You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

robynmac/iStock/Getty Images Plus

“It is not obvious that knowledge is closeness.”

—Alan Lightman, Einstein’s Dreams

Late 1990s, Barcelona: a new student looks about Edifici Jaume I of the Universitat Pompeu Fabra for an art theory seminar to be taught in Spanish rather than Catalan.

“On és l’aula 302?” he asks a woman by the humanities bulletin board.

“Està aquí.” She motions with her head. “Sóc Estela, la professora,” she says, extending her hand.

That day, Professor Ocampo laid out the semester. Each student was to write an essay and conduct a 90-minute session on a single artist. Next to my name on the list was “Henry Moore.” That was the extent of the instructions.

This first experience outside the over-rubricized environment of U.S. higher education confounded me. What are the expectations? How long are the essays? What materials should be analyzed? What citation system? In 90 minutes, will there be a break? How will this be graded?

That fall, I discovered an educational backdrop unlike what I had experienced at Brandeis University and Boston College. I had to create everything myself—the rules, the sources, the ideas, the voices, the analyses, the style, the delivery. The attendant anxiety made the scholarship my own. I gained an expertise that was perhaps possible in my previous environment but came upon me suddenly and positively in Barcelona through the ambiguity of the assignment.

As a method to fill 90 minutes, I made handouts (it was the 1990s) and compared Moore’s work to music, movies, languages, places and food. I began this as an experiment but soon discovered the strategy opened new questions and contexts. Moving inquiries from images to words to ceremony and consumption involved language shifts and that led to further questions: How do critics discuss Moore’s art and biography differently in Catalan, English and Spanish?

My uncertainty that day eventually led me to better questions: How can students become what they study? What pedagogies facilitate self-integration, a process in which students combine what they learn with who they are? How can an assignment bring students closer to their education, to the material they analyze, to participate in it, to live through it and to experience their knowledge holistically?

By contrast, conventional U.S.-style rubrics presume too much, set narrow boundaries and reward non-transformative exploration. While such mechanical demands are contrary to some of the best parts of knowledge development, the normalization of their use distorts and divides ingenuity into blunt categorization.

In a sense, rubrics provide students with something largely useless: a clear understanding of what is expected of them. While clear expectations may seem beneficial, the fact is they rarely exist in academic or professional writing (or life, for that matter). Fostering students through them cedes an opportunity for budding scholars to create arguments and forms of expression highlighting nuance unknown to the rubric (and its author[s]). Such moments are when authorship itself—or the process of developing personal authority on a topic—can be developed.

But there are some conventional reasons to use them: They give students confidence and allow them to set goals. They link writing and content to grades. They allow instructors to give more informed feedback. “They want a very specific road map,” Jonikka Charlton, senior vice provost at University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, said of undergraduates. “They want to know exactly what they need to do to be successful in the course, but they want to put in the minimum amount to sort of check the box. ‘I did this assignment. I did the thing I have to do.’ And that’s it. ‘I’ve given all I have to give.’”

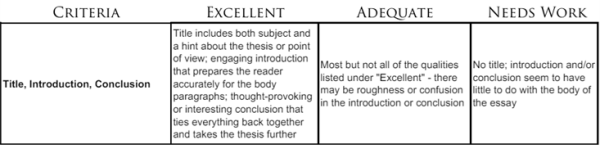

A sample essay grading rubric from the University of Michigan frames expectations:

University of Michigan

The above is excerpted from a table with eight rows. If some argue rubrics like this can be useful to assess if students acquire knowledge, the ability to apply experience and knowledge in different ways across contexts is often more important and beyond their measure. Some of the failures of standards-based education emerge in the rubricization of assignments that overstructure and constrain student exploration. Rubric logic maintains that structure is more important than content and experience. Meanwhile, an important aim in humanistic writing is to transcend preset values.

An evaluation system like this provincializes knowledge, hardening its borders.

A rubric cannot ask students, what do you know that is missing from existing research? What is your relationship with that knowledge? How does your community develop it? What role does it have in your life and education? Why is your knowledge absent?

Confidence in rubrics creates a gaze that looks down on knowledge. Beauty is what the rubric defines, what the rubric feels, what the rubric allows. This beauty is contingent, often ugly.

So-called vague instructions ask students to create perspectives and the tools to share them. This departure from rubric-based learning is often what students require—and it can transform pressure into playful and creative energy, encouraging students to become writers, to rule their own material and to give meaning to the knowledge they create.

Abandoning rubric-based learning modes asks students to:

- Examine a question from your own view and

- Rehearse verbal reasoning with an argumentative structure of your own design.

These ends are useful across disciplines but also formative experiences in scholarly growth.

While I sympathize with efforts to meet students’ needs, creating bounded evaluation is not a path to intellectual liberation. When students recognize themselves as co-legislators of knowledge, their education may turn toward generation of new perspectives about experiences and about their own voices. Such approaches challenge students to ask questions about how they and other scholars presume the world has order.

An antirubric stance reaches through and beyond pedagogy, turning student experience away from structured outcomes and measurements, toward multivocal and multiform narration that can legitimately approach the underpinnings of what Antonio Gramsci envisioned for organic intellectuals: Scholars who do not merely carry or replicate the values of their people but actively help to re-form them through reflection, thought, writing, presenting and other forms of sharing and participating.