You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

When black students at the University of Missouri at Columbia issued a list of demands in October, eight items were listed. The demands were far-reaching, including the ouster of the university system president (a protest goal that was achieved), the hiring of more black faculty members and significant expansion of efforts to promote an inclusive campus. When students at Amherst College staged a sit-in in November, they had 11 demands.

But the demand lists being discussed this week at Hamilton College and Emory University are longer, more detailed -- and in some cases deal directly with decisions typically made by faculty members. And while some of the demands deal with long-festering issues in higher education, others are coming as a surprise to many on campuses, even those sympathetic to the idea that black students face far too much hostility and ignorance at their colleges.

Consider, for example, Hamilton College, where administrators this week received a list of demands from The Movement, an anonymous group of black students and supporters. By the group's count, there are 39 demands, but given that many of those demands have multiple parts, some critics say the demands have gotten so detailed that they are becoming difficult to discuss, and that the number tops 80.

One demand concerns a statement on the college's diversity webpage that was not known previously to be controversial. From the demands: "We, the students of Hamilton College, demand the immediate removal of the repugnant phrase listed within the college’s diversity page stating: 'A student at Hamilton can be grungy, geeky, athletic, gay, black, white, fashionable, artsy, nerdy, preppy, conservative … it doesn't really matter. At Hamilton you can be yourself -- and be respected for who you are.' This distasteful assertion trivializes the identities and experiences of marginalized groups and will not be tolerated further." (Italics are per the Movement's document.)

Like the lists of demands at many colleges, the one at Hamilton calls for the hiring of many more minority faculty members. But the list also suggests actions against those nonminority professors currently employed. One of the demands: "We, the students of Hamilton College, demand that white faculty are discouraged from leading departments about demographics and societies colonized, massacred and enslaved." It is unclear which fields would be covered.

Hamilton administrators may have had good reason not to expect criticism on historic figures honored on the campus. The college is named for Alexander Hamilton, who was an abolitionist. But the demands include that the college remove the name of Elihu Root from various campus structures. Root was a member of the Class of 1864; he served in positions such as secretary of state and U.S. senator and won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1912 for his work promoting the idea of arbitration rather than war to resolve conflicts between nations.

Because he held key positions at a time when the United States oversaw territories won in the Spanish-American War, the student demands say that Root's name has no place on campus "because of his historic role in colonization."

The college has not responded demand by demand, but has set up several campus discussions on issues of inclusiveness and diversity and has pledged to continue to encourage open discussions on these issues.

Emory on Wednesday did release a demand-by-demand response to 13 demands (many with subdemands), in many cases pledging to find ways to advance certain goals, but not necessarily agreeing to all of the numbers and timetables presented by students there.

Some of the demands deal with topics that Emory's response noted are supervised through the faculty governance process. (In these cases, Emory said it would encourage discussions, but didn't pledge to meet the demands in full.)

One such demand, for example, focused on student evaluations of faculty members. "We demand that the faculty evaluations that each student is required to complete for each of their professors include at least two open-ended questions such as: 'Has this professor made any microaggressions towards you on account of your race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, language and/or other identity?' and 'Do you think that this professor fits into the vision of Emory University being a community of care for individuals of all racial, gender, ability and class identities?' These questions on the faculty evaluations would help to ensure that there are repercussions or sanctions for racist actions performed by professors. We demand that these questions be added to the faculty evaluations by the end of this semester, fall 2015."

The demands that are coming out this week are being widely mocked in the conservative blogosphere.

Others, while opposing many of the specific demands, are offering some sympathy for the students. "Students have the right to raise whatever concerns or demands they wish," said Hank Reichman, chair of the American Association of University Professors Committee A on Academic Freedom, Tenure and Governance, via email. "Faculty and administrators should respond to these demands in a spirit of respectful engagement and with the goal of furthering the students' education. It would be foolish to demand of college-age students the sort of sophisticated understanding of academic freedom we would desire of faculty members and administrators."

At the same time, he said, the kinds of demands being made with regard to faculty members were in many cases ill-advised.

The demand at Hamilton to discourage white faculty members from chairing certain departments "would impose a prejudicial and possibly illegal racial restriction on the hiring of faculty," he said.

And the demand at Emory about faculty evaluations would require questions that are "far too subjective" and are "prejudicial," Reichman said. He added that "a better approach would be to permit students to file complaints about specific mistreatment, backed by evidence, and to handle those through mechanisms that guarantee any faculty member so charged with fair due process protections."

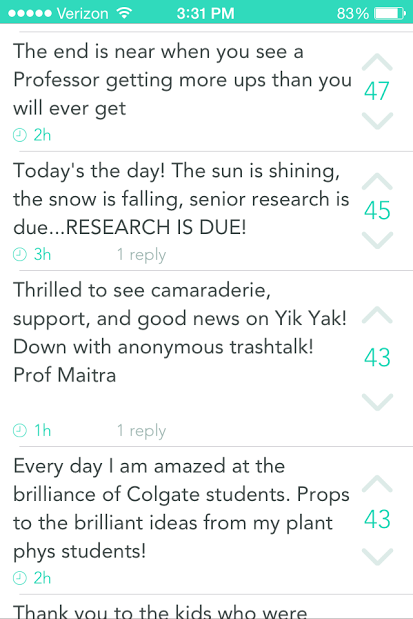

Can Yik Yak Be Banned?

At both Hamilton and Emory (and many other campuses), there are demands about banning Yik Yak, the social media app that has become a place for many people to make racist and sexist comments, anonymously, about specific individuals. Many violent threats have also been made on Yik Yak -- and many administrators would love to see the service go away. However, most academic leaders have determined that it would be impossible to simply ban it.

At both Hamilton and Emory (and many other campuses), there are demands about banning Yik Yak, the social media app that has become a place for many people to make racist and sexist comments, anonymously, about specific individuals. Many violent threats have also been made on Yik Yak -- and many administrators would love to see the service go away. However, most academic leaders have determined that it would be impossible to simply ban it.

The Hamilton students demand that Yik Yak be banned from the area, while the Emory students called for the university to use "geofencing" to block Yik Yak on campus. Emory said it would study the feasibility of the idea.

Hilary McQuaide, director of communications for Yik Yak, said colleges would fail in geofencing efforts. The concept is to block access -- and Yik Yak works with high schools to do this because the company doesn't want users under the age of 18. But McQuaide said that while colleges could block people from using institutions' wireless systems, they would be powerless when students used mobile phones with their own connections (which is of course the norm for students).

Tracy Mitrano, a consultant on technology and legal issues in higher education (and an Inside Higher Ed blogger), said she too doubts most colleges would truly be able to block Yik Yak beyond their own networks.

Mitrano said there may well be more important questions and better ways to consider the issue of Yik Yak's impact. Via email, she said that colleges should be talking about such issues as "how race is experienced and discussed on campus, what does free speech mean (and whether or not it matters on either a private or public campus), what does institutional policy on conduct mean, what choices might student make about their use of social media -- especially that which is anonymous -- to express their ideas, and how much ideas matter in the larger process of education. For me observing this entire set of events, taking the opportunity to use these challenging issues as fodder for the educational process appears to be an opportunity lost by reducing the complexity of it down to simple questions of 'to block or not to block' or to a zero-sum game of race versus speech."