You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

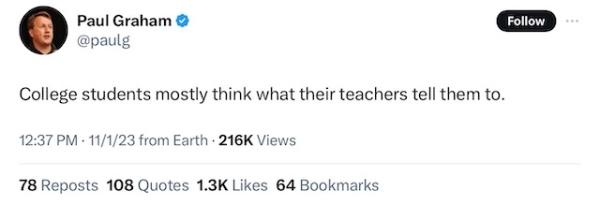

There is little that irritates me more than a prominent person confidently claiming that college students are just being brainwashed by their instructors.

This recent example from tech founder/investor Paul Graham caught my eye.

John Warner

Anyone who has spent any time as a student or instructor knows that what Graham says here is not true. College students come to their institutions with well-formed belief systems, and research into these things suggests that to the extent that students do change their beliefs while in college, the most important influence is not their professors, but their peers.

Now, there are kernels of truth under Graham’s statement. I think anyone who has been a student has perhaps grooved a particular assignment to the known preferences of an instructor—I’ve done this, anyway, starting back in high school—but that doesn’t mean the student has been told what to think in the larger sense Graham means it. It’s a temporary performance to earn a higher grade.

So yes, this is B.S. meant to discredit both the opinions of students and the legitimacy of higher education, but it’s also very old news and this charge will never ever go away. This is me writing about this very thing back when I was still guesting at Oronte Churm’s blog space. It’s almost not worth pushing back against, which is why I want to pivot to the thing I came here to say to this audience inside higher education.

I think it is a mistake to respond to the charge that faculty are brainwashing students with responses such as, “Brainwash them? I can’t even get them to read the syllabus!”

I get this response. I’m sure I’ve said it or something very close to it, but I also have come to believe it’s counterproductive, even as there is some truth to it. I say this because I think it is important to own up to the fact that for many of us, the mission of teaching involves challenging students’ knowledge and perception of the world in a way that may indeed cause them to think differently.

At least that’s what I’ve always tried to do. I want to do my best to challenge a student’s critical sensibilities while also providing them experiences that allow them to understand their critical sensibilities, and more importantly, how to express their views to the world in an impactful way.

This is not brainwashing or inducing students to think the same things I do. It is rather an unavoidable by-product doing the work of educating students.

One reason the “I can’t even get students to read the syllabus” quip now hits me wrong is because it tags all students with a problem behavior that’s not universally true. Additionally, when you get right down to it, in the grand scheme of things, it’s not that important. It’s a behavior, a behavior learned over time that is actually quite easily redirected.

More importantly, it is an at least tacit admission that what we are doing as instructors doesn’t matter because we are powerless against student apathy/indifference or whatever else. I don’t believe this is true, certainly not on a broad scale. If it was, I would stop caring about the things I care about, because the battle would be lost.

I will proudly admit that I want to change how students think about writing. For those who see writing as a pro forma exercise done by following a template for a grade, I want to change their attitudes to see writing as a fundamental tool for thinking and the acquisition of knowledge. For those who fear trying something unfamiliar because of the risk of a less-than-ideal outcome, I want them to see that failure in writing is our greatest teacher and easily survivable.

Denying that I want to shape how students think is to deny some essential part of what I see as the instructor’s role in education. But this is much different from telling students what to think. The goal is to provide students experiences and feedback that helps them figure out where they stand for themselves.

I offer process, not prescriptions, and like the overwhelming majority of people who teach in higher education, I have a high tolerance for differing viewpoints, particularly when they are sincerely held and well-evidenced.

Inevitably some of my attitudes and beliefs may rub off, but if that’s the case, it’s only because they’re also meaningful to the student. I’m sure all of us who teach can think of a professor or three whose thinking has left a permanent imprint on us.

Or not. I kept one of my college notebooks from a particularly unsatisfactory literature course where I was convinced the professor was trying to torture me with the way he spoke about books. Only later did I realize that he was a dedicated new critic, a sensibility that just doesn’t resonate with me.

Or maybe it’s a temporary imprint that once faded leaves behind something more permanent. At the beginning of my M.F.A. program, I swallowed the philosophy of my mentoring professor whole hog because I looked at his success and thought that he must have figured out the key to unlock the good stuff.

He had … for himself. For me, the next three years were spent figuring out the ways what worked for me differed from what I’d been told. Coming out the other side of that experience was not easy or always pleasant, but it has shaped my attitude toward received wisdom ever since, a stance that has pretty much become my professional stock in trade. I can’t imagine a more valuable educational experience.

For sure, we shouldn’t stand back and accept that charge that professors are overwhelmingly in the business of brainwashing students, but neither should we discount the depth and importance of the work of education. The nuances of this are tough to explain next to the pith of statements like Graham’s or the return pith of “I can’t even get them to read the syllabus,” but it’s a long game, so we might as well play it as best we can.