You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Klaus Vedfelt/Getty Images

Four-year colleges and universities cut tenure-track hiring by 25 percent around the time of the Great Recession -- and hires of people of color declined disproportionately, especially at public and research-oriented institutions, according to a new study in Sociological Science.

In addition to these data, the new paper offers another, urgent takeaway: the same reversal of progress toward faculty diversity could happen in the COVID-19 era, if institutions don’t take steps to ensure it doesn’t.

“That hires of faculty of color declined during the Great Recession may have gone unnoticed by administrators struggling to keep the ship afloat,” the study says. “Provosts and deans facing the COVID-19 crisis should take note that institutions facing uncertainty may reduce new-hire diversity unwittingly. It may be that public and research-oriented institutions will again face the greatest uncertainty over the next few years and will again see the greatest declines in the diversity of new faculty.”

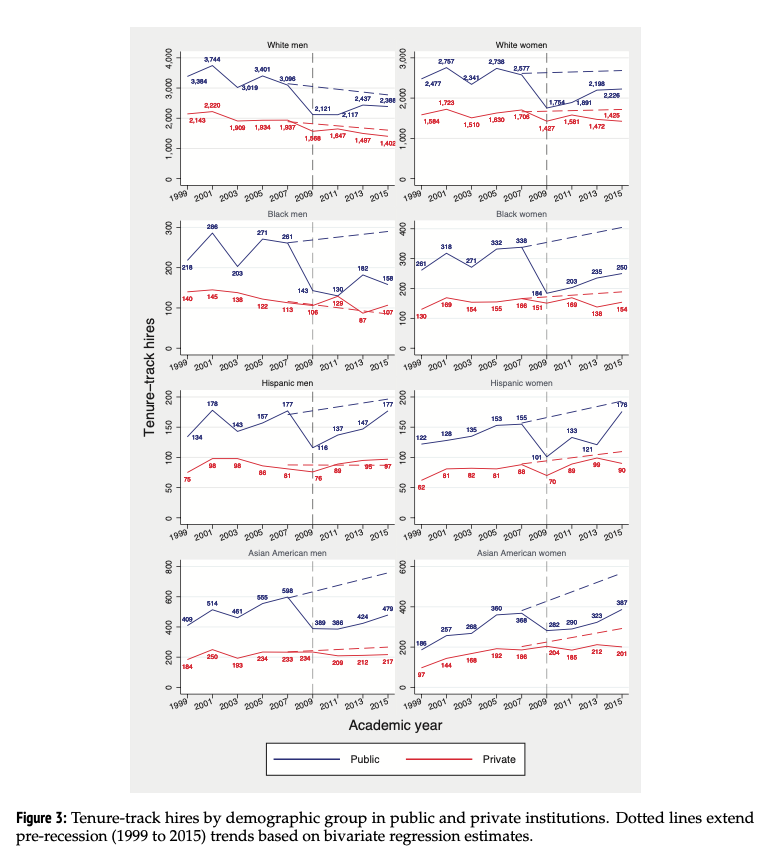

For their study, the researchers analyzed federal data on tenure-track hiring from 1999 to 2015, roughly dividing that period into pre-recession (1999 to 2007), recession (2007 to 2011) and post-recession (2011 to 2015). Over all, they found that pre-recession tenure-track hires averaged 13,535 per year. Between 2007 and 2009, in particular, total hires declined 25 percent. Public institution hires dropped by 31 percent, and private institution hires dropped by 14 percent during that time. Both public and private institutions experienced a slow recovery, and neither rebounded fully: at publics, hiring was still down from 2007 by 11 percent by 2015; at private institutions, hiring was still down by 15 percent by 2015.

Next, the researchers looked at hiring trends for six major demographic groups: Black, Hispanic and Asian American men and women. They found that prior to the recession, public institution hires in all six groups had been rising. Comparatively, hires of white women had been almost flat, and hires of white men had been declining.

After 2007, however, hiring “changed course sharply for people of color,” the study found, especially for Black men and women. That is, if pre-recession trends had continued between 2007 and 2009, public institutions would have seen hires of Black men and women rise by 3 percent and 5 percent, respectively, and hires of Hispanic men and women rise by 4 percent and 6 percent.

After 2007, however, hiring “changed course sharply for people of color,” the study found, especially for Black men and women. That is, if pre-recession trends had continued between 2007 and 2009, public institutions would have seen hires of Black men and women rise by 3 percent and 5 percent, respectively, and hires of Hispanic men and women rise by 4 percent and 6 percent.

Instead, hiring of Black men and women declined by 45 percent, and hiring of Hispanic men and women declined by 35 percent.

For Asian American women and men, if pre-recession trends had continued, hires would have risen by 12 percent and 7 percent, respectively. Here, too, they declined -- by 23 percent and 35 percent, respectively.

Among white women, had pre-recession trends continued, hires would have risen by 1 percent, and hires of white men would have declined by 3 percent. Instead, they both declined by about 31 percent.

Uncertainty Breeds Bias

Recession-related declines were shallower at private institutions. Before the recession, hires of Black, Hispanic and Asian American women and Asian American men were growing, whereas hires of Black and Hispanic men were declining, according to the study.

Between 2007 and 2009, numbers of Black and Hispanic men hired continued to decline, and Black and Hispanic women began to decline.

The positive trend for Asian American men flattened during the recession at private institutions, meanwhile, and the trend for Asian American women continued upward.

This is what the authors expected to happen, as public institutions experienced large financial cuts and greater uncertainty during the recession, and sociological theory suggests that uncertainty exacerbates in-group favoritism. Prior research also finds that employers are more likely to lay off women and people of color and are less likely to hire them during periods of financial uncertainty.

While these raw data are illuminating, the researchers wanted to compare how different demographic groups fared during the recession, relative to each other.

Pre-recession, at both private and public institutions, Black and Hispanic men and women were “holding their own” as a proportion of new faculty, meaning the point estimate for annual change in group share was at zero, or slightly positive. The share of Asian American men and women was above zero, meaning their share was increasing.

During the recession, however, all six groups -- Black, Hispanic and Asian American men and women -- lost ground, compared to the pre-recession period. Private institutions saw very small changes in the share of jobs going to Black and Hispanic men and women, and the pre-recession growth in in hiring for Asian American men and women was eliminated. Hiring pattern shifts were much more dramatic in public institutions, according to the study.

Translating annual change odds into actual percentage shifts, Black men and women’s share of hires -- which, again, had been stable prior to the recession -- declined at 2.5 percent annually during the recession and increased at 0.8 percent and 1.9 percent, respectively, after the recession. The pattern for Hispanic men and women was similar, with men’s shares declining at about 1 percent annually during the recession and about 1.5 percent afterward. Asian American men and women, whose share of new hires had been increasing prior to the recession by 1.8 percent and 3 percent annually, respectively, saw the greatest recession-era declines, of 3.9 percent and 1.9 percent, respectively. Following the recession, their share of hires began to rise again, at about 2.5 percent annually for both men and women.

At private institutions, comparatively, there was virtually no change for Black men and Hispanic women. Hispanic men saw an annual increase of 0.4 percent during the recession and 0.5 percent after the recession. Small annual increases stopped for Black women and Asian American men. The biggest change was for Asian American women, who saw their annual 1.6 percent growth rate prior to the recession eliminated during the recession.

White faculty hires fared well, meanwhile. Shares of white women hired at public institutions had been declining by 1 percent annually prior to the recession, and the recession stopped that decline, turning it into a very small increase thereafter. At private institutions, the share of white women hired grew at about 0.3 percent annually both before and during the recession, and then dropped to zero, or stayed steady. White men, who had seen their share of new hires decline significantly prior to the recession, saw those declines “attenuated” during the economic crisis, at both public and private colleges and universities, the study says. After the recession, the share of white men hired as new tenure-track professors started to decline again, but less significantly than before.

Beyond a public-private divide, the researchers compared how institutions responded to the recession in terms of hiring by research activity level. They found that the recession brought the sharpest trend changes in highest-research-activity institutions, and that hires among people color recovered most quickly at highest-research-activity institutions, by Carnegie classification.

“This pattern is consistent with our prediction that the recession induced the greatest financial uncertainty in research-oriented universities and that uncertainty is at the root of the decline in the hiring of women and people of color,” the study says. “Uncertainty may have led faculties to rely more on (majority-white) academic networks to identify job candidates and to rely more on stereotypes about academic productivity when choosing new colleagues.”

Uncertainty also may have led institutions to “cut hiring for programs and departments deemed dispensable, in fields with more people of color,” the study suggests.

COVID-19 and Faculty Diversity

Will the COVID-19 crisis have similar effects, the researchers ask? On the one hand, like the Great Recession, they say, the pandemic has led to sharp decline in job ads and hiring in the short run. Yet COVID-19 differs from the recession in that it may have very gendered effects, curbing women’s job prospects more than men’s due to childcare and school closures, virtual schooling, and “the disproportionate impact of these changes on women in academia, due to the continuing gendered division household labor.”

The “contours of the current crisis are also different,” the study says, in that Ph.D. cohort sizes have shrunk, and, significantly to issue of race, “because police violence in communities of color and the heavy toll the pandemic has taken on those communities have fueled a revival of the Black Lives Matter movement.”

Black Lives Matter “may focus attention on the issue of faculty diversity,” the study notes. “But if colleges and universities respond to the challenge as they have in the past, with diversity initiatives that do nothing to change hiring routines, crisis-induced uncertainty may again lead to reductions in the diversity of new faculty.”

Kwan Woo Kim, a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at Harvard University, co-wrote the study with his professor, Frank Dobbin, and two researchers at Tel Aviv University, Alexandra Kalev and Gal Deutsch. Kim said that he and his colleagues were “more disappointed than surprised” with their results, given that numerous other studies show academic institutions aren’t “fully objective when it comes to hiring and promoting scholars.” Interview-based studies, in particular, find that many academics still hold certain stereotypes against women and scholars of color, he said, such as that they are “not as competitive as their counterparts,” meaning white and male scholars.

Kim said it’s still early to predict how COVID-19 will affect hiring patterns, but he underscored the impact of the pandemic on gender. Early survey results certainly suggest that women academics “suffered from greater stress while working from home, and that they saw greater productivity declines during the COVID-19 crisis, possibly due to the gendered division of household labor,” he said, echoing his own study. Such data “all point to the prediction that women would have lost more ground during and after the current crisis. Would that be the case? We will know when the data come out.”

That said, Kim continued, it’s important for hiring committees and those in the decision-making processes around hiring -- meaning chairs, deans, provosts, chancellors and presidents -- to “remain vigilant not to give room for stereotypes or other types of biases against women and scholars of color, and to remind them that they may, consciously or unconsciously, rely more on stereotypes in making hiring decisions during uncertain times” -- the current crisis included.

Autumn Reed, assistant vice provost for faculty affairs at the University of Maryland at Baltimore County, leads her institution’s Strategies and Tactics for Recruiting to Improve Diversity and Excellence (STRIDE) program and recently wrote a white paper for and addressed the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Math on faculty diversity in the age of COVID-19.

Reed said that DEI must be framed as the necessity it is rather than a “want” that can be put on the back burner until the pandemic is a memory. Instead of an exception, she said, COVID-19 is a reminder that faculty diversity is a “duty of care” to society. Now and in the future, she added, DEI and social justice must be the “embedded” principles guiding college and university recruitment and retention.

“Now is the time to do more, not less, even if it requires doing more with less,” Reed said, echoing her comments to NASEM. Approaches include funding postdoctoral fellowship programs and cluster hiring initiatives while simultaneously promoting peer education among faculty members on DEI and departmental readiness.

Search committees must also plan how they’ll mitigate the impact of COVID-19 disparities in their recruitment efforts and interviews, as the pandemic has affected different groups differently, Reed said, and institutions must hold committees accountable. COVID-19 impact statements are one idea. And given that the pandemic-era job market is especially difficult, committees should use broad language in their job ads to attract a diverse pool of applicants. They could even consider hosting an online event or recorded webinar to recruit for an open position, rather than relying on conferences.

In each and “every step of the process,” Reed said, search committees should be asking themselves how a practice “does or does not foster DEI -- and adapt accordingly.” Otherwise, institutions risk “unwittingly reproducing inequality.”

Julian Vasquez Heilig, dean of the University of Kentucky’s College of Education, has found faculty diversity increased very little nationwide from 2013 to 2017, with large research institutions showing the least progress of all. That’s especially disheartening given that many institutions announced expensive diversity initiatives starting in 2015, beyond the time frame covered in Kim’s paper.

Yet within Heilig’s college, as of earlier this year, two-thirds of the recent faculty hires were from racial minorities -- meaning that a reversal of progress toward faculty diversity is far from inevitable.

Regarding Kim’s paper, and his and his colleagues’ warning about this current crisis and its potential impact on faculty diversity, Heilig said, “We are living in a post-George Floyd era where faculty and academic leaders are focused -- perhaps more than ever before -- on diversity efforts.”

Heilig’s college increased faculty diversity over all by almost 5 percent during COVID-19, despite a $2.4 million budget cut, he said, “because of continued university support and faculty hiring committees being intently focused on creating more diverse hiring pools.”

In terms of resources, Heilig said that other education deans he’s talked with of late report still having flexibility to pursue faculty diversity efforts. So successful diversity efforts will reflect “commitment,” he said, and not the mere availability of resources.