You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

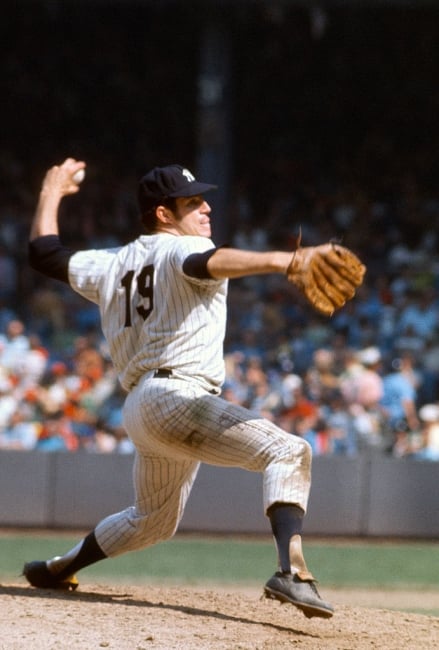

Fritz Peterson, one half of the wife- (and family-) swapping Yankee pair, pitching in 1972.

Focus on Sport/Contributor/Getty Images Sport/Getty Images North America

As we enter June, sports fans will soon stop hyperventilating. Months of Stanley Cup and NBA playoffs will mercifully yield champions. After that, it’s just baseball, the only professional sport that runs at summer pace.

Summer’s most successful team is undoubtedly the New York Yankees, having captured the World Series 27 times in the last century. As a Toronto Blue Jays loyalist, it pains me to write this. In the only major American professional sport without a salary cap, the Yankees always had more money than most other teams—unseemly and unsporting. My view hardened the first time I set foot in Yankee Stadium. We sat in the upper deck and, from the fifth inning on, dodged fight after fight, most instigated by one bald beer-toting fan my history-major roommate affectionately dubbed “Germany.” Sensing my shock, after the conclusion of beer, baseball and brawls (in that order), my roommate guided me down to visit Monument Park, where Yankee greats like Ruth, Mantle and DiMaggio are honored in bronze and stone.

Here are two names you won’t find in Monument Park: Mike Kekich and Fritz Peterson. Not only because Kekich never made an All-Star team and Peterson just one, but because 50 years ago, at the start of the 1973 season, the two New York Yankees starting pitchers announced they had swapped wives. Actually, Kekich and Peterson swapped more than wives. They swapped entire families, including dogs. Thurman Munson, Yankees captain from 1976 to 1979, did his best to defend his teammates: “Everyone knows we’re a bunch of crazy guys.” Yankees general manager Lee MacPhail half joked that the Yankees “may have to call off Family Day.”

The early ’70s were a strange time. But 50 years on, swapping’s still going on. It’s apparent every time I open my mailbox. While most of the thick-paper wish books and elaborate mailers addressed to my son Leo, who completes his junior year of high school next week, come from private universities and liberal arts colleges, a surprising number extol the virtues of public flagships like the University of Florida, the University of Michigan, Texas A&M University, the University of Virginia and the University of Washington. Leo’s received something from most flagships with one notable exception: our home state of California. Which leads to the inescapable conclusion that what these universities mainly see is an out-of-state applicant.

It’s not only mail. According to an analysis by Third Way, public research university admissions officers visit more out-of-state high schools than in-state. Third Way identified seven public research universities that made twice as many out-of-state as in-state visits. And the schools they’re visiting tend to be private schools and publics in the wealthiest neighborhoods.

There are two reasons out-of-state students have become more important for flagships. First, budget cuts. According to last week’s annual report from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, 2022 marked the first rebound of state support of higher education past inflation-adjusted 2008 levels. The caveat is that’s the per-student metric, and the denominator is down by more than a million from its peak in 2011. In aggregate, 28 states invest less in public colleges and universities than they did 15 years ago.

Second, while state political leaders keep a close watch on in-state tuition, there’s no constituency for controlling out-of-state tuition, making it a Yankee Stadium free-for-all. As a result, flagships charge out-of-state students $20,000 more on average—a gap that ranges from a high of $38,000 (University of Michigan, followed closely by Virginia; California, Berkeley; and Wisconsin at Madison) to $15,000 (the University of Wyoming, noting that the differential in both Dakotas is anomalously less than $5,000).

Last fall, Aaron Klein of the Brookings Institution published “The Great Student Swap,” an authoritative look at how state flagships have been raiding each other’s rich kids. Over the past 20 years, 48 of 50 flagships grew their share of out-of-state students; the average increase is an eye-watering 55 percent. As a result, Michigan is now 48 percent out-of-state, Colorado at Boulder 44 percent, Madison 40 percent. The list goes on …

While there are innumerable problems with family swapping, student swapping has at least five:

- Flagships don’t have room for everyone. When flagships seat a party of wealthy Californians, there’s nowhere for locals to eat (and even more people hate Californians). The corollary of increasing out-of-state enrollment is fewer spots for in-state students. Across public flagships, Klein found an average decline in the share of in-state students of 15 percent between the first-year classes of 2002 and 2018, and five states had a decline of more than 20 percent. At the University of Alabama, the share of in-state enrollment has fallen by half. This might be fine if no in-state students wanted to enroll, but that couldn’t be further from the truth; Americans seem to have woken up to the fact that flagships that play faster sports than baseball on national television are better brands than all but a small handful of privates.

The coming of comfortable carpetbaggers changes campus composition. The Jack Kent Cooke Foundation reported average family income at the University of Michigan to be $200,000 in 2014, or about four times that of the average Michigander. The Hechinger Report found 15 flagships with a gap of 10 percentage points or more between the percentages of Black public high school graduates in their states and Black freshmen enrolled.

And student swapping filters down from flagships. Within the University of Wisconsin system, out-of-state enrollment has grown 63 percent in the past decade, while in-state enrollment has decreased by 20 percent. Crowded out, at-risk students leave to dine at places where they’re less likely to complete their meal and more likely to get sick.

- Changing flagships for the worse. While Michigan may still be a serious place, a Jack Kent Cooke Foundation report argues that when “less prestigious public flagship universities” enroll more rich kids with weaker academic records who “view college life as a continuing party,” the academic climate takes a turn for the worse. Students who don’t fit this profile “feel unwelcome for their academic effort and socially excluded for their lack of money.” So, in addition to taking up scarce seats, the Great Student Swap may contribute to depressed completion rates for the students states should care about most. If the Supreme Court ends affirmative action this month, it could end up being a rounding error relative to harm already inflicted from student swapping.

- Reducing state support. Another problem is reduced political support for state funding. In 2015, Ozan Jaquette and Bradley R. Curs found a strong negative correlation between out-of-state enrollment and state support. As Klein observes, this chicken-and-egg affair could go both ways: declining state support could force flagships to enroll more out-of-state students. Or enrolling more out-of-state students could reduce political support for public colleges. It’s likely a bit of both—a state-school death spiral.

- Increasing student debt. As students eschew their own state schools for flagships in other states, many are spending (and often borrowing) three to four times more than they would have otherwise paid, likely for a comparable education. Klein took a close look at 16 flagships and calculated $57 billion in excess tuition costs from 2002 through 2018. Student swapping is America’s most expensive game of musical chairs.

- Not everyone swaps equally. Some flagships are more equal than others. West Virginia University competes hard in this game—yet another flagship with an out-of-state majority. But WVU needs to keep drawing wealthy students to north-central West Virginia, which isn’t for everyone, as demonstrated by projected continued enrollment declines and fiscal havoc. So for a handful of flagships, musical chairs may be more like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Is it possible to stop the swapping? Attentive states have employed three strategies:

- Stop it before it starts. Two major flagships have sensibly refrained from mailing a paper monstrosity to Leo. The first is the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, which has consistently maintained 82 percent undergraduate in-state enrollment. How’s that possible? Because the system mandates it. In 1986, the system board capped out-of-state enrollment at 18 percent. If the flagship exceeds 18 percent, it effectively gets fined by the system. So caps can work, except when they’re Rocky Mountain High (CU Boulder’s cap on out-of-state undergraduates is 45 percent), or when a flagship is capable of convincing state legislators or system regents to remove it (UW Madison, where out-of-state enrollments have doubled in a decade).

- Give in-state students a chance. The other flagship that failed to make an appearance in our mailbox is the University of Texas at Austin. UT remains around 90 percent in-state because state law requires it to admit the top 6 percent of graduates from Texas high schools. This is the anachronistically named “Top 10 percent law” (it was 10 percent when the law was passed in 1997, now 6 percent).

- Bribe ’em. The third strategy is to throw money at the problem. California promised additional funding for the University of California system as long as in-state enrollment goes up and to the right. Based on the numbers—5 percent more funding each year in return for 1 percent in-state enrollment growth—it appears UC got a great deal. Of course, beyond a vague commitment to “implement strategies that increase the overall affordability of on-campus housing,” UC didn’t promise to find the new students a place to live. That’s an additional charge.

If you’ve read this far, it’s undoubtedly to learn what happened to the family-swapping Yankees. As mentioned, not everyone swaps equally. While Fritz Peterson and Susanne Kekich lived happily ever after, Mike Kekich got the wrong end of the trade. He soon broke up with Marilyn Peterson and was traded to Cleveland. Then, to add insult to injury, he lost his Cleveland roster spot and went off to pitch in Japan. Who replaced him on the Cleveland pitching staff? Peterson, living with Kekich’s family. Decades later, Kekich remained so bitter about the whole thing that he refused to cooperate with a Matt Damon and Ben Affleck film—The Trade—stalling the project indefinitely, to the detriment of swapping scholars.

There are two major drawbacks to swapping. First, it’s scandalous. Second, it doesn’t work. And for flagships, it’s probably going to get worse. Last week, Bain released a dire financial forecast for America’s colleges and universities, exempting only the most highly selective privates. Bain had this to say about large public universities: “While we do not expect them to fail given their scale, public support and options for cutting costs and generating new revenue, we do expect many will need to make foundational changes to offset potential deficits.”

Here’s one foundational change: dramatically expand capacity. The flagships have been growing undergraduate enrollment, but have not kept up with the growth in the number of high school graduates. And that’s not nearly enough when everyone and his brother wants to attend. As a result, as Urban Institute’s Tomás Monarrez told The Hechinger Report, many flagships are “behaving basically like an Ivy League institution when it comes to admissions.”

Why aren’t flagships creating more seats? While not technically a flagship, under the leadership of President Michael Crow, Arizona State University has taken up the mantle of America’s most innovative university. By adding or expanding campuses and schools, Crow has grown on-campus enrollment 43 percent. Meanwhile, ASU attracts more National Merit Scholars than all but four flagships. Success has fed on success as donors want to be part of the ASU story, funding additional growth. By adding capacity, flagships can generate more in-state revenue, excitement, philanthropy and perhaps state appropriations, thereby reducing the need for swapping for universities and ultimately applicants. Expansion is the only no-regrets swap-stopping strategy.

Swapping rich kids is a crutch keeping flagships from fulfilling their missions and serving their states. It’s not only time for the swapping to stop—’tis also the season. As a result of a series of rule changes, Major League Baseball is a lot less languid than it used to be. And if America’s pastime can change, less-than-agile flagships can do the same as long as they put their heart into it.

Whether they’ll put their heart into it is hard to say; I’m no Joan Quigley, or even Thurman Munson. I suppose at the end of the day, the heart wants what the heart wants. Which is OK as long as what the heart wants isn’t a teammate’s wife and family.