You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

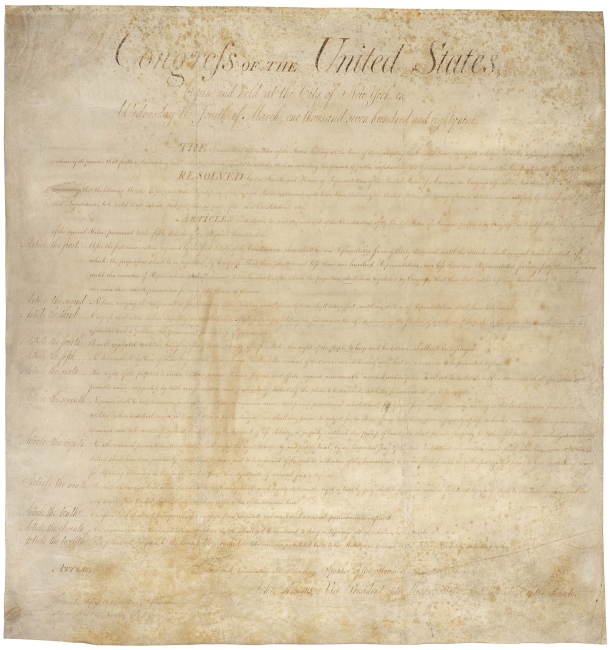

The Bill of Rights

National Archives

Last week, the University of South Carolina suspended a student for writing the n-word on a whiteboard in a campus study room. The university president explained that the student had violated the Carolinian Creed, which bars “racist and uncivil rhetoric.”

But in the United States, there’s another creed that’s supposed to take precedence over all the others: the Constitution. And the university -- not the offending student -- violated it.

So did the University of Oklahoma, when it expelled two students last month for leading a racist chant on a fraternity bus trip. The chant referred to the lynching of African-Americans, one of the ugliest chapters in our nation's history, and the students deserved all of the condemnation they received.

But our university leaders deserve censure, too, for their craven disregard of the First Amendment. Everyone has the right to speak their mind, no matter how much it offends yours. When Americans work themselves into a fine moral lather, however, freedom of speech is always the first thing to go.

Campus speech codes date to the mid-1980s, in the aftermath of several well-publicized racist episodes. Following the last game of the 1986 World Series between the Boston Red Sox and the New York Mets, drunken brawls erupted at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst between white Red Sox fans and black Mets supporters. At one point, a mob of 3,000 whites chased and beat black students.

After that, media outlets ran a spate of stories about racist incidents on campus, including a mock slave auction at a fraternity. It was never clear whether racial prejudice and harassment had actually increased during these years. But it made for good copy, with headlines like “Bigots in the Ivory Tower” and “Reagan’s Children: Racial Hatred on Campus.”

As the last item suggests, liberals were quick to blame the alleged rise in racism on Ronald Reagan and the so-called New Right. As conservative politicians stoked the fires of prejudice, the argument went, our campuses should remain bastions of racial equality and justice.

Enter speech codes. By 1992, fully one-third of colleges and universities had enacted some kind of speech regulation. The most famous one -- which became a model for many other measures -- was adopted by the University of Michigan, which barred “verbal or physical behavior… that stigmatizes or victimizes an individual on the basis of race, ethnicity, religion, sex, sexual orientation, creed, national origin, ancestry, age, marital status, handicap or Vietnam-era veteran status.”

But as a U.S. district judge ruled in 1989, when he struck down the Michigan speech code, the words “stigmatizes” and “victimizes” were notoriously slippery. “What one individual might find victimizing or stigmatizing, another individual might not,” the judge wrote.

A few years later, the University of Pennsylvania charged a student with violating its speech code after he pleaded with some partying African-American sorority members to keep down the noise. “Shut up, you water buffalo,” the student shouted. “If you want a party, there’s a zoo a mile from here.” In his native Israel, the student later explained, the term "water buffalo" referred to a rowdy person; but the black students interpreted it -- and his zoo remark -- as racial insults.

Penn eventually dropped the charges against the student and -- two years later -- it eliminated its speech code. But it was one of the exceptions. Most college retained their speech codes or added new ones, even in the face of judicial decisions barring such measures. Between 1989 and 1995, six courts -- including the U.S. Supreme Court -- examined university or municipal speech codes, and in every case the codes were deemed unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court’s 1992 decision struck down a St. Paul ordinance prohibiting hate speech. Inevitably, the court ruled, city officials would be called upon to decide what was truly hateful and what wasn’t. And that’s not a call that any of us should want our government making for us.

But that’s precisely what our campus speech codes require universities to do. In a recent survey of over 1,000 Jewish students on 55 American campuses, more than half reported experiencing or witnessing an anti-Semitic act or comment within the prior six months. Earlier this year, a Jewish student applying for a campus judicial board position at the University of California at Los Angeles was asked how -- as a Jew -- she could maintain an “unbiased view.” And at another U.C. campus, in Davis, Jewish students opposing an anti-Israel boycott measure were heckled with cries of “Allahu Akbar.”

Both episodes made national news, but they didn’t lead to any official punishment for the students who made the offending comments. Why should racist comments elicit penalties while anti-Semitic ones don't? And why should we allow our universities to discriminate between them when the courts have ruled that both types of speech are protected? We need to educate our students against bigotry without turning our backs on the Constitution. But first, we'll need university leaders with the courage to do it.