You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

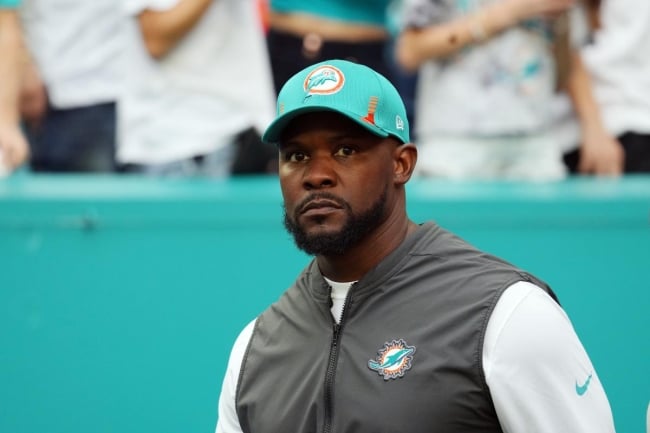

Former Miami Dolphins head coach Brian Flores

Mark Brown/Getty Images Sport/Getty Images

National Football League commissioner Roger Goodell sent a memo to all 32 professional teams earlier this month in which he deemed the lack of diversity among the league’s head coaches “unacceptable.” His memo was in response to a racial discrimination lawsuit that former Miami Dolphins head coach Brian Flores recently filed against the NFL and its teams. As I read the lawsuit, parallels between this situation and what happens to Black men in head coaching roles at colleges and universities in the United States—especially those with powerhouse revenue-generating football and men’s basketball teams—became apparent.

Flores was fired last month after a three-year tenure, despite leading the Dolphins to its first pair of consecutive winning seasons in nearly two decades. Also last month, the Houston Texans fired David Culley, another Black head coach, after just one season.

In his lawsuit, Flores argues not only that Black coaches are far less likely to get hired, but that those who are hired are given fewer opportunities to succeed and afforded less time to establish themselves. The suit alleges that since 2012, Black coaches have been fired on average after 2.5 years, while white coaches have averaged nearly 3.5 years on the job.

This phenomenon can be seen in intercollegiate athletics, too. One example is Florida State University’s abrupt firing of head football coach Willie Taggart, a Black man, after just 21 games—not even two full seasons. His record was 9 and 12. We have seen worse. Most white coaches almost always enjoy a far longer transition period to build their staffs and to recruit players whom they believe will best position the team for future success. There is typically some recognition that they are playing with student athletes whom their predecessors recruited.

Flores alleges in his lawsuit that Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross attempted to bribe him to behave unethically. Although I can think of no recent examples of this occurring between Black college coaches and athletics directors, it does point to a broader phenomenon that occurs at predominantly white postsecondary institutions: racialized power asymmetries. According to the NCAA Demographics Database, 88 percent of athletics directors at member institutions (excluding historically Black colleges and universities) in 2021 were white. Only 7 percent of head men’s football coaches, 14 percent of head men’s basketball coaches and 15 percent of head women’s basketball coaches across all divisions (excluding HBCUs) are Black.

Like in the NFL, the overwhelming majority of executives to whom Black head coaches ultimately report in intercollegiate sports are white. Hence, they are left to navigate the same expectations and pressures as white head coaches, plus the racial politics that sometimes complicate cross-racial workplace interactions between Black professionals and powerful white leaders to whom we report.

Just as about seven out of 10 NFL players are Black, the majority of football and men’s basketball players at big-time college programs are Black. In a 2018 USC Race and Equity Center report, “Black Male Student-Athletes and Racial Inequities in NCAA Division I College Sports,” I noted that Black men made up 2.4 percent of undergraduate students enrolled at the 65 universities in the Power Five sports conferences—the Atlantic Coast Conference, Big Ten Conference, Big 12 Conference, Pac 12 Conference and Southeastern Conference—but comprised 55 percent of football teams and 56 percent of men’s basketball teams on those campuses. In the NFL and in college, it is mostly white male coaches, conference commissioners and NCAA executives who profit from the labor of Black athletes. The Flores lawsuit creates an important window of opportunity for higher education institutions in the Power Five and across all NCAA divisions to first acknowledge and then aim to strategically address the demographic mismatch between players and their coaches on revenue-generating sports teams (and in women’s basketball, too, where 41 percent of Division I student athletes, excluding those enrolled at HBCUs, are Black).

After the firings of Flores and Culley, the NFL was initially left with one Black head coach, Pittsburgh Steelers coach Mike Tomlin. (The Dolphins have since hired Mike McDaniel, who is biracial, while the Texans hired Lovie Smith, who is Black.)

The paucity of Black coaches in the NFL speaks to a colossal policy failure. The Rooney rule, a policy the NFL introduced in 2003, requires teams to interview at least one person of color for head coaching and general managing and equivalent front office leadership jobs. While the NCAA and athletics conferences in higher education have not adopted the Rooney rule in policy, many institutions engage in an often-unspoken version of it in practice. That is, they interview one or a few obligatory Black candidates for head coaching positions, knowing full well they have no serious intent to hire them. White decision makers in professional sports, as well as those at higher education institutions, must stop wasting Black coaches’ time.