You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

It is 2018 and we still have a crisis with the faculty. For 30 years critics have proclaimed the tenure-track and adjunct models of faculty broken.

Tenure-track models overemphasize a very narrow definition of research and do not encourage or provide accountability for quality teaching or improvement of teaching. For example, studies demonstrate that only 25 percent of faculty are excellent at both research and teaching. Furthermore, the tenure track can commit institutions to wages beyond retirement and to fields of study where enrollments may no longer exist.

Adjunct lines provide no institutional stability for the teaching force and bring in droves of fluctuating staff with limited or no experience teaching for a particular institution. Many adjuncts are not granted office space and have little support in acclimating to a particular campus, which leaves students without instructors available for office hours and unprepared for mentoring.

In addition, adjuncts are left out of institutional discussions about learning goals, course assignments and textbook selection, and they are excluded from professional development, evaluation and feedback. Lastly, the adjunct model has serious human and moral costs: faculty members often live on poverty wages with no benefits, job security or career trajectory. These adjunct faculty have received Ph.D.s from universities without having been informed of the often poor job prospects in their fields. Institutions continue enlarging their doctoral enrollments amid a significant decline in reasonable jobs.

As part of the Delphi Project on the Changing Faculty and Student Success, we have long described the need to better support faculty off the tenure track as a short-term solution to the larger faculty crisis. But that is only a short-term solution -- one with increasing popularity but very limited long-term utility.

While we can eradicate some of the most egregious aspects of the growing adjunct and contingent roles with better support, we also have to rethink faculty roles more comprehensively for the future. With the growing visibility of struggling adjunct faculty and the clear links between their struggle and the very structure of their roles, the academy can no longer ignore this essential work.

What should the faculty look like in the future to overcome this crisis once and for all? We recently developed a survey of key stakeholders across higher education including boards, policy makers, administrators at all levels, faculty members of all types, disciplinary societies and unions to examine their views about the future of the faculty.

One of the myths that circulates in academe is that faculty and administrative views of the faculty are so diametrically opposed that discussions of future faculty roles are not possible. The myth foregrounds two stereotypes: professors (and their unions) who cling to luxurious tenure-track roles, and administrators driven by neoliberalism and the desire to deprofessionalize all faculty members. The survey findings challenge these views and find many points of consensus that can lead to a vision of the faculty for the future.

Although professors and administrators/policy makers share many common perspectives, unions and unionized faculty showed no lesser willingness to consider these features. Some key points of agreement are:

- We need to hire more full-time faculty (though not necessarily on the tenure track) and cease our overreliance on part-time faculty.

- We need to professionalize all faculty through ensuring academic freedom (potentially outside tenure systems), inclusion in shared governance, professional development, a system of promotion and decision-making related to curriculum and students. This point was seen as critical to any faculty role or contract type.

- Nontenured faculty need longer contracts: semester to semester and year to year are just too short. Three- to seven-year contracts, with increased durations over time, are seen as more reasonable.

- We need more emphasis on teaching, whether through tenuring faculty for teaching or hiring full-time faculty members into teaching roles on long-term contracts.

- All faculty should have a scholarly role -- not necessarily conducting original research, but attending conferences and keeping up with developments in one’s field and conceptualizing scholarship more broadly to include research on teaching.

- Faculty need differentiation and customization of role, and this should be desirable. Not all faculty members need to focus solely on teaching and research, and faculty should not focus on the same role their whole careers. For example, they may focus on teaching for a while, then shift to service or administrative roles, then research.

- Faculty members need flexible work policies and contract options. For example, flexibility around stop-the-clock policies, part-time tenure-track routes and consortial job sharing of part-time positions create variability for full-time positions to accommodate family or create better working conditions.

- Faculty roles should emphasize collaboration and working across departments, within units and with outside groups to foster student success and cross-disciplinary research and service.

- Faculty members should focus on student success and learning as the most central activity; particularly important is support for students of color and first-generation and low-income students.

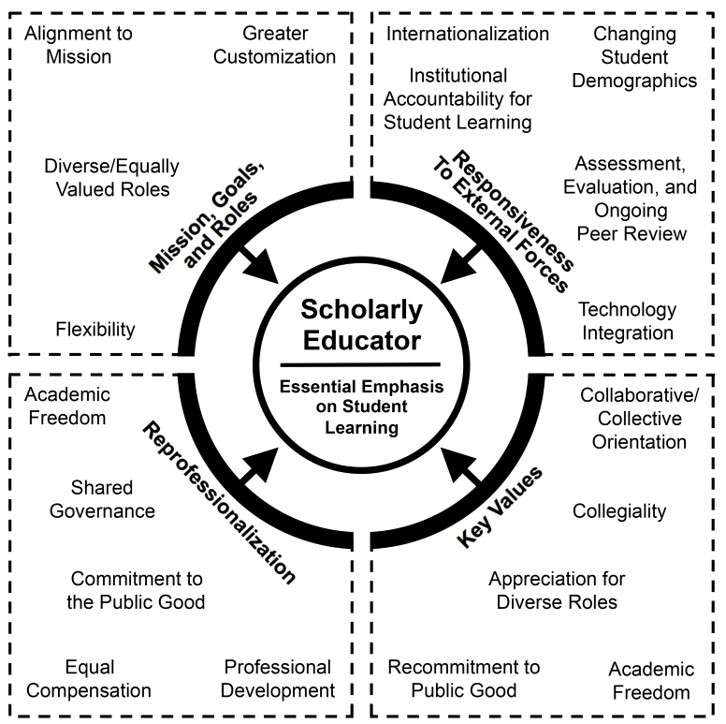

There are several other points of agreement, which indicate some clear ways forward for academe. We recently came out with a book that highlights a model in keeping with this shared vision: Envisioning the Faculty for the 21st Century (Rutgers University Press). This diagram captures the key features.

Our survey asked not only about future faculty models or roles but also the feasibility of these features becoming part of the enterprise. There was pessimism about the funding to support this vision for the faculty and about bureaucratic complexities in implementing these approaches.

We can engineer our way to the moon, we can map the human genome, we can cure polio, but we cannot realign our budgets to support the faculty we all believe in?

We can develop complex shared-services partnerships and systems with education companies, nonprofit organizations and governments, yet we cannot work out the contracts, policies and procedures to implement the vision for a future faculty? This seems an easy hurdle.

Ironically, those who do implement new models have found it fairly easy. I have spoken to people at dozens of campuses and departments that are quietly revising their faculty to look much more like the vision noted above in the emerging consensus. But these same leaders voice a fear about being too far out from what other campuses are doing.

Campuses do not embrace this work with a sense of pride as leaders. I think the time has come for institutions to stop being quiet and start seeing this work as essential to satisfying the broad mission of student and institutional success. Ample evidence shows that the future faculty model outlined above would much better support students. Nationally, leaders have been called upon to make student success a primary focus (see Aspen Institute Initiative), and championing these new faculty models would be clearly aligned with these efforts.

My challenge to the academy is this:

Proudly promote your innovative work to implement new faculty models that support student learning and success. Take ownership of your role at the forefront of the evolution of the higher education enterprise.

It is time that foundations and policy groups find ways to support this work, bringing it out of the shadows and demonstrating the simple yet elusive fact that it can be done, and that reconceiving sustainable faculty roles represents a high priority for the future of academe.