You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

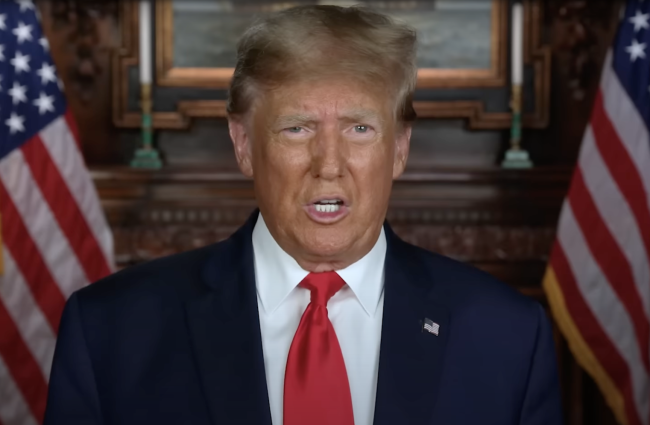

Former president and current Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump recently vowed to “fire the radical left accreditors.”

YouTube

Accreditation is at the heart of American higher education, but it’s rarely in the headlines, and it almost certainly has never been an issue in a presidential campaign. But we live in unpredictable times, when former president (and current presidential candidate) Donald Trump has already trained his fire on accreditation agencies, as has Trump’s most prominent challenger for the GOP nomination, Florida governor Ron DeSantis. Trump recently vowed that he will “fire the radical left accreditors that have allowed our colleges to become dominated by Marxists, maniacs and lunatics.”

It’s not known what Trump would replace accreditors with. But it is clear that this attack on accreditors is part of a broader assault on diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives in an effort to appeal to the Republican Party’s populist base. It is just one more way that colleges and universities find themselves uncomfortably on the front lines of the culture wars. Still, Trump is the leading candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, and it’s worth taking a closer look at what it would mean to “fire” accreditors.

Some background: to participate in federal student aid programs, institutions of higher education must be accredited by an accrediting agency that is recognized by the secretary of education as a reliable authority on educational quality. The requirement first emerged as part of the Korean War GI Bill and has been a central feature of federal higher education policy for more than seven decades. At present, about 50 organizations perform this function for the government, with most traditional nonprofit institutions overseen by regional accreditors.

Accreditors can be “fired,” but not with the suddenness or drama of a reality TV show. The education secretary can take action to “limit, suspend or terminate” an agency that the secretary believes is failing, but only after giving the agency the opportunity to challenge the action. And, as with anything federal agencies do that has high stakes, lawyers and courts are usually involved.

This means that terminating or firing an agency takes a long time. In the case of the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools (ACICS), for example, one of the few accreditors to ever be fired, it took the government six years over three presidential administrations to dismiss an agency that was manifestly failing. It was a process that (irony alert) the Trump administration formally blocked for several years.

Accrediting agencies perform a wide range of functions for colleges and universities, but as far as the federal government is concerned, accreditors are designed to ensure that colleges offer high-quality education and training and that the interests of students and taxpayers are protected. Using accrediting agencies as quality-control agents means that institutions are examined by a third party and are not evaluated by the U.S. Department of Education.

Established, successful quality-control mechanisms in any industry may not be perfect, but they usually serve a vital public purpose. Take them away without a careful, well-thought-out alternative and bad stuff will happen. If the Food Safety and Inspection Service at the Department of Agriculture was suddenly “fired,” for example, we’d see a sudden and dramatic increase in cases of food-borne illness. Dismantle the Food and Drug Administration, and the safety and efficiency of the nation’s drug supply would quickly decline. Kill off state bar exams that determine who is allowed to practice law and, well, never mind.

There is no ready alternative to fill the role played by accreditors. Most state governments rely on accreditors to ensure the academic quality of postsecondary institutions rather than attempt to evaluate academic programs. The U.S. Department of Education lacks the expertise, staff and legal authority to fill the void.

Could other organizations become accreditors? In theory, but not easily. Federal law mandates that before an organization can act as an accreditor under the Higher Education Act, it must have successful, demonstrated expertise as an accreditor.

But there is an even more fundamental rub. While the Higher Education Act identifies a list of 10 broad areas where accreditors must have standards (e.g. curricula, faculty and student support services), federal law clearly and unambiguously prohibits the federal government from imposing, approving or dictating the specific academic and programmatic standards of accrediting agencies. In other words, if an accrediting agency wants to establish a diversity, equity and inclusion standard, it can do so.

Moreover, the Department of Education Authorization Act, which created the agency in 1979, clearly blocks the department from exercising any direction, supervision or control over the academic program of “any accrediting agency or association” unless otherwise permitted by law. By directly singling out accreditation agencies, Congress made clear that the department must take a hands-off approach to their standards.

There is, of course, a solid public policy reason to prohibit the federal government from dictating accreditation standards. If one political party can impose or prohibit standards for accrediting agencies, it certainly allows that the other party has the right to do the same thing when the political winds shift. In the process, accreditors and institutions could easily find themselves subject to a continuous change in their standards to satisfy the whims of whichever party happens to be in power.

In fact, multiple federal laws prohibit the federal government from reaching capriciously into the academic programs of accrediting agencies. Providing some distance between campus practices and government overseers has allowed the United States to maintain its large, diverse network of institutions, and it’s one more reason why U.S. higher education continues to be the envy of the world.

This does not mean that the accreditors are above criticism or that their work cannot and should not be carefully and frequently reviewed. To the contrary, the federal government has clear authority to review their work, and all accrediting agencies are regularly subjected to a stringent renewal process. Nor does it mean that the federal law that governs what accreditors do cannot or should not be changed as times and circumstances change. But current federal law clearly forbids federal officials from prohibiting or imposing accreditation standards.

This, of course, assumes that the administration in power is willing to follow the law. If an administration—any administration of either party—elects to ignore the law and plunge ahead with sharp departures in public policy, then all bets are off. Stay tuned.