You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

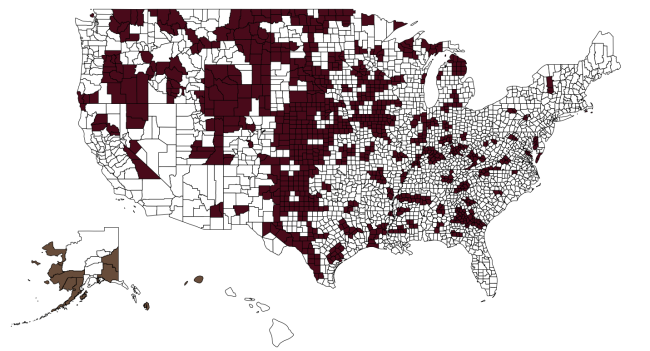

Education deserts in commuting zones

American Council on Education

If only tuition were lower, and high school students were armed with better data. That’s the idea that has guided the policy discussion about college access and affordability: to make better enrollment decisions, the story goes, students need money and information.

But that narrative misses an important point about how students make decisions: for many students, where they go to college depends largely on where they live, according to a study commissioned by the American Council on Education.

The majority of incoming freshmen attending public four-year colleges and universities enroll within 50 miles of their home, the study found. And the farther students live from any particular college, the less likely they are to enroll.

“The zip code that a child is born into oftentimes determines their life chances,” said Nick Hillman, an author of the study and assistant professor of education leadership and policy analysis at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. “Place matters because it reinforces existing inequalities.”

At public four-year colleges, the median distance students live from home is 18 miles. That number is 46 miles for private nonprofit four-year colleges, and only eight miles at public two-year colleges.

.png)

But when it comes to college choice, Hillman thinks geography is overlooked. Policy makers focus too much on expanding students’ awareness of their possible choices, he said, without realizing that students’ options are already limited.

The study points to tools like the College Scorecard, which are intended to help students make informed, thoughtful decisions about where to enroll. But if a student needs to stay close to her family, what will she gain by learning that the perfect institution is hundreds of miles away?

“The conversation pretty much ends with, ‘Hey, get better information in the hands of students,’” Hillman said. “But the way that prospective students use information is very different depending on what kinds of students you're looking at.”

The crux of the problem is a misalignment of expectations: from policy makers’ perspective, students would attend college at whatever institution is best for them. But for some students, location is nonnegotiable -- and often, that means their options are dramatically limited.

For upper-class students, having more information might help; they have the flexibility to travel, and they can afford to shop around. But it isn’t enough for working-class students, who may need to choose from the options available nearby.

“Most of the conversations today overlooks the working-class student and prioritizes the upper-class student,” Hillman said. “It’s just really frustrating from the academic side -- and even more frustrating from a policy angle.”

Education Deserts

And for working-class students who want to stay close to home, what happens when there aren’t any colleges nearby? No matter how well-informed these students are, they don’t end up with many options.

These are students who live in what the study calls “education deserts.” An area qualifies as an education desert if there aren’t any colleges at all, or if one community college is the only broad-access public institution nearby.

An education desert can include private and public colleges that are particularly selective. That’s because local residents may not be accepted into those colleges -- which means they have even fewer options. And if there’s only one community college within commuting distance, that’s likely where those residents will end up.

“The role of community colleges is paramount,” said Lorelle Espinosa, assistant vice president at ACE’s Center for Policy Research and Strategy. “We need to be thinking about the institutions that exist in these places and making sure they are equipped to serve students.”

Policy makers need to focus on solutions that will help all students, she added, not just those with the freedom to travel.

Most of the country’s education deserts are in the Midwest and Great Plains states, the study found. Community colleges enroll over half of students who live in education deserts, while private institutions account for less than 15 percent of education desert enrollments.

“Every state should have a good inventory of their deserts,” Hillman said. “They should know exactly what colleges are operating in these areas, to what extent they’re serving their communities.”

And after that, Hillman thinks policy makers should look at how they fund their colleges in education deserts, perhaps switching from performance-based models to equity-based models. In areas where opportunity is slim, he said, policy makers need to focus on building up the colleges that serve their communities.

Hillman’s family lives in northern Indiana, where only a few broad-access public colleges serve large numbers of students. But not all policy makers have lived in an area where opportunities are so slim. And that, Hillman said, is why they overlook geography: many of them traveled far from home to attend college, and many of their children have done the same.

“Policy makers are not in tune with the reality of how working-class families make decisions,” he said.