You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The annual synod, a gathering of Christian Reformed Church leaders, brought a controversial directive for Calvin University.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Ejd24/Wikimedia Commons | Documents: Christian Reformed Church of North America

Calvin University is under pressure from its owner, the Christian Reformed Church of North America, to re-examine a process by which professors can formally disagree with aspects of church doctrine.

The directive comes after multiple professors submitted official disagreements—called a “confessional-difficulty gravamen,” or, in plural, “gravamina”—with the church’s increasingly hard stance against same-sex relationships in recent years.

Some professors worry the church’s charge to review the process, and bring it into “alignment” with how the same process works for clergy, could quell faculty dissent on the issue and even cost LGBTQ-friendly faculty members their jobs.

“Calvin has always held in this beautiful tension a serious and devout approach to faith as well as intellectual rigor and curiosity,” said Debra Rienstra, an English professor who’s taught at the university for more than two decades. “I hope that we can continue to fulfill that mission, because that beautiful space of tension is very fruitful. It’s very needed.”

Seeking ‘Alignment’

Leaders of the Christian Reformed Church, a Calvinist Protestant denomination with Dutch origins, delivered the review order as a part of their annual synod this summer, where they gathered to discuss church matters, including gravamina. The gravamen process is mostly intended for clergy to report any qualms they have with particular church doctrines that may interfere with their work. Calvin faculty rarely use this process but are still subject to it, given the university started as a seminary and remains owned and operated by the denomination.

The synod concluded this summer that the sole goal of confessional-difficulty gravamina should be to allow clergy to “express and then work through” temporary doubts about a point of doctrine—not to report a long-standing reservation with an interpretation of church teachings, as some have understood it in the past. If a clergy member can’t reconcile an internal disagreement within three years, they need to resign, according to the synod.

Beyond just clarifying this process for clergy, church leaders ordered Calvin to bring the faculty gravamina process into “alignment” with theirs.

The Calvin University Board of Trustees has a year to report back to the synod about its gravamen revision plans.

“There are no immediate changes to our policies and procedures,” John Zimmerman, Calvin’s associate director of public relations, said in an email. “We’re just beginning the process of refining and updating those procedures per Synod’s directive, and we will be communicating about that process with faculty as it unfolds over the coming months.”

Fears for Faculty Expression

David Koetje, chair of the Faculty Senate at Calvin, said that professors typically submit gravamen to the Professional Status Committee, made up of professors and administrators, who determine the possible “implications” of a professor’s dissent and “whether any stipulations should be placed on that faculty member for their continued employment.” But the university has a “long history” of allowing disagreements to stand if they’re related to “disputed matters” not considered core principles of the faith, he wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed.

“Our process at Calvin has served for decades to actually facilitate honest academic examination of beliefs and assumptions,” Koetje said, adding that he believes this is critical to producing “scholarship that integrates faith perspectives.”

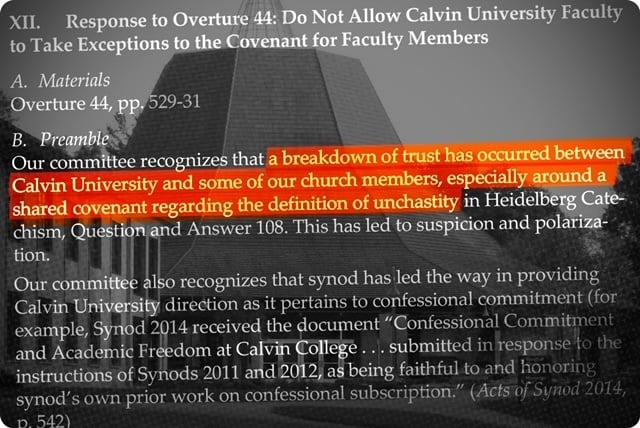

Church leaders made it no secret that their order is intended to address pushback on its homosexuality stance. Documents from the synod say there’s been a “breakdown of trust” with the university over the church’s current understanding of “chastity.” That is, in 2022, the synod moved to define same-sex relationships as a breach of chastity and elevated this interpretation to “confessional status,” meaning all clergy or faculty at church-owned institutions ostensibly have to toe the line. This caused an uproar among some Calvin faculty members and students. After a failed appeal of the decision in 2023, at least a dozen Calvin professors reportedly submitted gravamina expressing their dissent.

“The synod imposed a very conservative and very restrictive interpretation to this part of the doctrinal standards, one that had never been there before,” said James Bratt, a professor emeritus of history at Calvin. “It naturally rubs a lot of faculty the wrong way in terms of their personal, ethical viewpoint” and raises concerns about what they could teach in the classroom in fields like sociology, psychology and biology. It’s also Bratt’s view that church leadership has been trending in a more politically conservative direction.

What will happen to professors who previously wrote gravamina is unclear, but some at Calvin fear the worst.

To Bratt, the best-case scenario is that the university’s board finds some way to maintain the status quo. The worst-case scenario is faculty members who wrote gravamina would need to find new jobs. Another, still unappealing possibility is that only new professors will face restrictions on whether they can formally disagree with church doctrine, he said.

‘Fault Lines’ Over LGBTQ Issues

Kevin Timpe, William H. Jellema Chair in Christian Philosophy and philosophy department chair at Calvin, said faculty opposition to the church’s stance on LGBTQ issues is treated differently from other kinds of disagreements. He recently drafted a gravamen about it.

For example, he noted that he’s previously done academic work on the role of free will in Christian theology that comes to different conclusions than church teachings. He said he made that difference clear in his books, his application to the university and in his tenure documents. He was never asked to submit a gravamen. But in recent years, LGBTQ-affirming professors were encouraged by administrators to formally report their dissent, he said.

“Some of the propositions in the confessions are getting a lot more scrutiny than other parts, in ways that seem to track with contemporary American political and religious fault lines,” he said.

Timpe is “very concerned” about the uncertainty of what might happen to him if he submits his gravamen. The church’s recent stance against homosexuality and transgender issues has also made him guard his words when he teaches his philosophy of gender classes. And he’s already found, as department chair, that it’s difficult to make hires, partly because candidates fear they can’t be at odds with the church on LGBTQ relationships.

The university’s own track record on LGBTQ issues is mixed. On the one hand, Calvin has an active student group for LGBTQ students, called Sexuality and Gender Awareness, that regularly gathers and hosts events. An FAQ about LGBTQ students on the university’s website asserts that sex belongs in the context of heterosexual marriage but also promises students “LGBTQ+ persons are treated with respect, justice, grace and understanding in the Spirit of Christ” and being gay isn’t a sin. Calvin had its first out, queer student body president in 2021.

Two years ago, however, Calvin disaffiliated with its Center for Social Research after one of the center’s employees, Nicole Sweda, married her girlfriend. The move allowed her to keep her job without violating university policy against same-sex marriages, though she ultimately quit to be able to speak more freely about what had happened. But Calvin did end the contract of the professor who officiated Sweda’s wedding.

A ‘Little More Combative’

Jonathan S. Coley, an associate professor of sociology at Oklahoma State University whose research focuses on LGBTQ policies at Christian colleges, said his overall perception of Calvin has been that it’s conservative but relatively tolerant of LGBTQ students and the professors who support them.

He noted that evangelical institutions vary, but many Christian colleges allow professors and students to outwardly disagree with church doctrine on same-sex relationships, including nearly all Catholic colleges and United Methodist–affiliated institutions, before the United Methodist Church recently changed its stance on same-sex relationships.

However, Coley’s noticed what feels like an uptick in cases in which faculty and staff members have been fired from evangelical colleges and universities over friction with their stances on LGBTQ issues. There seems to be “a trend of evangelical Christian colleges and universities being a little more combative about LGBTQ issues and other social issues than they had in the past.”

Downstream Effects

Crystal Cheatham, associate director of the Religious Exemption Accountability Project, a group that advocates for LGBTQ students at religious higher ed institutions, said that when Christian colleges crack down on faculty dissent on these issues, queer students end up suffering.

“It kind of trickles down,” she said. When supportive faculty “are no longer there to actually protect these students, they’re vulnerable to their peers, they’re vulnerable to getting bullied because of the culture.”

Helen Groothuis, a Calvin alumna whose parents and grandfather also attended the university, said supportive faculty members played a major role in making her feel comfortable as a bisexual student.

“The reason it’s important for queer alumni to be vocal about what is happening is because of the students that are there now,” she said. “I think of my little queer self and trying to navigate that on my own, and in an environment that by all accounts was more accepting than it is today.”

Groothuis added, “One of the most important things for me was having those figures of authority on campus that you knew it was safe to talk about these things with.”