You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

A new analysis from the American Academy of Arts & Sciences confirms a common fear: humanities majors and STEM majors dwell in separate academic silos. STEM majors, especially engineering students, take few humanities courses, the data show. And humanities majors take even fewer STEM courses. But the data also reveal that humanities courses are more popular than one might expect. College students, on the whole, earn more credits in the humanities than in STEM, even though science majors outnumber humanities majors.

Discussion of the New Study

Robert Townsend of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences and Carol Schneider of the Association of American Colleges and Universities will discuss the academy's new report on "This Week," Inside Higher Ed's free news podcast. Sign up for notification of new podcasts here.

Most studies of humanities enrollments look at how popular humanities majors are. The academy’s report takes a different approach. Instead of asking, “Who majors in the humanities?” the study asks, “Who takes humanities courses?”

The distinction is important. Many colleges that have eliminated small humanities departments have cited the low number of majors. This logic has angered many humanities professors, who have noted that STEM and business majors stand to benefit from their courses as much as humanities majors do.

The report, which the academy published today, draws on data collected by the National Center for Education Statistics. The center surveyed a nationally representative sample of students who received undergraduate degrees in 2008. The center’s data included college transcripts. By mining data from transcripts using the center’s PowerStats data analysis tool, the academy was able to determine how many course credits students earned in the humanities and how many in STEM.

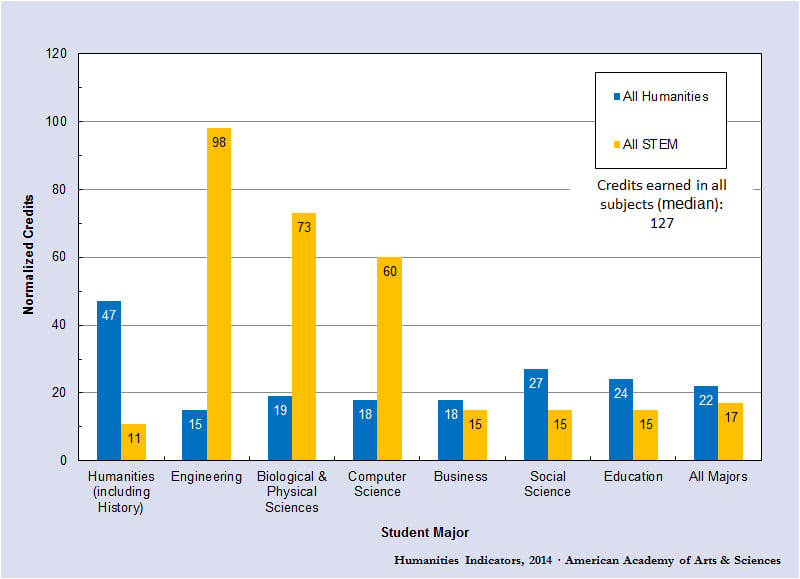

Median number of college credits earned by 2008 graduates in humanities and STEM, by student major.

The study is part of the academy’s Humanities Indicators project, which aims to collect and present humanities data.

Students who graduated in 2008 earned more credits in the humanities than in STEM, the study found. Humanities credits accounted for 17 percent of total credits earned by the typical graduate. In contrast, STEM credits accounted for 13 percent. (The researchers used median credit totals to calculate these percentages.)

Norman Bradburn, a professor emeritus and former provost at the University of Chicago and the co-principal investigator of the academy’s Humanities Indicators project, found the numbers for humanities course enrollment surprising. Humanities majors make up 12 percent of college graduates, whereas science majors make up 15 percent, he noted in his commentary on the study. Yet more people take humanities courses.

"The impression one gets is that nobody is taking humanities courses,” Bradburn said in an interview. “All the pressure is everyone should be taking STEM courses … Almost all the discussion about the humanities has been in terms of majoring in the humanities. I think majors are misleading. Pay attention to what courses people are taking more so than the major.”

James Brown, the executive director of the STEM Education Coalition, a Washington-based advocacy group that pushes policy makers to elevate STEM education as a national priority, said he didn’t see the humanities’ credit-total advantage as a problem.

“STEM courses and skills are an essential component of a well-rounded education, along with humanities, the arts and other subjects,” he said. “The bottom-line measure is whether college graduates are well-prepared to begin careers in the modern, increasingly technological economy which is demanding more STEM expertise across the board.”

The study counted foreign languages and literatures, linguistics, English, history, philosophy, religious studies, art, music, theater and writing (beyond composition) as humanities courses. The study classified computer science, engineering, biology, mathematics and statistics, physics, animal and agricultural sciences, military and science technologies and environmental sciences as STEM.

Why do the humanities claim a larger share of credits earned? General education requirements draw many non-majors to humanities courses. But another factor is the amount of crossover – or lack thereof – among disciplines. Humanities courses, more so than STEM courses, draw non-majors. But humanities majors venture into STEM far less often.

Engineering students earn the fewest humanities credits, the study found. Eleven percent of a typical engineering student’s credits come from humanities courses. Humanities majors, however, earn even fewer STEM credits. A typical humanities major will earn just 11 out of 127 credits in STEM. In other words, STEM fields make up about 8 percent of credits earned.

“What really caught our eye was the disparity … between the majors, and just how different they are in terms of their course-taking,” said Robert Townsend, the director of the academy’s Washington office.

Humanities majors earn 37 percent of their credits from humanities courses. Social sciences majors earn 22 percent of their credits from humanities courses.

Michael Roth, the president of Wesleyan University, has written at length on the liberal arts, most recently in his book Beyond the University: Why Liberal Education Matters. At Wesleyan, which has no course requirements (just course “expectations”), officials have found that “people in STEM fulfill the expectation to take courses across the curriculum more regularly than the humanities people do,” Roth said.

Many STEM courses require prerequisites – meaning humanities majors are often limited to broad introductory courses, he said.

STEM majors seeking to take humanities courses encounter obstacles of their own, however. Certain structural features of universities restrict humanities course-taking, Bradburn said. At many large universities, students apply directly to a college – often a college of engineering, education, business or some other field. “This structural feature works strongly against the development of humanities interests,” he said. “If you don’t have something that either forces you or strongly encourages you to take courses in different fields, you’re not going to discover fields you don’t know about.”

Bradburn said colleges ought to have “strong liberal education requirements for everybody.”

“I’m old-fashioned that way,” he said.

Roth, on the other hand, favored an open curriculum. Although Wesleyan has just “expectations,” he said he’d dissolve even those “expectations” if he could.

“You shouldn’t have to require people to expand their intellectual horizons,” he said. “You should be able to entice them to do so. Show them why it’s worth their while. When you have to require it, it demeans the enterprise.”

Rigorous academic advising, rather than general education requirements, could prompt students to explore new fields, the college president said.

Townsend, from the academy’s office, said that although the data covered 2008 graduates, humanities enrollment trends had not shifted much in the post-recession period, according to more recent data the academy is currently analyzing.

Conversations about humanities enrollments often set the humanities against STEM – a juxtaposition that the design of the academy’s study echoes. Yet there’s no reason why the humanities and STEM can’t get along, Roth said.

“When you talk about liberal education, that includes the sciences,” he said. “That includes all the STEM fields. Insofar as we can use reports like this to remind one another that education combines the sciences, social sciences, humanities and artistic practice, that will serve our students better.”