You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Last week, the Department of Education walked back from its plans to develop a comprehensive college ratings system. In its place, the department plans to release “easy-to-use tools that will provide students with more data than ever before to compare college costs and outcomes.”

There are already plenty of resources and tools to help students and families research these questions, provided by government (College Navigator), nonprofit organizations (College Results Online), and media outlets (U.S. News & World Report College Rankings), and lawmakers continue to call for more consumer information about college outcomes.

But is anyone actually using these tools, and are the interfaces, graphics and user experiences designed to actually help students? And how “easy to use” will these new tools be?

To better understand what works and what doesn’t, I recently co-wrote a report with Healey Whitsett, now of the Pew Charitable Trust, that provides best practices on how to design and deliver information to help prospective college students navigate the best programs available for them. The department should turn to these principles as it develops its new tools to maximize their effectiveness.

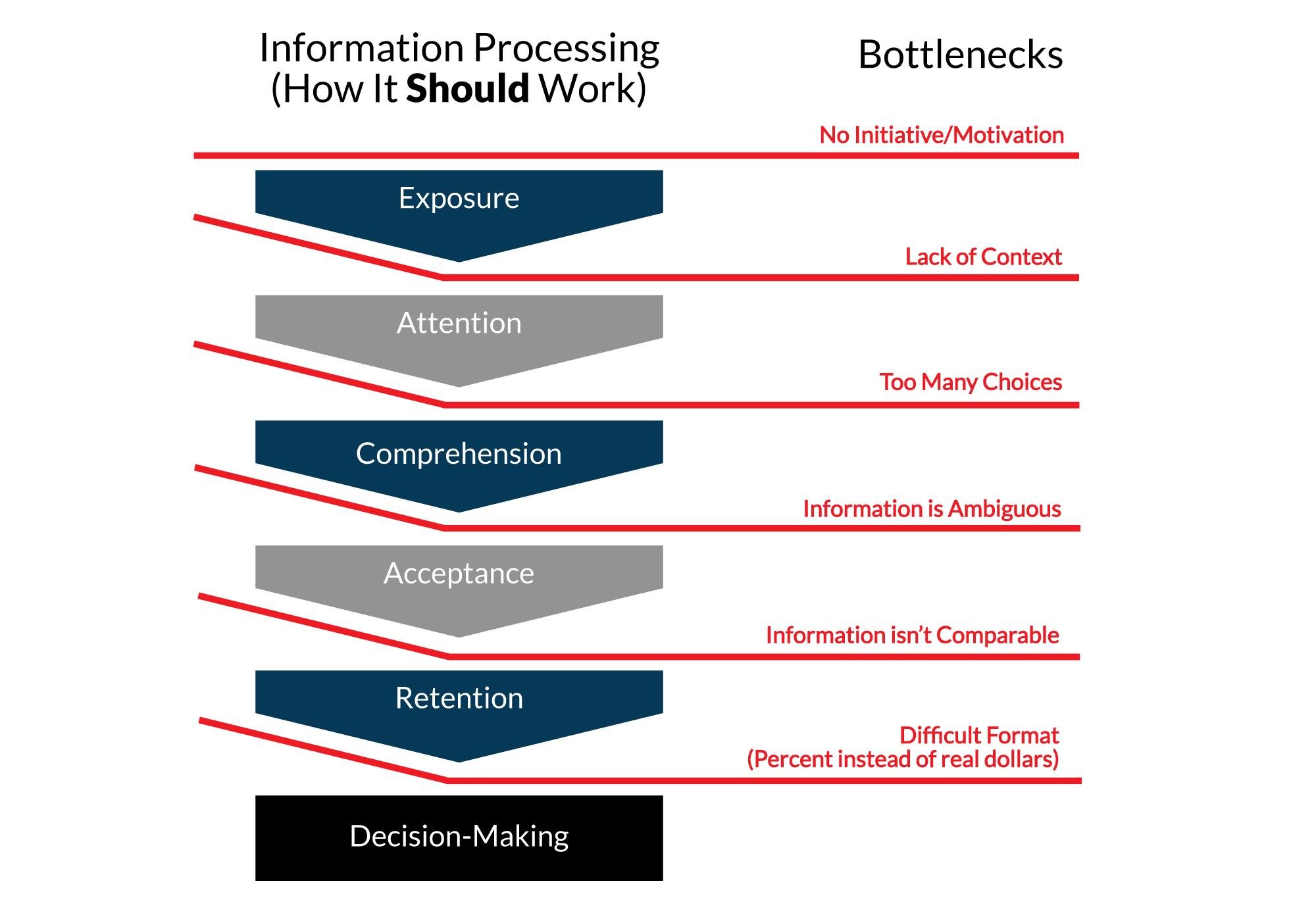

We synthesized scores of studies on behavioral economics, information search, retention, and bottlenecks that get in the way and break down the proper processing of information – and recommended ways to design tools so students get the information they need to make more informed decisions about where to go to school, what to study, and how to pay for it. We also recommend that designers target their efforts at students from low-income families, as unfortunately, they’re the least likely spend a lot of time searching for information.

For example, designers shouldn’t try and cram too much information in one place. Cognitive research tells us this overwhelms the reader and makes it difficult to comprehend and retain the information.

In one study, researchers compared individuals' interactions with the standard mortgage disclosure form, against a redesigned, better organized prototype: borrowers using the redesigned form were 38 percentage points more likely to correctly identify the amount of the loan, and 11 percentage points more likely to correctly identify their monthly payment amount. Since students are unable to identify how much money they took out in student loans, redesigning these forms makes a lot of sense.

The literature also demonstrates the importance of personally tailored information: Consumers are much more likely to identify, remember, and use information if it is personally relevant to them. That’s why broad national rankings are probably only so useful to students and families. In this regard, the Department seems to be on the right track by making the tools “customizable” to the user.

Our research also finds that higher education stakeholders shouldn’t present students with too many options of comparison. With 7,000 colleges and universities to choose from, it’s critical that we figure out manageable ways for students to compare a limited set of schools that tailor to their interests, or they risk facing what we call the “tyranny of choice.”

A study by Judith Scott-Clayton at the Community College Resource Center at Columbia University's Teachers College showed that too many choices in community college majors or programs may overwhelm and discourage students from persisting in and succeeding at earning a credential.

Furthermore, information should be as personally tailored as possible, as individually contextualized information is much more likely to be recalled and used in decision making.

Aspiring students must also be able to compare and contrast their school and loan choices. It would be very difficult to choose which school to attend if you knew the graduation rate of one and the list of majors of the other. They must be able to compare the same variables side by side.

Fortunately, it looks like Congressional leaders are interested in arming students with more information as well. In its white paper on proposals for reauthorizing the Higher Education Act, the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee called for “extensive consumer testing on what information is needed and how it should be presented” and to “[a]pply this research to any federally produced consumer tools and make the research available publicly to voluntarily inform the market.”

The House Education and Workforce Committee recently said, “Access to better information will empower students with the knowledge they need to make smart decisions in the college marketplace.”

We hope that the department will take note of this research as it designs this new tool and we also applaud department officials for committing to work with outside parties to design their own mobile apps and interfaces optimized for usability. After all, aspiring students can have all the data and information in the world, but if it’s not packaged and delivered in a way that’s useful to them, then we’re wasting our time.