You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

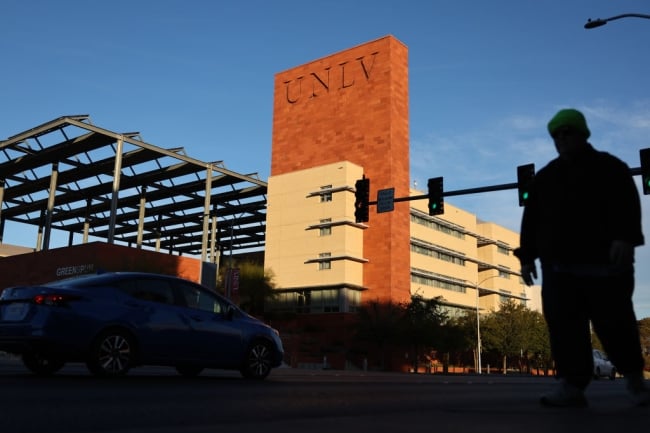

The current Board of Regents oversees all eight of the state’s higher education institutions, including the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Mario Tama/Getty Images

After fighting for nearly a decade about who should oversee Nevada’s higher education institutions, state lawmakers are hoping voters will give them the power to overhaul the current system, which includes an elected board of regents, when they head to the polls in November.

The state’s constitution has long called for a board of regents composed of elected officials, but lawmakers argue this rare structure gives too much power and not enough accountability to the 13-member panel—allowing the regents to see themselves on equal footing with the State Legislature and immune from oversight. But the ballot measure, known as Question 1, aims to put the regents on the same level as other executive agencies, in part by amending the constitution to remove references to the board.

Question 1 is the result of long-running tensions between the Legislature and the Nevada System of Higher Education’s chancellor and its regents. The chancellor and regents oversee the state’s eight higher education institutions: three universities, four community colleges and a research institute.

The system has churned through chancellors over the last eight years and seen a slew of high-profile controversies across their various tenures, for which the board has been blamed.

One chancellor allegedly attempted to mislead lawmakers as they made funding decisions. Another, along with the regents, pressured a popular university president to resign and caused several key contributors to withdraw or reconsider multimillion-dollar donations. And the latest chancellor left after just 19 months in the role, accusing the regents of creating a hostile workplace.

Local experts say these incidents, combined with a recent audit that found “inappropriate or questionable” use of students’ tuition dollars, have fueled distrust and led lawmakers to make some of the toughest COVID-era budget cuts for public colleges.

A group of bipartisan lawmakers says the answer to the system’s woes is to pass Question 1, which would also introduce regular financial audits and open the door to a new governance structure, likely one with legislatively appointed regents.

A similar amendment was proposed in 2020 and narrowly rejected by voters, but supporters, including local businesses, former higher education leaders and some faculty members, are backing it this time. They say the 2020 failure was a result of confusing language and pandemic distractions and are more optimistic for success this time around.

Former NSHE chancellor Dale Erquiaga, who previously opposed the ballot measure, told The Nevada Independent in September 2023 that something has to change.

“I think it’s time for Nevada to rethink how it governs higher education and what it expects of higher education, whether that’s the community colleges for workforce development, or the research universities,” he said.

But the regents who currently serve on the board and other opponents argue that allowing the Legislature to appoint board members could further politicize higher education and hurt academic freedom. They also note that many of the regents and administrators accused of mismanagement in the past are no longer in office, and therefore it’s unreasonable to let an old grudge drive a constitutional amendment.

Voters in Nevada aren’t the only ones who will weigh in on ballot measures related to higher education this November, but higher education experts will be watching Question 1 closely.

“Nevada’s a state, obviously, that there’s a lot of interest in just generally, because of the presidential race, and it’s very much a swing state,” said Tom Harnisch, vice president for government relations for the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. “So it’ll be just interesting to see how the voters feel.”

Eliminating an ‘Antiquated’ System

David Damore, a political science professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, said that the constitutional amendment is needed to rid the state of its “antiquated” system—a stance echoed by other supporters.

“If you read the Constitution, it says to have a popular elected board to govern the land-grant institution in Nevada,” he said. “What’s happened over time is that all of higher education was placed under that provision … This led to the idea that higher ed is a fourth branch of government, which was very well beyond the scope of what the framers of the Constitution intended.”

As a faculty member himself, and someone who has been advising legislators on higher education reform since Question 1 discussions began in 2017, Damore is fully onboard with the referendum and hopes that if it passes, university funding will rise.

“You had just nothing but negative stories coming out of higher ed for a long period of time,” he said. “What ended up happening was the Legislature got so frustrated that they used the only tool they had to try to rein in higher ed, and that was cutting the hell out of its budget.”

Other faculty members have also had it with the board. The Nevada Faculty Alliance Board, an AAUP affiliate union, voted last month to endorse Question 1 after staying neutral on the issue in 2020. Members are still divided on the issue—41 percent of participants supported the measure, 43 percent opposed it and 16 percent were undecided—but in the end the faculty union said that Question 1, while flawed, was the only path for change.

Carol Lucey and John Gwaltney, presidents emeriti of two different community colleges, have also said that the current board is antiquated and does not consider the unique needs of individual institutions.

“Each college and university has a different mission and each Nevada community has evolving needs, in order to meet the demands of its workforce and economy,” they wrote in a supporting memo. “There can be no one-size-fits-all approach.”

Protection From Politicization

But opponents still remain. Inside Higher Ed spoke to three regents and local reporters spoke to several others, all of whom stand against Question 1.

The regents say it is unclear how the ballot measure would address problems within the state’s higher education system in a way that normal legislation would not, and they argue that pushing the issue a second time is infringing on the will of the voters who already rejected the measure once.

In a 2023 legislative hearing about the amendment, Joe Arrascada, vice chair of the board, compared rehashing Question 1 to former president Donald Trump denying the results of the 2020 presidential election.

“This new resolution is blatantly questioning the voters’ will,” he said.

Laura Perkins, who is a board member but said she wasn’t speaking as a representative of the panel, argued that the amendment would create less oversight for higher ed, not more.

“Because there’s 13 board members right now, we can have a meeting in three days,” she said. “Anything that comes up, we can immediately have a meeting, discuss it and get all the cards on the table in a transparent manner in three days, whereas it takes a little bit more time to get through the Legislature … So that kind of defeats the purpose about more transparency.”

Perkins also said that tension between the board and the Legislature is “not a reason to make a change.”

“Right now, there’s only four [regents] that have been there for six years,” she said. “To keep the animosity going with brand-new members, that just doesn’t sound right.”

Others still, like Harnisch from SHEEO, and Mary Papazian, executive vice president of the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges, are hesitant to say whether the amendment and the governance changes that would follow would be positive or negative.

Although the referendum would nullify the guarantee of a board’s existence if it passes, the measure would not repeal any other existing laws, such as the current processes for electing regents. This means that though the State Assembly would be able to restructure higher education oversight, it would have to pass additional legislation to do so. And until it does, Harnisch said, it’s difficult to judge the outcome.

“It depends on … who ultimately appoints the people. What’s the role of the Legislature? And what’s the role of the governor?” he said. “Directly electing regents presents challenges, but we’ve also seen other models have challenges as well.”