You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

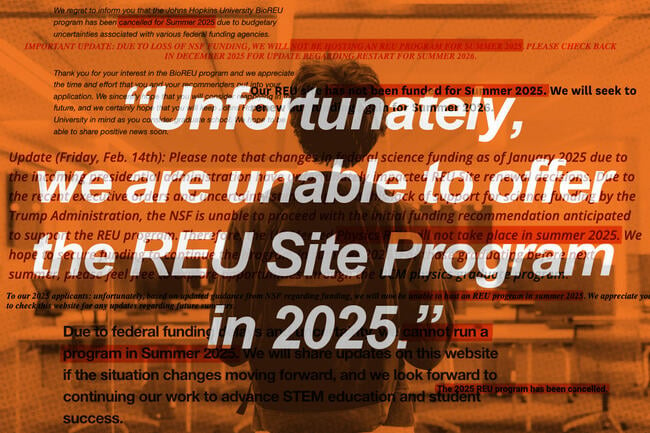

Leaders of at least a dozen REU programs have canceled their sites this summer due to uncertainty about NSF funding.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | ferrantraite/E+/Getty Images | REU websites and email communications

Saren Springer researches when and how embryos develop their arms and legs. But she didn’t always know she would be a researcher. Growing up in rural Minnesota and studying at a small liberal arts college with few labs on campus, her first exposure to research was watering plants for a graduate student studying the impact of runoff on plant growth—a cathartic routine that helped her adjust to the stress of college as a first-generation student.

Then, in the summer after her junior year, as she was second-guessing her plans to become a doctor, she was selected to spend the summer at the University of Connecticut. There, she would conduct research as part of the Physiology and Neurobiology Department’s Research Experience for Undergraduates, a program, funded by the National Science Foundation, aimed at helping students from colleges with a smaller research footprint experience world-class research at larger, more prestigious institutions.

“The research that I was able to do at my liberal arts was very surface level, just getting me exposed to the idea of research. But actually being able to answer some sort of question was something that I didn’t really get until I did the REU,” Springer said.

The experience offered “a glimpse into the actual career of becoming an academic researcher.” Now, Springer is a graduate student in that very same department, seeking a Ph.D. in physiology and neurobiology from UConn. But now it’s unclear if other students will be able to follow in her footsteps.

The department’s REU, which is one of over 1,300 such programs nationwide, won’t run this summer along with at least a dozen others—cancellations that have left students and professors alike worried about the loss of valuable research education.

REUs are typically funded on three-year cycles, and those up for renewal this year have found themselves caught in the headwinds of the Trump administration’s effort to curb federal spending and ensure programs align with the president’s priorities.

So far, many faculty leading REUs have either seen their proposals rejected or never heard back from the NSF. Others told applicants they weren’t sure if their REU would continue as planned and decided to hold off on accepting students until they knew more, according to emails shared on social media.

“If funding for these programs is cut, you’re losing an opportunity for students who wouldn’t normally be able to experience research in this capacity,” said Springer.

And that loss isn’t just going to impact the students themselves; some faculty who lead REUs are worried that losing research opportunities for today’s undergraduates will ultimately weaken America’s STEM workforce—and the nation’s place as a global leader in science and technology—in the long run.

“We have a shortage of domestic talent, and not because those people aren’t there. It’s not because we don’t have the best and the brightest among our own. It’s because we need efforts that recruit those students, that provide the support that might be needed in order for them to be successful,” said Keivan Stassun, a professor of astronomy at Vanderbilt University.

The NSF declined to provide comment for this story.

‘A Strong Pipeline’

The REU program was founded in 1987 as a way to expand access to high-level research opportunities for students at small institutions and community colleges (though in certain cases, students can participate in REUs at their own institution). Faculty leaders told Inside Higher Ed that, for many participants, an REU is their first time ever conducting research. And because the students typically receive a stipend, free room and board, and even funds to cover travel to their site, the program is broadly accessible, opening doors to students who may not be able to afford to take on other opportunities due to costs.

Improving access to these experiences is important, advocates for the REUs and other such programs say, because studies have shown undergraduate research is correlated with higher academic performance, retention in STEM fields and, eventually, entering science careers.

“The return on investment is huge because we’re training students in quantum technology and AI and cybersecurity and biotechnology—these are all things that REU programs support … these are all things that are federal priorities, and it’s just hard to square in my mind why we would intentionally cripple such a strong pipeline into those research and development areas,” said Tony Wong, an assistant professor in Rochester Institute of Technology’s School of Mathematics and Statistics who co-leads an REU focused on STEM education research that has run nine times over the past 10 years.

The program varies from institution to institution, but all sites focus on mentorship, professional development and exposing undergraduates to what graduate-level scientific research really entails.

One professor, who chose to cancel her REU site at a highly selective private college due to funding uncertainty, said her program prioritizes students with no research experience and takes on a “summer camp structure”—while also teaching the ins and outs of laboratory research.

“The goal of the program is to provide what we call an authentic research experience,” said the professor, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “And the nice thing about the summer programs is that it’s 10 weeks full-time, and so they’re really immersed in it. They get a research question that they can develop from the start, they can test, they feel ownership over. That’s the goal. And then they’re able to actually come up with findings and present those and it’s like the whole research process in miniature.”

Rejections and Uncertainty

Stassun, who leads Vanderbilt’s Physics and Astronomy REU, said that he heard from his department’s program officer at NSF in early January that the program was being recommended for funding—a common courtesy that typically means the grant is all but guaranteed to be successful and allows recipients to begin spending the funds before they officially come through.

But just last week, he received word that the Physics and Astronomy REU would not, in fact, be receiving funding for the first time since 2006.

That’s surprising to Stassun, given that the program’s “funding proposals [were] always ranked very, very highly.” The program is successful at educating future researchers, with at least 72 percent of its participants proceeding on to graduate education. It differs from other REU proposals due to the program’s interdisciplinary focus, partnering up with other Vanderbilt departments to give students more opportunities to solve real-world problems and learn about research-related careers outside academia. The program also works with the Frist Center for Autism and Innovation, which Stassun runs, to help support students in the REU who are autistic or otherwise neurodiverse.

Wong, meanwhile, said that he never heard either way about whether his site’s proposal had been successful this year, which led him and his co-lead to cancel this summer’s program without soliciting applications.

“These are kids that are trying to figure out what their summer is going to look like, and really what the next few years that their lives are going to look like,” he said. “We didn’t feel good about asking students to put in a ton of time, energy, and really put their hearts into these things when we didn’t know that we actually had something that we were able to offer them.”

According to a program director at the NSF who spoke on the condition of anonymity, multiple REU leaders were informed that they would be recommended for funding before President Trump took office, only for them to later be rejected, which is unusual. Although not all of the grants for REUs have been awarded yet, the program director said that it seems several of the agency’s divisions will only be able to fund around half the number of REUs that they normally would in a given year.

The cost of funding REUs is a drop in the bucket of the NSF’s yearly spending: In fiscal year 2024, NSF estimated that the program cost around $85 million across about 1,300 sites. The agency has an annual budget of about $9 billion.

The vast majority of each grant—at least 90 percent—goes toward students’ housing, travel and stipends. In some cases, the money also supports their research projects. Some REU leaders told Inside Higher Ed they take no compensation for running the program.

Now, students who were hoping for a coveted spot in an REU are worried about if the canceled programs will ruin their summer plans—and how changes to federal funding for research will impact their careers long term.

Xuliana O, a senior studying physics and biology at Virginia Commonwealth University, applied to a program at Johns Hopkins University that was later canceled, and another program announced it wouldn’t be happening just as she was about to apply.

While there is a chance she’ll land another position this summer, she is worried about the Trump administration’s cuts to funding more broadly.

“I’m thankful that I have experiences that would prepare me for grad school, but to see this amount of reduction in research education and training makes grad school seem like not an option,” she said. “It’s something that I’ve spent three years preparing for, and just to have that now seem more uncertain than it previously was doesn’t feel great.”