You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

SAN FRANCISCO -- Midcareer, tenured faculty members power their institutions, but many also suffer from something like middle-child syndrome. Past the defined demands of achieving tenure but often still relative newbies, they can get lost in the institutional fray. Preliminary research to be presented here today at the annual meeting of the Association of American Colleges and Universities gives new insight into these professors’ thoughts and experiences and proposes a framework for thinking about them -- one that cuts through stereotypes that they’re unmotivated.

“It seemed pretty ironic that there were very highly privileged workers with a lot of autonomy who didn’t feel lit up by and aligned with their work,” said co-investigator Karla Erickson, associate dean and chair of sociology at Grinnell College, of accounts of tenured professors not having the same drive as their more junior colleagues. “And our findings go against the notion of deadwood workers who, after they receive tenure, simply ‘show up.’”

For her study, to be discussed in a session called “Rethinking the Midcareer Malaise: New Lessons From Posttenure Liberal Arts Faculty,” Erickson partnered with Jan E. Thomas, senior associate provost and professor of sociology and women’s studies at Kenyon College, and Tamara Beauboeuf, professor of women’s, gender and sexuality studies at DePauw University. Beyond wanting to challenge prevailing ideas about posttenure professors, they had a bit of personal motivation: all are midcareer professors themselves.

Hoping to elicit meaningful responses from their subjects -- all posttenure, pre-retirement-minded professors on their three campuses -- Erickson, Thomas and Beauboeuf avoided detailed questions about workload and focused rather on mind-set. They used developmental model language for a survey that led to subsequent in-person interviews.

Men and women responded in roughly equal numbers -- surprising for a voluntary survey, in which women respondents would typically be overrepresented. Respondents totaled 239, along with 56 interviewees.

Survey questions included, "Is being or becoming a full professor important to you? Why or why not?," and "In an ideal week, how would you spend your working hours?" (Note: Full professors who were not yet thinking about retirement were over half of respondents.)

A major finding -- again, perhaps surprising -- was that most professors enjoy teaching and want to do more of it. Over all, the researchers describe the posttenure period as an active phase of navigating “meaningful versus futile service, identifying new pathways in teaching and research, and finding synergies between organizational needs and one’s own creative and intellectual contributions.” They also define a basic tension between the need for faculty “to remain engaged while navigating what we conceptualize as ‘institutional trenches.’”

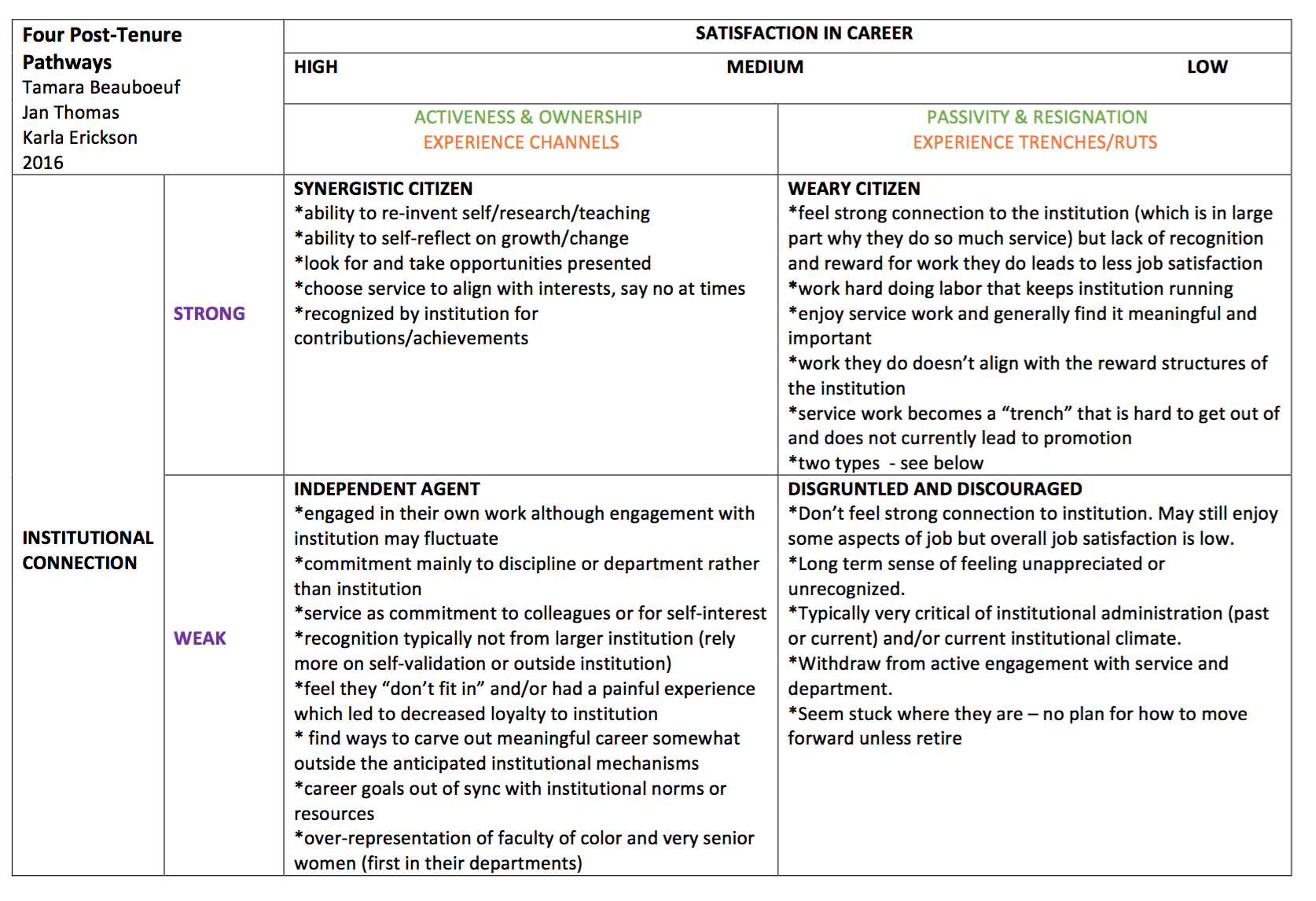

Elaborating on that tension, Erickson, Thompson and Beauboeuf designed a typology describing professors as either synergistic citizens, independent agents, weary citizens, or disgruntled and discouraged.

Synergistic citizens expressed high levels of job satisfaction because they were working hard and felt that their contributions were valued by their campuses. One professor for example, said he was able to transform his writing after tenure because his institution had afforded him the "freedom to fail."

Independent agents, meanwhile, worked hard, but did so largely on their own because they didn’t perceive their contributions were valued by their institutions. Sometimes a specific incident or break of trust prompted such feelings. Senior department women and faculty members of color were overrepresented in this group.

Weary citizens -- who were in many ways similar to synergistic citizens -- described themselves as eager to contribute to their institutions. But their service often lacked meaning, seemed undervalued or otherwise led to a sense of marginalization.

Disgruntled and discouraged professors liked aspects of their work but lacked a sense of connection to or recognition by their institutions. Morale was low.

Faculty ‘Pathways,’ Not Fixed Types

Beauboeuf said it helps to think less about types than “pathways” for posttenure faculty members to follow, pathways which reflect the "degree to which faculty needs and growth are taken up by the opportunities and rewards of their institutions."

Ideally, she said, "there would be a synergy between both -- and we do have evidence of this -- but our research also attunes us to the ways faculty who engage in labor that is critical but invisible in the reward structure, or who have been hurt through disparagement of their contributions and competence, are placed on pathways of reduced career satisfaction and weakened connection to the institution.”

Sometimes there was a lack of fit between the professor and the institution. But some common themes emerged among dissatisfied professors. Some reported that their institutions did not have clear promotion standards, for example; Erickson recommended that institutions wanting to better support posttenure professors shore up their promotion guidelines and expectations.

“We saw faculty who were floundering at one school who probably would have been ignited at another school, because there wasn’t a nice level of synergy between what they wanted to do and what their [institutions] want them to do,” she said.

Beyond adopting clear standards for promotion, Erickson also recommended that institutions offer formal opportunities for professors to reflect on their career trajectories -- specifically in terms of service -- and their other opportunities for “reinvention and rejuvenation.”

“This would help professors feel as if this long swath of their career is punctuated” with meaningful, identified phases, Erickson said. “Or you might say, ‘Hey, why is this person on eight committees?” which might signal that service is plentiful but not meaningful.

Some subjects, for example, reported extreme pride from service on just one committee, which they felt made a real difference on their campus.

Such check-ins can help professors avoid gendered or other kinds of service “traps,” Erickson said, referring to the fact that women are more likely to perform what’s known as “invisible” labor, such as disproportionate service or advising duties, on their campuses.

The researchers chose to focus on typologies at this stage in their research over hard survey response data, in part to help institutions frame or reframe how they think about supporting midcareer professors. They plan to refer to their survey data for future publications and presentations.

Thomas said the roughly equal representation of men and women respondents from all three institutions “led us to believe we had tapped into issues that were important across our campuses,” and the “personal and thoughtful responses we got to the open-ended questions on the survey also led us to believe that faculty wanted to talk about these issues and reflect on their careers. We wanted to take advantage of that momentum.”

They also note two methodological weaknesses: those who opted in to the survey and interviews could be more engaged in their careers than nonrespondents. In other words, there may well be “deadwood” midcareer professors who simply aren't represented in the study. Erickson admitted that’s a possibility but said the near-equal representation of men and women in the sample indicates that the survey was of broad interest to professors.

“We had a lot of people thanking us for not making another survey about how much work they do,” she said.

The study also only considered professors at teaching-oriented liberal arts colleges, who may well be more likely to report liking teaching than, say, a professor at a research institution. Erickson suggested further study is needed across a variety of institution types.

“There may well be a type that we did not see,” she said.

At the very least, the study offers an alternative to the posttenure malaise narrative. Asked why that narrative remains so strong in the minds of some, Erickson said it’s a “powerful story” due to the nature of tenure itself. “There’s a kind of professional envy -- we have a level of security that almost nobody has.”

Additionally, she said, “individual actors” perpetuate it through less-than-optimal professional behavior. Reasons for that are complicated, including that many professors reach a kind of professional peak when they achieve tenure, despite the fact that they haven’t peaked intellectually.

“There’s a sense of lack of visibility, like nobody cares about their projects anymore,” Erickson said, only half kidding. She noted that posttenure faculty members are so eager for professional guidance and meaningful development that she encounters unusual gratitude from those middle-years professors she helps through her job.

“Supporting midcareer professors -- that’s when I get the notes and art and chocolate,” she laughed.

Erickson added, “What’s really important here is to see how organizational culture affected people.”

Listening to Posttenure Professors, Recognizing Their Work

Thomas said the findings matter because “we know very little about the arc of the faculty career and how faculty continue to grow and develop over the 20, 30 or 40 years that come after tenure.” The need for guidelines and general guidance doesn’t stop after tenure, she said, and may well increase, given the length of the midcareer phase. The few years after tenure can be especially critical for helping faculty members reflect on the next stage of their careers, identify new goals and create an “intentional pathway” for getting there.

Kerry Ann Rockquemore, an author and speaker on faculty development who founded the National Center for Faculty Development and Diversity, and an Inside Higher Ed columnist, said via email that the new typology is “incredibly useful because it helps us to understand the range and complexity of faculty members’ experiences at midcareer.”

Rockquemore’s own experiences working with midcareer faculty members also counter the deadwood theory, she said. In reality, she said, “there is a pervasive belief that once faculty members win tenure, they no longer need mentoring. And because many assume there's no need for posttenure mentoring, there are few intentional spaces, structures or programs for newly tenured faculty members to pause, breathe and ask themselves important questions like: What's next? What posttenure pathway will I choose? What kind of skills, strategies, mentors, and networks do I need to make a successful transition from assistant to associate professor? How can I contribute to my campus community in ways that are both collectively useful and draw on my skills and talents?”

She added, “These are all perfectly normal questions for someone to ask after going through the tenure-track experience, and the sooner they get resolved, the better it is for the individual and their institution.” Rockquemore’s own organization recently piloted its own posttenure pathfinders program based on volume of requests it receives for this kind of help.

“Our members are consistently requesting midcareer support services.”

What can be done? Rockquemore agreed that clarifying posttenure pathways is “an excellent idea,” as are posttenure mentoring programs, leadership development programs and opportunities for reflective conversation about meaningful work and equitable contribution.

Jeffrey Alstete, a professor of management and business administration at Iona College who has studied midcareer faculty development, also found the typologies “sensible and accurate,” but said he suspected them to vary by institution type and discipline.

“I not only believe that most midcareer professors are not deadwood, I would add that most late-career tenured professors are also actively engaged in their teaching, research and service endeavors,” he said, adding that he knew many mid- and even later-career professors who could be classified according to the framework -- especially as synergistic citizens.

Alstete said he also knew highly motivated independent agents who “find their own rewards from the process of their hard work in itself, as well as successful outcomes in seeing their students learn, finding that their research is recognized and that their service contributions are having an impact.”

Over all, posttenure faculty members face a set of complex challenges, from increased internal and external scrutiny to changing organizational cultures to rapidly changing technology, not to mention a complex workload, he said. Posttenure faculty development programs can help -- “if they seek out participation and input from a variety of faculty members, including tenured professors, and consult them in the planning process.”

Beauboeuf reiterated that pathways aren’t necessarily fixed types. But institutional support “needs to be ongoing and extend well beyond tenure and promotion,” she said. “We believe that administrators need to remember that the majority of a faculty [member]'s career occurs posttenure, and that faculty are lifelong learners. Posttenure can be a dynamic period of reinvention, particularly if institutions are willing to listen to faculty and recognize the work they do.”