You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

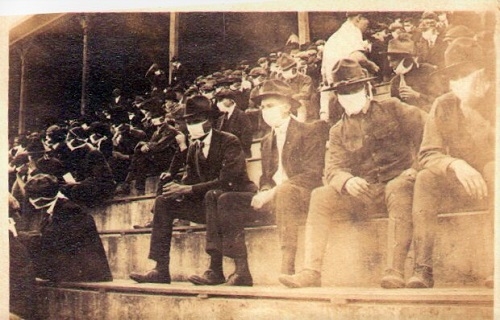

Masked fans watch a Georgia Institute of Technology football game in 1918, during the flu pandemic. The photo was taken by a 1918 alumnus and has been shared widely by his great-grandson, a 2001 Georgia Tech graduate.

Thomas Carter and Andy McNeil

The message out of Texas A&M University is clear and confident: there will be Aggie football this fall. Whether or not the university is able to fill its 102,733-seat stadium to capacity, A&M wants to be a national and state symbol of the return to normalcy after the coronavirus pandemic shut down the College Station campus along with much of the country.

A&M athletic director Ross Bjork remembers how football fans coordinated wearing the colors of the American flag for the Aggies' first home game after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. Fans sitting in each of the three levels of Kyle Field all wore the same color. The “Red, White and Blue Out” was a display of patriotism that “no act of togetherness and camaraderie on such a grand and public scale could match,” said 12th Man Magazine, the university athletic foundation’s publication. Bjork envisions a similar, triumphant return for football following the worst of the pandemic.

“That’s the power of sports. It provides hope,” Bjork said. “It provides this confidence level and something for people in our community to rally around.”

The importance of college football to the state partly fueled the decision by A&M to safely bring athletes back to competition this year, Bjork said. A few other colleges that have announced plans to reopen their campuses this fall have also stated their intention to allow their football programs to resume. Despite the risk of infection that health experts say competition poses to athletes, the colleges are expressing hope and positivity -- with a sprinkle of doubt in case they need to change or adjust plans -- in their public statements in an effort to reassure students and parents, alumni and boosters, and local communities that sports will be back soon.

The assurances mask widespread uncertainty about how such a fall season would be structured, especially when it comes to the fan experience.

Bjork said his priority is a "full" experience and safe environment for athletes and fans, but "What that looks like and how we get there has yet to be determined."

Athletic directors, conference leaders and university presidents are discussing a range of scenarios -- a full season on schedule, a delayed start, games limited to specific regions, a reduced season or a season interrupted by more COVID-19 outbreaks.

"Everything is possible," said Lawrence Schovanec, president of Texas Tech University and vice chair of the Board of Directors for the Big 12 conference. "We have to recognize that it would be folly to make emphatic statements that something will or will not happen. We have to be open that there are changing conditions. Even though we are moving forward with athletic events, we have to recognize that there are changes that are out of our control."

There’s pressure on these institutions to not only bring athletes back, but to put paying fans back in the stands and resume the important game-day rituals that bring in millions in yearly ticket sales and donation revenue for athletic departments, said Welch Suggs, associate director of the Grady Sports Media Initiative at the University of Georgia. Suggs noted the strong ties that exist in the South between college football and civic and business leaders in these states, including at Georgia, which, like A&M, is a member of the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s Division I Southeastern Conference.

“College football is where it’s at in the South,” Suggs said. “No other sport has the footprint that football does, in terms of the size and scope or where it fits in our psychology.”

Some commenters on social media point to the low death rate due to COVID-19 reported among college-age individuals as a reason to have the fall season, but Suggs finds this logic unacceptable. Colleges are going to do their best to make the return to campus and sports as safe as possible, but the idea of students getting COVID-19 or dying of the illness is “what’s keeping everybody up at night,” he said.

“The horrible thing about this is we have no way of predicting whether those precautions are going to be safe enough,” Suggs said. “We care about that in terms of classrooms, just as much as we care about that for competition.”

Chris Hostler, a physician epidemiologist and assistant professor of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine, said there is a “very good understanding” among athletics officials he works with that there are going to be outbreaks of COVID-19 infection, no matter how many precautions staff and athletes take to reduce the risk of spreading the disease. Hostler is a partner with Infection Control Education for Major Sports, or ICS, a company separate from Duke that is contracted by the National Football League and Big 12 conference to provide infection control consulting to sports entities.

“There’s no ‘no-risk scenario’ here, whether you have college sports or no college sports,” Hostler said. “There are going to be college athletes that contract this illness.”

Hostler said college leaders are aware of the potential downsides of letting students play.

"They're all pretty understanding and pretty accepting that that’s kind of the world that we live in right now," he said.

The nature of collegiate sports -- direct contact with others on the field, in training facilities and locker rooms, lack of control over athlete behavior -- make the risk of infection for college athletes higher than for other college students or professional athletes, Hostler said. The goal of ICS is to get infection-prevention standards in athletic facilities to a similar level as that of hospitals. This may mean frequently testing athletes and department staff and requiring more social distancing during practices and training and conditioning, he said.

Hostler was hesitant to say what universities’ risk mitigation plans will look like. Different measures will be taken depending on the testing capacity of the counties and states in which the colleges are located and local predictions about infection rates, all of which could change over the course of the summer, he said.

Schovanec said despite social distancing in football being "contrary to the game itself" and the cost of frequent COVID-19 testing, Texas Tech will move ahead with the fall season in the safest way possible. The university's athletics department determined it would cost about $17,000 to test athletes and staff just one time.

"We want to play, but we’re not going to compromise anybody’s health," Schovanec said. "No, we cannot be absolute in our guarantees. We can do our best with the advice of our health experts."

Some college and government officials have said the risk of commencing college athletics in the fall is too high. The California Collegiate Athletic Association, or CCAA, which includes 13 Division II athletics programs from across the state, announced on May 12 it would suspend fall athletics. The announcement came after the California State University system announced its plan for a virtual semester. A statement from the CCAA said competition will resume when it is “safe and appropriate to do so for all of its members.”

Kate Brown, the governor of Oregon, said last week that large gatherings such as sporting events cannot return to the state until at least September, and likely not until there are adequate treatments or a vaccine for COVID-19, ESPN reported.

Suggs said various NCAA and state leaders are considering the fall season “from all different angles,” while the association itself has not set any specific dates for the start of the fall preseason, which he believes is out of character for an organization that normally sets strict competition standards in its bylaws. In a video posted to Twitter on May 8 about the NCAA’s response to the pandemic, President Mark Emmert said the return to sports will have to be a local decision. Brian Hainline, the NCAA’s chief medical officer, said there will be no national start time for college sports.

“This is so differentiated by geographies and urban density and a whole array of different demographic variables, that the level of confidence is going to vary from campus to campus,” Emmert said in the video. “Those have got to be local decisions, based on the best available evidence and data that they have in front of them.”

Bjork, of A&M, said the various NCAA conferences, which are largely region-based, should have the most authority and ability to make decisions on preseason start dates and scheduling. The SEC has prohibited any voluntary or mandatory in-person activities until May 31, but Texas is allowing commercial gyms to reopen on May 18. A&M is anticipating its athletes will work out on their own and is sending out safety tips on reducing risk of contracting the virus, Bjork said. He and other university medical experts would much rather see their own facilities open to offer athletes a controlled training environment, but the conference mandate won’t allow it at this time.

Gene Taylor, athletic director for Kansas State University, which is in the Big 12, said the different reopening phases between states are where preseason planning gets “a little bit challenging.” That conference also has a prohibition on in-person activities until May 31, but like Texas, Kansas plans to reopen gyms today. Despite some differences between states -- the Big 12 encompasses five of them -- Taylor said so far, the conference has been approaching the fall season in “lockstep” and hopes that uniformity will continue.

“We’re all wanting to do collectively what’s best for the Big 12,” Taylor said. “We’ve been talking about staying solid as a conference.”

The longer conferences wait to allow the start of conditioning, the less time athletes will have to prepare for a football season that starts in late August or early September, which means an increased risk of injuries, Hainline said in the NCAA video. He said there needs to be agreement on a minimum length of the preseason to ensure athletes are well prepared. Taylor said discussions among Big 12 athletic directors and football trainers have landed on an agreement of six weeks of preparation, likely starting in mid-July, which is where officials feel most confident. But they have also considered as little as a four-week training period, which Taylor said is “rushing these kids back without really thinking.”

“Four weeks is where it gets uncomfortable,” Taylor said. “I think our strength coaches and trainers would say from a safety perspective, that’s not what we want to do.”

Athletic directors can talk “until we’re blue in the face” about plans to bring athletes back to campus, but decisions will ultimately fall to university presidents and chancellors, Taylor said. University announcements from most in the Big 12 conference, such as Kansas State, the University of Texas at Austin and Baylor University, have said that they “intend,” “plan” or have the “goal of” commencing in-person classes in the fall, without explicitly mentioning plans for athletics. Schovanec said his message to the university did mention athletics because of its role in campus life and the importance of football to the overall health of Texas Tech's athletics department.

"I would hate to convey an attitude that we’re driven to this by monetary concerns," he said. "We’re not going to compromise health, but at the same time, we have to be realistic. In order for other athletics to engage, we have to have football."

A&M will move forward until updated health information or officials say otherwise, which Bjork acknowledged will displease people who fear the further spread of COVID-19. There’s some doubt in his mind because athletics has not been given the all clear by authorities, but the clock is ticking, he said.

“We haven’t been told we can’t play,” he said. “You can’t be paralyzed by fear. You have to move forward in a positive and safe manner, and that’s how we’re approaching it.”