You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

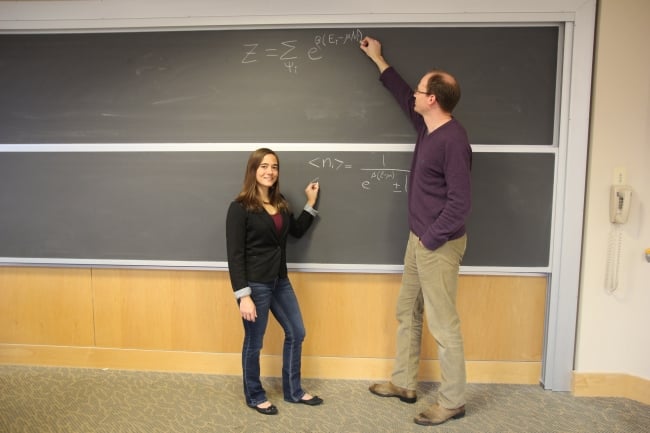

Katherine Aidala of Mount Holyoke (left), with a taller colleague, Spencer Smith

Photo by Grace Fitzpatrick, Mount Holyoke College

I am a five-foot-tall female physicist. You hear a lot about the challenges facing women in physics. These are real, and the percentage of physics bachelor’s degrees earned by women has stagnated at just over 20 percent for more than a decade. Being a woman in physics can be hard, but being a short physicist seems even harder to me. Why don’t we ever talk about the challenges of being short?

Gender is the most prominent feature that we use to categorize ourselves, beginning from the first question asked after we are born: Is it a boy or a girl? The hypothesis that women are less intelligent or less cognitively capable of certain tasks has been around for a long time. For a while it was attributed to brain size, then the Y chromosome, then hormones circulating in the body, and now prenatal hormone exposure.

For some reason, our society wants to believe that women aren’t as smart as men. When a woman feels out of place in a male-dominated environment, she is understandably tempted to attribute it to her gender -- and she may be right.

But when I find myself feeling out of place and not quite knowing why, I tend to blame it on my height. Whether on the athletic field, in an elevator, or in the lab, I am generally the shortest person present. At my height, 19 out of every 20 women I meet are taller than I am. The average man soars 10 inches above me. High heels cannot make up 10 inches.

As kids, we all wait to grow into the world around us, and the average 12-year-old is close to my height. It wasn’t until I was an undergraduate at Yale University that I had to admit the world would never be designed for me. I was somehow happily oblivious in college to the challenges faced by women, but the challenges faced by short people were obvious to me, every day. I could not reach things on high shelves in the labs and libraries. I could not sit with my feet flat on the floor with my back supported in many classroom chairs.

The challenges continued in my graduate research lab at Harvard University. I wasn’t large enough to flip the dewar that held our cryogenic microscope. I wasn’t strong enough to loosen a bolt. When I couldn’t find where my peers had put something, I learned to get on the step stool and look at their eye level.

I looked ridiculous using all my body weight at an awkward angle to pull a liquid helium tank down the hall. The cleanroom ran out of the small sizes of “bunny suits” that are required to enter the cleanroom fabrication facilities. Small people were expected to wear larger ones, since big people cannot physically fit into smaller ones.

The biggest safety hazard was the location of a hot plate in a fume hood. The point of a fume hood, a structure that allows you to put your hands into a space that has its own ventilation, is to keep toxic fumes on the inside, away from the air you breathe. Short people simply took a deep breath before sticking their heads into the fume hood.

My six-foot-tall female labmate didn’t have these problems.

I now work at a women’s college. The environment is eye-opening.

The brightest student in the class is a woman. The most studious student is a woman. The struggling student is a woman. The slacker is a woman. The geek is a woman. The most aggressive and most outgoing students are women. Even the student who talks the most in class is a woman.

When I need help reaching the screen at the front of the room to pull it down, it’s a 5’6’’ woman who comes to my rescue. Prizewinners are always women, and leadership positions always go to women. We may still categorize the people we meet, but it’s no longer based on gender.

I received the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers in 2010, considered one of the most prestigious awards bestowed upon young scientists. There were two things that statistically increased the chances of receiving the PECASE that year through the National Science Foundation: being a woman; and being named Ben. You are unlikely to hear the accusation that you won “just because your name is Ben,” yet women are told that they receive awards because of their gender, not their qualifications.

A women’s college naturally provides many female role models, but predicting effective role models is not straightforward. For some, identifying with a role model is critical to pursuing an unusual path, but a good match is not as straightforward as being the same gender, race, or sexuality.

I never needed or wanted female role models in physics. But I do need short role models in sports. Watching someone much larger than you excel on the field is not helpful. Seeing someone your size outcompete a larger person is motivating, and educational. One striking part of my interview at Mount Holyoke was how short the (male) dean of faculty was. I more recently met the (short, female) director of the American Association of Physics Teachers. I didn’t think I was looking for five-foot-tall role models in leadership, but maybe that’s because I hadn’t met any.

While I intellectually recognize that being a woman in physics has presented challenges, I viscerally know that being short is difficult. That I haven’t volunteered my race or sexuality suggests I’m white (which is true) and heterosexual (also true).

When someone speaks over me in a meeting or repeats my idea more loudly as their own, I assume it’s due to my physical stature, not because I’m a woman. And for all of you who are ever in a meeting and notice this happening, it’s your cue to say, “Thank you for reinforcing the point made by... .” That’s all it takes to change a frustrating environment into an affirming one, in a noncontroversial way.

If we all make an effort to do small things like that more often — to recognize that the categories by which we sort people are limited, and that talent comes in all shapes and colors and follows many different trajectories through life — then perhaps an essay like this will someday simply start with the statement: “I am a physicist.”