You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

I always thought it was strange to walk into drugstores and see cigarette cartons piled high as mountains behind the cashier. After all, I come from Ontario, Canada, where you can’t buy alcohol outside of special Liquor Control Board of Ontario stores. (Beer, it should be noted, is also available throughout the province at “The Beer Store” -- a name that’s even clear enough for beer-addled Canadians like Bob and Doug MacKenzie.)

So when I heard that CVS, the large drugstore chain, had decided to stop selling cigarettes, it was as obvious to me as the eventuality that the successful ALS “Ice Bucket Challenge” campaign will one day be co-opted by our new enemy in the Middle East (the “ISIS Bucket Challenge”).

Drugstores and pharmacies are supposed to further health. Promoting smoking does not. One health care industry professional quoted in The New York Times said: “Think of it this way: Would you find cigarette machines or retail stores in the gift shops in a hospital selling cigarettes? Of course not. I think it does give them a leg up.”

CVS announced the move along with a new name: CVS Health. CVS has moved from selling health care products to delivering health care services. It currently operates 900 “minute clinics,” where health care professionals deliver simple services like administering flu shots and prescribing antibiotics for garden-variety ailments.

It’s nice when organizations decide what they want to be when they grow up and then execute that vision. Too many institutions try to be all things to all people. Like colleges and universities.

***

Colleges and universities license their brands for many products that don’t have much to do with higher education.

There’s the BC hockey table (Go Eagles!):

The Emory rug (Go Eagles, again!):

UT duct tape (if you can’t hook ‘em, tape ‘em):

And UNC fragrances (smell like tar, or like a heel):

The news last week was that universities are licensing their brands to Kraft for Jell-O molds. While Kraft launched the university Jell-O product last year (to massive demand, apparently), 16 more institutions have been added, including these:

It’s clear to me exactly how this happened. All universities have trademark licensing offices. Many of these schools already license their brands for shot glasses. It’s a small step from shot glasses to Jell-O shot molds. Of course, this isn’t what the universities are saying. A spokesperson for University of Georgia said the molds are not specifically marketed for alcoholic shots: “Our look at it was plain and simple. Jell-O is a reputable product that has been on retail shelves for years. What we don’t control is the individual end user and what they use the product for. What the product was designed for is gelatin.” Or this from UNC: “The conclusion was that the Jell-O mold was a family- and fan-friendly product that shows school pride. It was consistent with other recently approved products, including a school-branded line of Pop Tarts.”

***

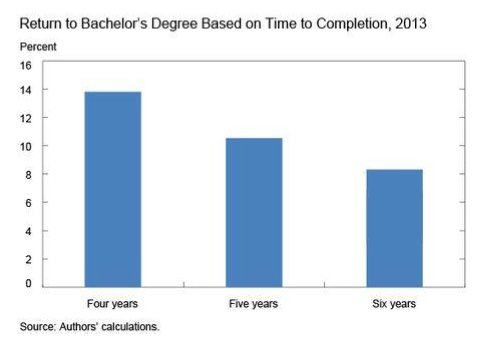

News coverage to date has focused on the mixed message the product sends to students who are subject to university policies and educational programs for alcohol and binge drinking. But how about the link between the Jell-O shot economy and the phenomenon of the six-year degree that is already too prevalent at the aforementioned institutions? A new study from the New York Federal Reserve shows that the return on investment from a 6-year degree is 40 percent less than that on a 4-year degree.

Then there’s the question of the purpose of trademark licensing. While universities undoubtedly have valuable brands, their mission isn’t to maximize revenue across multiple product lines. What is their mission? Based on a scan of Jell-O-brand universities, 60 percent fail to mention students AND learning in their mission statements (and forget about outcomes, tuition or return on investment, which are nowhere to be found).

Higher education mission statements tend to be multifaceted, complex and vague. Most include knowledge dissemination and research. Many include statements about furthering the public good. Often, there are so many bottom lines there’s effectively no bottom line at all. This makes it difficult for trustees to ascertain whether officers (or trademark licensing offices) are doing a good job and to exercise appropriate governance.

Like CVS, universities need to stop trying to be all things to all people. If their mission involves students AND learning, they should look at their current over-broad roster of activities and begin to cull those that are unrelated. They should also consider eliminating those that may be related, but where they do a poor job. See last week’s New York Times feature on how specialized institutions like the Fashion Institute of Technology or Harvey Mudd College punch well above their weight (in terms of rankings) when admitted students choose between a specialist and a generalist.

Institutions counting on licensing revenue from Jell-O shots and other products may find it difficult to focus solely on student learning. And nearly all institutions find it difficult to specialize.

CVS faced the same decision set. Cigarettes represented $2 billion in annual sales. It was hard to walk away from that.

But CVS made the strategic decision that they were in the business of health, a decision that ought to have a financial payoff down the line, according to an industry expert quoted in the Times: “When you stop selling cigarettes as a retailer, it sends a very big signal to the rest of the health care community that you are in the health care business. I do think that it’s going to open up many possibilities in all of the partnerships that they’re trying to create across the country.”