You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock

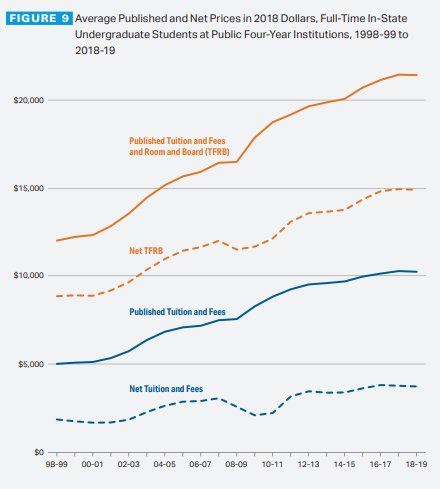

Average published tuition and fees at public two- and four-year colleges dropped by the smallest of margins between 2017-18 and 2018-19, the College Board reported Tuesday, with costs at private nonprofit four-year colleges rising slightly.

Meanwhile, the typical undergraduate last year received just marginally higher levels of aid.

Adjusting for inflation, the average price for a year at a public two-year college dropped $10, or 0.3 percent, from $3,670 to $3,660, according to new findings from the College Board, which reports annually on both college pricing and student aid. The figure represents the first drop in two-year college pricing since 2008-09, near the beginning of the Great Recession.

Four-year public institutions saw a similar small price drop, from $10,270 to $10,230, or 0.4 percent, the first downturn since the College Board began publishing tuition and fee data in 1990.

Private four-year colleges’ average tuition and fees rose 0.3 percent, from $35,720 to $35,830.

Over all, tuition and fees have moderated since the recession, said Sandy Baum, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute and a co-author of the report. “But over the long run, prices are still going up a lot,” she said. “And you can’t look at those prices without looking at what’s happened to student aid.” For the most part, she said, it has not kept pace with larger trends in the price of college.

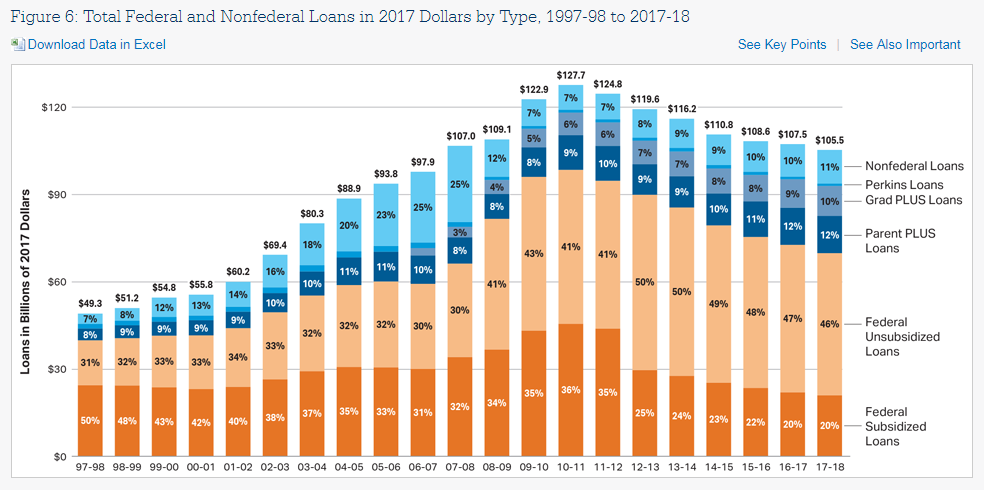

In a companion report, the College Board said total aid for the typical undergraduate rose just slightly between the 2016-17 and 2017-18 academic years, from $14,620 to $14,790, or 1.2 percent; meanwhile, the average federal loan dropped 3.6 percent, from $4,680 to $4,510.

The new student aid figures lag one year behind the new tuition and fees figures.

Baum said that even with steadily rising prices, the new statistics belie the popular idea that college costs are out of control. “People still think that prices are rising really rapidly -- and they’re not.”

Student debt is shrinking as well, she said. Last year, the total amount of student loans dropped for the seventh consecutive year. Over all, the figure has shrunk from a high of $127.7 billion in 2010-11 to $105.5 billion in 2017-18, a drop of 17.4 percent -- to lower than pre-recession levels. Total student aid, including nonfederal loans, while higher than the previous year, has dropped 7.8 percent since its high in 2010-11, accounting for inflation. The decline in the for-profit sector "probably contributes to the decline in borrowing, since for-profit students borrow more on average than others," Baum said.

But like most indicators, she said, both prices and student debt are cyclical and could well shift again. While state funding is rising in many cases, she said, lawmakers need to more closely consider the relationship between funding and student need. States like Georgia and South Carolina, she said, are investing heavily in student aid, but it’s not necessarily going to students with the greatest need.

Over all, she said, more than half of the aid dollars that public four-year institutions distribute are not based on need.

At private institutions, a different narrative is emerging, Baum said. Just as aid at elite private nonprofit institutions has evolved to become “very progressive,” with generous grants to low-income students, other private institutions “just don’t have the money to make it that cheap for low-income students. They are pretty much discounting the same amount at all income levels,” using aid to entice a broad swath of students to attend.

“It’s not very progressive,” she said.