You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Class Dismissed details how Harvard students of different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds weathered the pandemic and what university leaders can learn from what they went through.

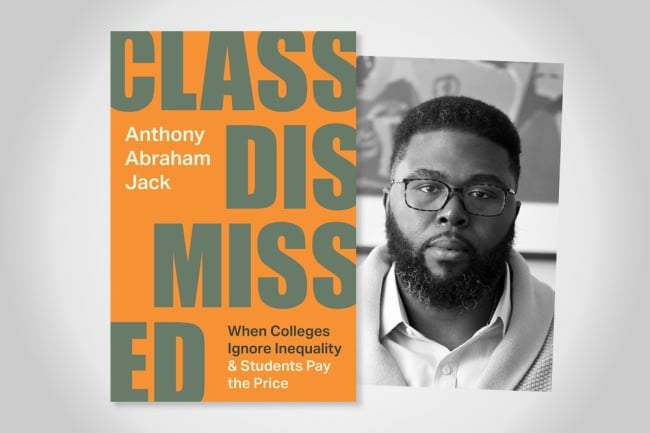

Book: Princeton University Press | Photo: Chris D'Amore

Highly selective universities have welcomed unprecedentedly diverse classes in recent years. That’s a laudable development, Anthony Abraham Jack argues in his new book, Class Dismissed: When Colleges Ignore Inequality and Students Pay the Price (Princeton University Press), but institutions lack understanding about the students they’ve recruited. And as a result, some of the country’s most well-resourced universities are often unprepared to meet the needs of those students—or worse, have policies and practices that actually work against them.

The book, published Aug. 13, suggests such blind spots were on full display when campuses shut down during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Based on interviews with 125 Harvard University undergraduates of different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds, Jack recounts the various ways students navigated the campus closure and the larger health crisis, depicting them as emblematic of broader inequalities. The book toggles between richly detailed narratives of these students’ lives during the pandemic and broader critiques and policy recommendations for how higher ed can serve them better.

Jack, an associate professor of higher education leadership at Boston University, is the inaugural faculty director of the institution’s Newbury Center, which provides programming and services for first-generation students. He answered Inside Higher Ed’s questions about his work with written responses, which have been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Your book takes an intimate look at the lives of students of different racial and socioeconomic backgrounds at the unprecedented moment when Harvard and so many other campuses shut their doors in response to the pandemic. Why did you want to zero in on that particular snapshot in time? How much can their stories tell us about universities’ approach to serving diverse students more broadly?

A: It was important to me to showcase the inequalities that universities were ignoring and that COVID made worse and more visible. I see Class Dismissed less about COVID closures and more about the gaps that existed long before them. Colleges continue to recruit, admit and enroll diverse student bodies—some marking new records for benchmarks—and yet so much of the support does not continue once students get to campus. And worse, some of the policies and practices that govern campus life are exclusionary and punitive.

For example, universities take a hands-off approach to on-campus work. They use once-a-semester job fairs and websites like Handshake to do the bulk of the work. But this ignores how social class shapes students’ strategies for finding work. High impact positions like course and research assistant roles are often not posted at all; rather they are handed out in office hours to those students comfortable being in those spaces and building those more intimate relationships. What results is a class-segregated labor force on campus, with lower-income students being more likely to have jobs in food services and janitorial. These are important, skill-building jobs. But we also know that some jobs pay more than money. Recommendation letters are the coin of the realm. Moreover, when COVID came and shut campus down, students in research and teaching were able to keep working, even increasing their hours, [while] those who worked in manual labor positions lost out on hours.

While lockdown exposed the unevenness, students’ stories highlighted the reality of being a member of an unprecedently diverse class. The answer to many of colleges’ toughest questions can be answered by talking to students. I fundamentally believe that in their stories there’s a blueprint to the future. Why create policies in a vacuum?

Q: Your book describes students living vastly different realities during the pandemic, some returning to homes with ample space and quiet, with opportunities to travel, do research and gain work experience, while others returned to places that made them feel unsafe and they lost jobs. Which disparities stood out to you as the most overlooked by university leaders?

A: Yes. During the pandemic and university closures, there were students who rented Italian villas while others lived on couches in the kitchen. There were students who ran through empty national parks that were closed to the public but not to them because their houses were nestled next door while others were too afraid to jog outside even before the streetlights came on. Poverty and privilege were on full display in the book. The thing I want universities to grapple the most with is neighborhood inequality. And how students don’t [just] come to college, [their] communities do too. Students no longer wait for texts or updates on social media about when problems arise at home. Some have taken to using apps like Citizen to track stabbings, fights and other forms of disorder around their family. This taxes lower-income students who are already grappling with satisfying the old responsibilities of home and the new role of student. And yet, our mental health services are often woefully underprepared to deal with the consequences of redlining, land theft and other sanctioned practices that leave generational scars on communities. We focus on study skills while many students are in survival mode.

I studied college-leave policies to further underscore how universities’ ignorance of place plays a critical role in undermining diversity efforts and student success. When students are mandated to leave, often because of the burden of home weighing on them, we send them away with a laundry list of items that are near impossible to complete. For example, holding down a full time job. If a student is from a rural community or a reservation, two places that have been ravaged by economic inequality, what jobs are they to get when members of their own family struggle to find employment? Will it be a job that the school accepts as enough? And as if that isn’t enough, you must get a letter from your supervisor ascertaining your readiness to return, which means divulging that you have been sent away from school. Why require so much of someone so vulnerable?

Q: You argue in Class Dismissed that when students enroll, “what happens outside the college—in their families, in their communities, and in the nation—permeates the campus.” What do you hope university leaders take away from the book, in terms of how institutional policies can better address how students’ lives beyond campus affect their time in college?

A: The big push is to get colleges to understand where students come from, and stay connected to all their college years, to forge new policies that govern campus life. One thing that I think will help us is to retire the metaphor of the “college bubble,” not just in everyday speech but in how it seeps into campus policy. The saying is not just outdated, it was never true for those students who come from families and places that require a lot of them.

Q: Since you interviewed students, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against race-conscious admissions and multiple states have passed bills that take aim at DEI work on campuses. How do you think those currents affect the work you’re proposing colleges and universities undertake to better serve the diverse students they’ve enrolled?

A: I think it makes the work even more needed. Colleges are now doubling down on recruiting lower-income and first-generation college students. These were the very students who were the most exposed to the worst of what the pandemic brought to the fore. Importantly, my work is about addressing what does it mean to live in poverty’s long shadow even when at the ritziest of universities. It is like universities treat diversity like buying a house except they only focus on the down payment of financial aid. They forgot about the closing costs. And, to make matters worse, they don’t budget for all the hidden costs, especially those that tax students most acutely.

Q: In the book, you mention your own experience as a low-income student at Amherst College stranded on campus over spring break with the dining hall closed. How did your experiences as a student inform your research?

A: I am a forever first-generation college student. My path to research will forever inform my perspective. The emails that announced closures at Harvard and at colleges around the country transported me back to my helpless, broke first year at Amherst College. I had no plan other than to work to earn money to eat. I was scared and angry. These emotions arose again that day in March 2020. And I channeled all those emotions into this project. I knew I wanted to share students’ stories, but not just to share them. To hold universities feet to the fire, forcing them to learn from what students went through before and during closures. That is the only way they will learn and, hopefully, change.

There is often a push in research to remove “I” statements. This is a mistake. I didn’t see myself in the research that was being done on those who look like me and come from places like me and attended schools like me. Missing perspectives lead to gaps and biases, undermining knowledge development and limiting progress.