You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

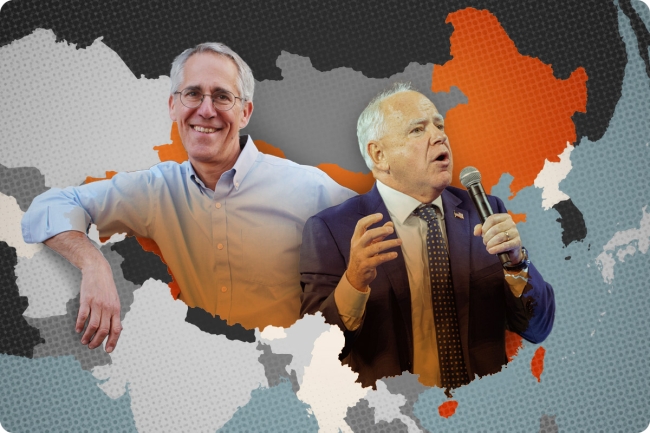

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Courtesy of Jeffrey Wasserstrom | Mahka Eslami/Middle East Images/AFP/Getty Images

A lot of scholars I know are historians based in the United States who work on cities that were either parts of the People’s Republic of China from the time it was founded in 1949 or became part of that country later, as Lhasa did in 1951 and Hong Kong did in 1997. Many of them spent a lot of time before 2020 visiting the urban centers they were working on. I did, too. This was only natural. We wanted to use local archives and simply walk the streets of the places where historical events that interested us occurred.

Not surprisingly, when COVID-related travel restrictions began to loosen, many of these historians immediately set out trying to figure out how to get back to the places in the PRC that meant the most to them. One set, though, did not: specialists in Tibetan and Xinjiang studies. One way to sum this up is that my circle of friends includes a lot of Couldn’t Wait to Returners and some Couldn’t Returners.

But I don’t fit into either camp. Shanghai and Hong Kong are the cities I’ve worked on the most. I first went to each in the mid-1980s, but I have not been to Shanghai since 2018 or Hong Kong since 2019. I have no plans to go to either.

Hearing this, some colleagues ask me if I have been banned due to the work I have done on human rights and protests. I have not been.

I took a break from going to the PRC once before. That hiatus, which lasted from the late 1980s until the mid-1990s, was due in part to how I felt about a brutal crackdown and a sense that the Chinese Communist Party was taking the country in the wrong direction. The same thing can be said about my not going now.

Some people reading this far might imagine that I am disappointed when friends itching to get back to the PRC tell me they have been back or are planning to go back. Not so. Some readers might also imagine that I discourage my students from going. That is also not true.

We live in an era of binary thinking and all-or-nothing stances, so I have been finding it hard to convey the nuanced thinking behind my position on the to-go-or-not-to-go question. Curiously, though, something recently happened in a realm unrelated to academia that provides a useful way to articulate my position: Vice President Kamala Harris chose Governor Tim Walz to be her running mate.

This is relevant here because, much to my surprise, I find myself in the position, for the first time in my life, of having some things in common with a candidate for vice president. I have even discovered that I once had an interaction with him.

I’ll begin with the things that Walz and I have in common.

Like Walz, I first went to the PRC at the age of 25 in a year associated with student protests. He went in 1989. I went in 1986, a year when small demonstrations took place that helped set the stage for the much bigger Tiananmen ones to come. The young people he met during his first trip to the PRC—part of a generation of young people who dreamed of living in a freer country and who were willing to take risks to try to push the CCP to do better—made a deep and lasting impression on him. The same is true for me.

A key difference between our first trips was that only he faced a to-go-or-not-to-go dilemma. In the spring of 1989, he stopped in Hong Kong, then still a British colony, on his way to taking up a position teaching on the mainland. He had to decide whether to scuttle his plans when news reached Hong Kong that soldiers had fired on unarmed civilians on Beijing boulevards.

Some people urged Walz to head back to the U.S. after the killings, which in Chinese are referred to as the June 4 Massacre. Many at the time felt it was unsafe, unconscionable or both to travel to the PRC as if things were normal. But he stuck with his original plan. People-to-people ties would be important in U.S.-China relations going forward, he felt, and fostering cross-cultural understanding through classroom engagement remained a worthy goal.

In 1989, at the age of 28, I might have joined the chorus of those urging Walz to head home. But three and a half decades later, I’m glad that he went to the PRC.

If he hadn’t gone, he might not have developed his enduring concern about CCP human rights abuses. He might not have met with the Dalai Lama and the now imprisoned Joshua Wong. He might not have spoken out about repression in Tibet and Hong Kong.

He also might not have served on the Congressional-Executive Commission on China and taken the lead in its 2014 hearing marking the 25th anniversary of Tiananmen. Being involved in that event gave him the chance to make compelling opening remarks, which looked back to his decision in 1989, and ask thoughtful questions of the experts the CEEC invited to testify.

This brings me to the exchange we had. I was one of the experts who spoke about the protests and repression of 1989 at the hearing and then fielded questions from Walz. They were astute ones about issues of history and memory, and ones to which he genuinely seemed interested in hearing our responses.

Why, if we had met a quarter-century earlier, might the 28-year-old me have urged Walz not to go to the mainland? To answer this, I need to go into details about my first PRC trip. It began in August 1986, when I set off from Berkeley to spend an academic year doing doctoral research in Shanghai on the city’s pre-1949 student movements.

A few months after I arrived, my historical interests and contemporary events collided. The city witnessed its first student-led protests in decades that were not, as the Red Guards’ actions of the 1960s were, fueled by fervent devotion to a charismatic leader.

The protest surge I witnessed, which began in Shanghai and other cities south of the capital in December and ended with a New Year’s Day 1987 march in Beijing, felt oddly familiar. Spending time on streets watching marches and on campuses reading posters, I kept being reminded of photographs and texts I had been encountering in the archives. The strongest parallels were to the mid- to late-1940s protests that challenged Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government. Then, too, students living in an autocratic setting clamored for change, calling for more of a say in politics and for officials to be more responsive to the populace.

The 1986–87 demonstrations are now largely forgotten, but they were important. They helped set the stage for the epochal struggle that came two years later and involved similar grievances, such as anger at corruption and frustration at the way the CCP limited freedom of expression and micromanaged people’s private lives.

I left the PRC in the middle of 1987, returned to Shanghai briefly for a conference in 1988, but was in California throughout 1989. It was through published reports and television coverage that I followed the news of that year’s inspiring April student rallies at Tiananmen Square and massive May demonstrations in which workers and members of other social groups joined youths on urban streets and plazas across the PRC. That was also how I followed news of that June’s crackdown, which included, along with the killings in the capital, a smaller massacre in Chengdu and waves of arrests across the country.

I was shattered by the news that June. No one I knew was killed or arrested, but I felt a direct connection to the horrors, since the victims were just like the people I had gotten to know and care about while in the PRC.

I did not make a conscious decision to stay out of the country, but I did not return to it until 1996. It did not feel right to go to there, especially as a general tightening of controls was taking place and the official media was either grotesquely distorting the story of Tiananmen or pretending that nothing had happened in 1989.

I started going again after there were several years of heartening signs of a shift back toward liberalization. Political reform was off the table, but the CCP leaders had decided that, to avoid losing power the way their Soviet bloc counterparts had, they needed to allow people some of the personal choices the Tiananmen generation had demanded.

My 1996 return trip was followed by another in 1999. Then I started going more regularly, every year or two, and sometimes two or three times in a single year, often to Shanghai and sometimes to other places instead or as well, most often Beijing or Hong Kong.

Beginning in 2014, I started going most often not to Shanghai but to Hong Kong, which the 1997 handover had transformed into a part of the PRC that was supposed to enjoy a high degree of autonomy. I became intensely interested in protests there aimed at defending that special status in which students of Joshua Wong and Agnes Chow’s millennial generation and then later Gen Z activists played central roles.

Those Hong Kong protests were unique, but they reminded me of past ones that had transfixed me. They had things in common with the pre-1949 protests covered in my dissertation, the 1986 ones I watched unfold in Shanghai and the 1989 ones in Beijing I followed from a distance.

My two last trips to the PRC were to Hong Kong in June and December of 2019. During the first, I took part in what turned out to be the city’s last big legal vigil to commemorate the victims of 1989. During the second, I watched the giant Dec. 8 march that turned out to be the second-to-last protest involving more than 100,000 people ever held in Hong Kong.

My short Columbia Global Reports book Vigil: Hong Kong on the Brink, which was finished before my last visit to the city and is largely about the protest surge that was still underway when I made that trip, was published in February 2020. I planned to return to the city to do public launch events for the book. There has been no way for such events to take place, due initially to COVID restrictions and then, after Beijing imposed a harsh National Security Law on the city in June 2020, due to the political environment.

In the wake of many months of disheartening news coming out of Hong Kong of arrests and political trials and the battering of the press and civil society, I not only abandoned hope of being able to give public talks about my work in the city but started wondering if I would ever go there again. This was also linked to a general sense of dismay at the direction the PRC had been heading for quite some time. The grotesque, long-standing abuses of human rights in Xinjiang and Tibet and a general sense that many people across the PRC are finding less room to maneuver in the Xi Jinping era contributed to this pessimistic feeling.

In some ways, my current break from going to the PRC feels like the 1988-to-1996 one, but due to Hong Kong’s situation there is also an added element now: risk. Since publishing Vigil, I have written many commentaries and given many talks criticizing the crackdown. And after having had some interactions with activists who have been sentenced to prison, I have had even more interactions of late with activists who have headed into exile, in some cases ending up with bounties on their heads. The CCP cares more about those interactions, I suspect, than about what I say and write.

Would any of this have consequences? There’s no way to know. I feel, though, that there might be some danger in going to Hong Kong, probably not for me but perhaps for friends there I would want to see. And Hong Kong is the part of the PRC to which I most want to return. Feeling even a vague sense of unease about going there makes me ambivalent about traveling to any part of it.

I have the luxury of being at a career stage where I do not need to go. My current projects can be researched elsewhere. I have no family in the PRC. Many of my friends there have left. I can thus be at peace with the idea that the break from trips to the PRC that began when I was in my late 50s could easily last through my 60s and beyond.

And yet, I am glad that many friends and students have headed to the PRC or are planning to go there. I like hearing about their experiences.

When Harris selected Walz as her running mate, it was fascinating to discover when reading up on him that he was the CEEC member at the 2014 hearing who impressed me the most. I remembered his remarks and questions but not the name of the person responsible for them.

It feels right to me to not go to the PRC. But I believe it is useful—even in times when the CCP is moving in a disturbing direction and even when, perhaps especially when, relations between Beijing and Washington are tense—for people to strive to keep lines of communication open and minimize sources of misunderstanding.

This makes it easy to know what I’ll do if I encounter any 25-year-olds who describe facing dilemmas like the one Walz did at their age. If they tell me their impulse is to make the same call that he made in 1989, I’ll tell them I support their decision.