was reversed on a technicality by the U.S. Supreme Court in the summer of 1963.

Together with my grandmother Jean Fagan Yellin, he wrote a memoir about this ordeal. In Contempt: Defending Free Speech, Defeating HUAC (University of Michigan Press, 2022) contains some important lessons for those of us concerned with combating similar forces in the current moment.

As my grandparents put it, with a nod to Henry David Thoreau, “it isn’t much fun to be the friction that slows the machine.” It’s hard to know what effect their ordeal had on their careers. At one point, my grandfather’s National Science Foundation fellowship was revoked, and his plans to pursue his doctoral research as a “special student” at Johns Hopkins University were scuttled. They had to move their young family across the country, from Baltimore to Urbana, Ill., on short notice and a shoestring budget.

Despite all this, they were both able to complete their degrees at the University of Illinois and had very successful academic careers. Ed retired as professor emeritus in the Department of Physiology and Biophysics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and Jean retired as Distinguished Professor Emerita of English at Pace University, both in New York. But the toll on their young children was clear. They endured social ostracization when neighbors got word of their father’s conviction. Too young to understand he was only leaving for a Supreme Court hearing in D.C., they worried this was the last time they’d kiss their father goodbye. The whole family lived for some time haunted by the specter of his yearlong jail sentence. These heartbreaking details show the collateral damage wrought by government persecution for ideas, even when the one being persecuted doesn’t serve time and is eventually acquitted.

Their story also illustrates the important truth that systemic injustice can outlast those who set it in motion. My grandfather appeared before HUAC years after Senator Joseph McCarthy was censured, and even after his death. Cries of a new McCarthyism are useful to contextualize what’s going on, but it’s important not to fetishize particular figures. Fixing the current problem isn’t simply a matter of ensuring the Dan Patricks and Donald Trumps of the world don’t occupy positions of power.

At the same time, the solution isn’t just about replacing bad laws with good ones. True, these are mechanisms by which injustice gets institutionalized, but attending to them alone can serve as an evasive maneuver.

The U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari because my grandfather’s “case presented constitutional questions of continuing importance.” And yet they did not take up the constitutional questions, instead reversing his conviction for refusing to testify on the grounds that HUAC violated one of its own rules. Disappointingly, there was no discussion of the First Amendment issues. Focusing just on rules and policies is one way the ideology underlying the system escapes scrutiny. And it’s the ideology that really powers the machine.

Surely, political participation is key to resisting current efforts to prohibit the discussion of “controversial” ideas. Knocking on doors and getting out the vote are key, but they aren’t enough on their own. This is a struggle over who gets to shape the collective memory. How things turn out will depend, in crucial part, on shaping the hearts and minds of our fellow citizens of all ages. Those flexing their political muscle to regulate what gets taught in classrooms across the country understand this. Those of us doing the teaching need to as well.