You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

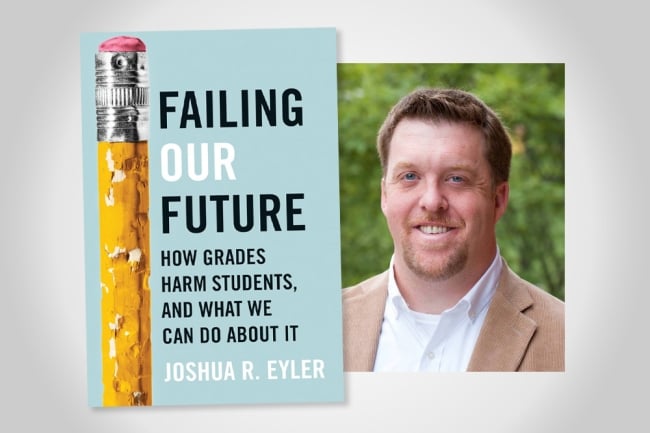

Failing Our Future, which comes out Aug. 27, explores the issues with grading and what alternatives exist.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Johns Hopkins University Press, Joshua Eyler

Joshua R. Eyler is no stranger to alternative forms of grading, which he has been utilizing in his own writing classes for over a decade. But it wasn’t until he was composing his previous book, How Humans Learn (West Virginia University Press, 2018), and investigating the positive role that failure can play in the learning process that he realized how deep of a hindrance traditional grades—which can discourage students from being anything less than perfect—can be.

That was the initial inspiration for his forthcoming book, Failing Our Future: How Grades Harm Students, and What We Can Do About It (Johns Hopkins University Press), which will be published Aug. 27. In it, he revisits a question that professors, students, administrators and those outside the academy are always eager to discuss: Do grades help or hurt students?

Currently the director of the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at the University of Mississippi, Eyler falls solidly on the “hurt” side of the contentious debate at a time when the alternative view seems to be as pervasive as ever, with critics, especially on the right, arguing that alternative grading systems are a sign that American meritocracy is dead.

In an interview with Inside Higher Ed, edited for length and clarity, he explained how a world without grades—or, at least, one with different grading methods—could be a better world for all.

Q: The questions and controversies that you explore in this book are perennial issues. Why did you want to write about grades in the current moment, and what new perspectives were you eager to bring into the conversation?

A: A few years ago, I was finishing How Humans Learn, and I was writing a chapter for that book on failure as a key component of the learning process. I kept finding research about grades and all the obstacles that grades set up for students. So although I wasn’t really focused on grades, necessarily, in that chapter I kind of put a pin in that as a topic that I might want to come back to.

Over the next few years, in between that and the vast number of people in my sphere who I saw experimenting with new ways of grading, I thought, this is really something to explore. So I started to dig into it and found very quickly that the academic issues with grades, although there are many, are in some ways the least significant problems with grades. If we’re talking about new angles, some of the ones that I really focused on in the book include the ways that grades reflect and magnify inequities that are and always have been a part of the American educational system. One that I’m personally really invested in is the role that grades and academic stress play in the mental health crisis for teenagers and young adults.

Q: What can schools be doing to curb academic anxiety, whether it’s related to grades specifically or otherwise?

A: What they are doing is often criticized for being sort of surface-level solutions, or at least fundamentally inadequate solutions. So, a lot of a lot of the response to this has been, hire more counselors for the counseling center. Of course, there’s nothing wrong with that—in fact, that’s great. Hire more counselors. But that alone does not address the fundamental issues of academic stress—and grades in particular—and the effect that they’re having on students.

If we’re looking specifically at the academic stressors, and grades as a part of that, we really have to take a look at the role that the classroom plays: How is the way that we are giving grades and the kinds of models that we’re using in the classroom contributing to the stress? And are there other kinds of models for grading that would relieve the pressure valve on students?

I don’t think that there’s anyone on either side of this question who would deny that grades are extrinsic motivators … I think where people tend to disagree is how significant a problem that is.

—Joshua R. Eyler

And the answer to that question is yes, there are, and some of the alternative grading models that faculty are experimenting with in the classroom are designed specifically to relieve some of the pressure on students and to reorient their relationship with grades. Standards-based grading, contract grading, collaborative grading: These are all different ways of giving grades, because we acknowledge that most of us still work at institutions that require us to give grades, but they do so in a completely restructured way.

Q: You talk a lot in this book about how grades de-incentivize students from really having an internal motivation for going to class and learning. That feels especially relevant now, as professors are talking more and more about students being really disengaged. Is there a way to improve students’ engagement without the incentive of grades?

A: I don’t think that there’s anyone on either side of this question who would deny that grades are extrinsic motivators. The research is just so clear that grades are rooted in behaviorism—they are rewards for a particular action. They are the candy. They are the prize at the end of the race.

I think where people tend to disagree is how significant a problem that is. In this moment, in particular, with the levels of disengagement that people are noting in the classroom, some folks who are against grading reform will use their extrinsic nature to claim that that’s why we need them, to say, “We need grades to make sure that students are showing up in class. We need grades to make sure that they’re doing the work. If we don’t have grades, none of those things will happen.”

I’m enough of a realist to admit that, in some cases, that may be true. What we do know about extrinsic motivators is that they work. But they work in situations where what we are valuing is compliance. So, yes, it is true that if you have extrinsic motivators, you can shape people’s behaviors to say, “Come to class and turn things in on time.” But what an extrinsic motivator like grades can never do is ensure that a student will actually learn once they’re there. That depends truly on intrinsic motivation.

If learning—and meaningful learning—is our goal, we have to find ways to elevate and cultivate intrinsic motivation.

Q: There has been a lot of pushback to this from people who feel like institutions don’t reward hard work anymore. Do you have a response to that idea?

A: My response to the rigor and academic standard question has always been the same: There’s nothing inherent to a letter grade or a number grade that is uniquely intended to be able to measure academic rigor or standards. In other words, there’s nothing about a grade that allows it to be the only way to demonstrate that. You could much more easily and more effectively demonstrate high standards to a student—and that they have met those standards—through feedback, not a grade. The idea that we need grades to somehow preserve standards and rigor is false.

Q: What grading alternatives have you tried personally, for your classes?

A: I’ve tried a bunch of different ones, actually. I started maybe 10 years ago, moving in this direction with portfolio grading—which is widely, widely used in writing programs, arts, lots of different kinds of disciplines—where students work all semester to refine their writing, write a reflective introduction, and then it’s the portfolio that gets the bulk of the grade at the end of the semester. You give them a lot of chance to revise and experiment over the course of the semester.

[Grades] are at most a reflection of student progress on the individual goals set by one instructor for a particular course; they’re not a universal declaration of knowledge gained in a particular field.”

—Joshua R. Eyler

That’s how I started, but I have used contract grading, especially with graduate courses that I’ve taught. Predominantly, over the last five to seven years or so, it’s all been collaborative grading. The students self- assess, they propose their grades and I meet with them to talk about those at the end of the semester.

Q: When you’re looking at alternatives to grading, what are the top goals of those models?

A: I’m glad you asked this question because it gets into the question of measurements. What is it that grades are actually doing, anyway, even in a traditional grading system? I think a lot of the reasons people hold so tightly to grades is because they have this veneer of scientific objectivity. But what we know from a host of research, at this point, is that grades have never been objective measurements of learning or of achievements. They are at most a reflection of student progress on the individual goals set by one instructor for a particular course; they’re not a universal declaration of knowledge gained in a particular field.

What the alternative models do is they say, the learning that happens over the course of the semester will be highly individualized for each student in that class. What a lot of the models really seek to do is to reflect the fact that learning is a very complex process that unfolds at different rates for different students, and that traditional grades penalize many students for not being able to learn as quickly as others.

Q: Do you see any future or any version of this where grades and other strategies work in tandem?

A: I do give some examples in [Failing Our Future] of folks who are initially in learning environments because they had to get a grade or they needed a course for their GPA and came to really enjoy the subject or, once they were there, became motivated for other things. So, yes, it is certainly possible. In fact, I have had experiences myself as a student where I didn’t think I wanted to take a course, but I needed it and had to get a good grade for my GPA but came to really enjoy the subject matter.

So, it is possible, but you don’t want to design an entire educational system based on that possibility. Because, No. 1, it may not happen every time, and No. 2, for some students, it will never happen. So, you have to acknowledge the possibility of it while building pedagogies and curricula based on the reality that learning depends on much more on intrinsic motivation.

Q: In your perfect version of this, is there any room for grades?

A: That’s the big one: What’s the endgame? Is it no grades, or is there a role for grades? I am of many minds about this question. Even in the epilogue of the book, I sort of go in two different directions. One is the reality of, we can’t wave a magic wand and get rid of grades tomorrow, right? So, within that, what’s our goal? Even as we might dream of educational systems that are free of grades, for me, the immediate thing that we can use this research to strive for is a reorientation of grades: being able to use different kinds of grading models, to put the emphasis much more onto students and the learning that we hope that they are building along the way.

A lot of the alternative models really do that. The traditional grading models are not built to prioritize learning; they are built to evaluate a particular moment of a student’s academic life at a particular time. What we could imagine, in the shorter term, is something we’re already seeing. Some colleges and universities are dropping grades for first-year students; UC San Diego is building a writing program that is collaboratively graded. We’re seeing those kinds of reforms, and that, to me, is the wheels in motion of the kind of progress that I’m talking about in the book.