You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

While many associate professors experience frustration at midcareer, these experiences vary for faculty of differing races and ethnicities. Diversity is a key issue in higher education and many efforts focus on recruiting faculty of color. Fewer initiatives consider how to ensure that diverse faculty members thrive and are retained, although retention and promotion is clearly another piece of the puzzle.

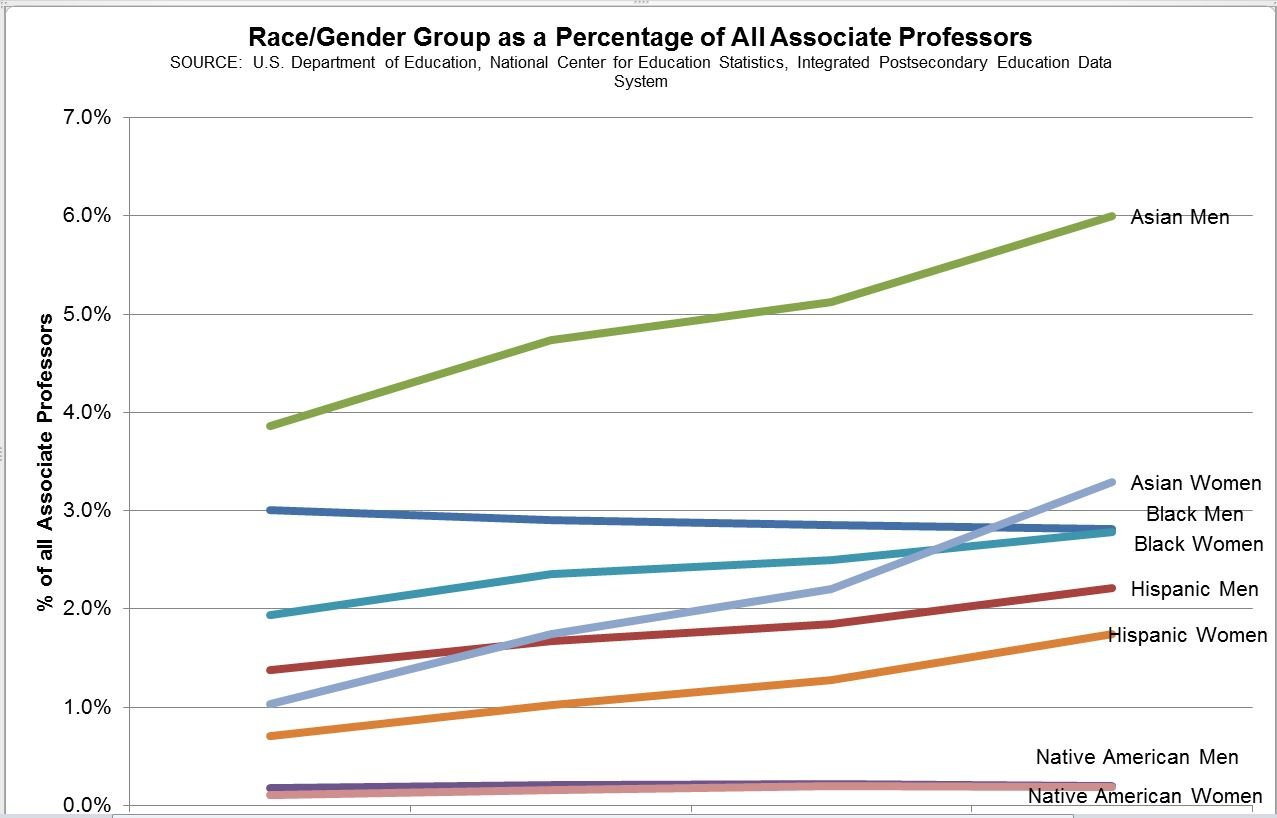

According to the data available from the National Center for Education Statistics, faculty members of color make up a very small percentage of all associate professors. As the figure suggests, Asian men have made the most notable progress over this time period; while Asian women are less well represented, they have made progress since 2005. Black men, who were not far behind Asian men in 1995, have lost ground. Native American associates have made no progress, and progress is slow for black women, Hispanic men and Hispanic women.

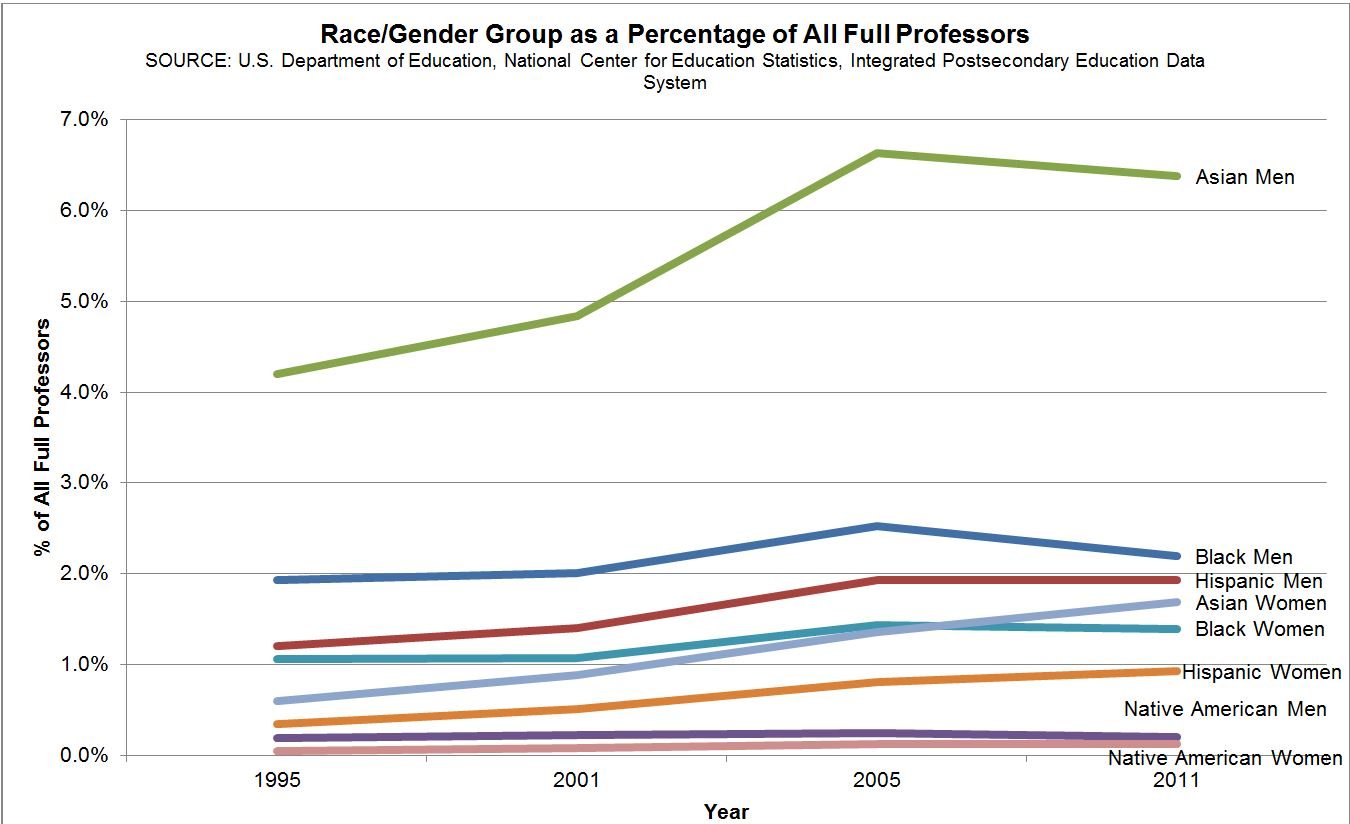

While these numbers are low, they are more distressing when compared to change over time for full professors. If faculty of color were moving through the ranks, we should expect to see change in the composition of full professors. Yet most groups have barely increased their representation among full professors. Asian men’s gains at the full level have recently slowed, despite their steady increase among associate faculty. Native American men and women, black men and women, and Latinos also have stalled. Only Asian and Latina women continue to make gains, and these are slight.

These issues are not simply about the missing numbers of Ph.D.s of color; a larger proportion of Ph.D.s of color than white Ph.D.s leave academe at every turning point. What makes it difficult for faculty members of color to be promoted?

In a recent publication, Mari Castañeda and Michael Hames-García reflect on these issues. Faculty members of color face challenges in convincing their colleagues that their scholarly record merits promotion. Implicit bias, or unconscious assumptions that minorities are less qualified, often discussed with regard to faculty hiring, also operates in faculty promotion. Institutional racism can work against faculty of color, making tenure and promotion processes feel like running the gauntlet. It can be challenging to find external letter writers knowledgeable about the intellectual contributions that faculty of color make. Castañeda and Hames-García note this is particularly challenging for faculty members who focus on issues of race, ethnicity and gender in their scholarship.

Even when faculty members of color win tenure successfully, some may have experienced a lack of support, microaggressions or outright discrimination in their bid for tenure. Among these faculty members, the most successful often leave their institutions, while those who stay feel alienated and may experience “psychological departure.” These issues are particularly pronounced in predominantly white institutions.

Associate professors of color, particularly black, Latino and Native American faculty members, also may find themselves condescended to and otherwise made to feel that they do not belong. This can even include being threatened, profiled by the police and arrested. For example, Kiese Laymon wrote a powerful essay about his experience at Vassar College that describes the police profiling he and his brown and black students have been subjected to, as well as a wide range of aggressive and unconscionable behaviors from his colleagues, who questioned his every accomplishment. Eve Dunbar similarly describes the constant hazing she experienced as an African-American woman. These challenging conditions help explain lower retention rates for midcareer faculty of color.

To advance to full, faculty members of color may again be required to achieve even more than white colleagues. Faculty members of color who excel may also have to work harder to assuage the feelings of white colleagues. One faculty member noted that both students and colleagues seem not to recognize his achievements and appear to see him differently from white faculty at the same career stage. Another faculty member described how despite her exceptional record of funding and publication, she was not promoted because two white men hired before her would “feel bad” if she were promoted first.

Indeed, faculty members of color have, at times, successfully sued, given evidence that the handling of their cases differed from white colleagues who were promoted. One such example is Lulu Sun, a professor of English at University of Massachusetts at Dartmouth; the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination ruled that Sun, a woman of Taiwanese origin, had been held to different standards from white men considered for promotion at the same time, ordering $200,000 in damages, back pay and promotion. Problems with advancement can also limit opportunities for faculty of color to move into central administrative positions, where they might play key roles, both in shaping the larger trajectory of the institution and creating support for diversity.

Political events can also make it challenging for faculty members of color to remain focused on their goals. Faculty of color may feel disconnected from their communities of origin and feel selfish about focusing on their research or careers given larger struggles. As Kerry Ann Rockquemore notes, there are many different ways to respond to larger political events, including engaging in protests, developing or participating in on-campus or community panels, bringing current events into teaching, writing op-eds and blog posts, or shifting research projects around to address pressing societal issues. Yet as Rockquemore further argues, faculty of color may also experience chronic stress, and may need to develop strategies to support their emotional exhaustion at these moments. Indeed, given the microaggressions and pure aggressions many faculty of color face, radical self-care is crucial to long-term survival.

Another central issue minority faculty members face is their increased commitment to promoting diversity on their campuses, as well as engaging in the larger community. Within the university, this work might include mentoring students, working with student groups and providing informal mentoring to students and other faculty. Faculty members of color often engage in this work as part of a political commitment, to change the academy and make it more welcoming. These faculty members may also design research and teaching that engages and betters local communities because of their commitment to broader social change. Yet this work often goes unrecognized and unrewarded.

A number of institutions, including our own, have adopted policies aimed at rewarding faculty for making contributions to diversity. For example, University of California at Berkeley faculty members can be nominated for the Chancellor’s Award for Advancing Institutional Excellence for a wide variety of work, including innovative research, mentoring of underrepresented groups, creating curricula that develop intercultural competence, engaging in service that advances principles of equity and inclusion, and the like. Although the primary criterion for tenure and promotion at most research universities is still research, first and foremost, awards like this at least assign a publicly recognized value to the service in which faculty of color are more likely to engage. Universities may also develop alternative paths to full that recognize the importance of public engagement and leadership.

In trying to diversify, many universities unintentionally place higher service burdens on their faculty. At our university, which has historically aimed for diverse committees, faculty members of color noted that they were particularly hard hit. In one focus group, a participant stated, “I’ll just say it: we need a person of color on the committee.” Another faculty member responded, “I get the same thing, the female Hispanic.” While our university has attempted to address these inequalities in service, there are no easy solutions to the need for diverse perspectives and mentoring in predominantly white universities.

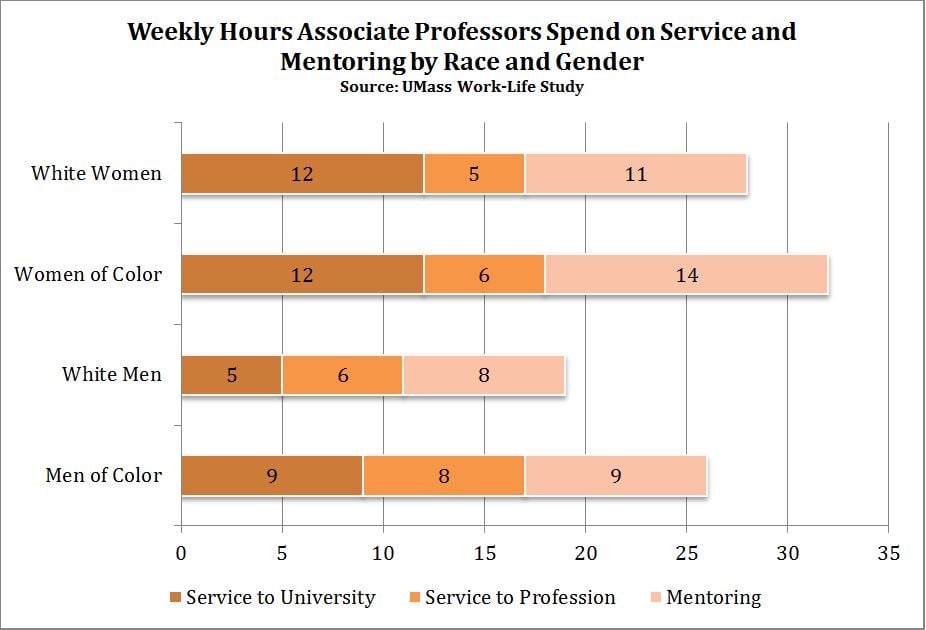

On our campus we found that associate professors of color spent more time each week than white associates on mentoring students and service. While white women and women of color did equal amounts of university service (substantially more than men), women of color spent more time than white women on service to the profession and mentoring. Men of color spent more time on service to the university, service to the profession and mentoring than white men. While men spent more time than co-ethnic women on service to the profession (arguably, more prestigious and likely to be recognized), there are clear service imbalances by both race and gender, with associate women of color spending the most time on these activities, and associate white men the least.

What are some institutional approaches to helping midcareer faculty of color? In addition to the recommendations that we made for midcareer faculty more generally, we would note that universities need to institute clear guidelines that ensure that faculty of color are not held to higher standards than white faculty. Universities also need to promote diversity training as well as awareness among personnel committees and administrators of implicit bias, so that they consider how bias may affect external letters and student evaluations in promotions, as well as their own readings of the case. This may include training in soliciting and interpreting external letters.

Mutual mentoring programs aimed at faculty of color should also be supported, to help them recognize and address the biases they may face. Universities also need to develop strategies aimed at addressing the particular service burdens borne by faculty of color, including course releases for unusual committee service and recognition of increased time spent mentoring and on community service. In addition, universities need to consider the broader community and whether it is welcoming to diverse faculty, developing programs aimed at bettering faculty of color’s experiences. For example, universities should be engaged in discussions with campus and community police about implicit bias and racial profiling, and should send strong public messages in support of faculty and students of color when profiling occurs.

In addition to recruiting faculty of color, universities need to give more thought to retention as well, including those at midcareer. Investment in our faculty makes good sense. Diversity creates the conditions for greater creativity, and allows for much greater institutional change. Yet too many faculty of color are derailed in midcareer. We can make a difference, with recognition of the challenges and concentrated focus on solving the problems that limit the advancement of faculty of color.