You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed|Getty Images

We all know the story of rigor: “Rigor is how we prepare students for the real world, and our job as faculty is to bring rigor to our classes.” In this story, rigor is the hero and faculty members are its enforcers.

The story of rigor is an example of a stock story, a narrative told over and over again that teaches and reinforces one view of reality. Stock stories provide a simple view of the world, told from a singular, dominant perspective, one that obscures other, messier and more complex realities.

Rigor, according to this stock story, is core to the very existence of higher education, because it enables us to determine who is worthy. We have all heard some version of this sentiment: “To be of value, a course must be rigorous.” In other words, a course is of value only if it is hard enough to enable us to rank-order the students. Higher education serves as a gateway to opportunity, and rigor is how we determine who can pass through the gate.

And students are not the only ones being subjected to rigor-informed judgment—faculty members are as well. “She gets good student evaluations only because her courses aren’t rigorous.” In my experience, this critique is more often aimed at faculty not on the tenure track or assistant professors who some colleagues think do not belong.

As a neurobiologist and an educator guided by a science of learning framework, I do not dispute that rigor can play a role in learning. The role of rigor, however, is misrepresented by this stock story—so much so that Jordynn Jack and Viji Sathy make a strong case for no longer using the word “rigor” in conversations about higher education. The misrepresentation of rigor becomes clear if we move past the dominant stock story of rigor to acknowledge and examine the messier reality it conceals.

Learning (not rigor) is what prepares students for the real world, and our job as faculty members is to strategically challenge our students and help them engage with that challenge to enable their learning. In this concealed story, learning is the hero of higher education and faculty members are its facilitators, while rigor for the sake of rigor is the antihero.

Learning happens when the learner directs their neural attention system toward a cognitive challenge and engages with that challenge in a manner that results in consolidation of the new learning. This creates representative neural circuits that can be further strengthened through continued use of what was learned. To the extent that we align cognitive challenges with course learning outcomes and assessments, all students have an opportunity to learn and to demonstrate their learning.

Not all challenges, however, serve to promote learning. A course or curriculum can be rigorous in ways that have little to do with learning (some of which are detailed by Kevin Gannon): give assessments that do not align with what was actually taught in the course, test students on a small sample of a massive amount of material, provide no feedback along the way to a single high-stakes assessment, enforce inflexible deadlines and time constraints, include requirements for no good reason, and be sure to let students know that they do not really belong in the course or in the major (“If you don’t do well in this course, you probably shouldn’t be in science”).

Anything that makes a course harder for at least some students makes that course more rigorous, whether or not those challenges actually support learning. This sort of rigor is much like riddles told by storied gatekeepers such as the Sphinx of Thebes— arbitrary barriers that support the myth of meritocracy by giving the gatekeeper an irrelevant reason to let only a chosen few pass. Rigor in the form of arbitrary barriers does not support learning, and arbitrary barriers are detrimental to student well-being.

The stock story of rigor holds that a course is rigorous if enough students fail or withdraw, regardless of the reasons. When not enough students fail, we hear complaints from the most vigorous defenders of rigor about grade inflation and comments like this: “If no students failed, then it obviously wasn’t a rigorous class.” It is critical to the gateway function of higher education that some students fail and that their failure is documented on the transcript.

Using student failure as a measure of rigor assumes that some win only if others lose, thereby reinforcing the value of competition. But the amount of learning in a class or curriculum is unlimited, so why should it be competitive? Earning a grade is competitive only if faculty are meant to be gatekeepers (defenders of rigor) rather than educators (facilitators of learning). Faculty should be allowed to be educators, to carefully design appropriately challenging courses and practice pedagogies of care, enabling all of our students to learn.

Another messy reality is that the gradations inherent in grades (it’s right there in the name) do not reliably indicate who learned more and who learned less, nor do grades indicate which students will retain their learning beyond the end of finals week. A premed student once told me that they missed a course grade by one point out of 1,000 in a class—a 0.1 percent determination of how well they had learned compared to other students. We do not have that degree of accuracy in measuring learning, yet final course grades and transcripts give the power to pretend as much.

A simple letter grade on a transcript cannot tell us why the grade is what it is or the story of how it came to be. What role did life events play? Was the student working long hours, struggling through stereotype threat, learning and communicating in a nonnative language, dealing with relationship drama, caring for a sick parent, or facing their own health issues? How did life impact their grade? External influences on individual student academic performance cannot be measured reliably, so we ignore them—or perhaps try to mitigate students’ challenges as best we can (e.g., through flexible deadlines). Then we post a simple grade as a far-too-oversimplified summary that cannot accurately reveal what a student experienced and learned in our course.

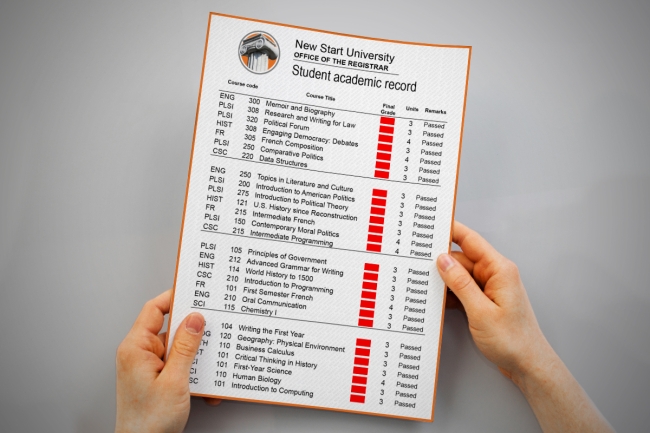

The letter grades we post then become part of a transcript that a student may be required to share with a desired graduate or professional program or employer. The transcripts that higher education creates not only list accomplishments but also document failures in a permanent manner: our transcripts are academic rap sheets.

We can do better.

We can reject rigor for the sake of rigor as nothing more than traditional gatekeeping: stop rewarding faculty members for high course failure rates and stop stigmatizing faculty for high learning rates.

We can write a transformative story for all of higher education by committing individually and institutionally to 1) course and curricular design that incorporates challenges appropriate to learning, 2) courses and classrooms transformed through pedagogies of care (e.g., inclusive teaching, trauma-informed pedagogy), and 3) the elimination of policies and practices that create arbitrary barriers to student success.

Finally, we can turn transcripts into records of achievement rather than rap sheets. In a brighter, more equitable future, I envision a transcript that lists courses completed successfully (no letter grades) and degrees earned. This reimagined transcript—let’s call it the achievement report—will organize student accomplishments by area of study rather than chronologically, because the topic matters more than the term of completion. The achievement report will indicate not just course titles, but also which courses emphasized specific skill sets that employers highlight as being desirable, such as communication, problem-solving, teamwork and creativity.

Replacing the rap sheet version of a transcript with an achievement report that emphasizes students’ academic accomplishments will require leadership in institutions of higher education across the U.S. But if we truly want to support student learning and well-being, we will find a way to demonstrate what a student has learned and not where they stumbled. In doing so, we will help our students succeed both during their college journey and after they graduate.