You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

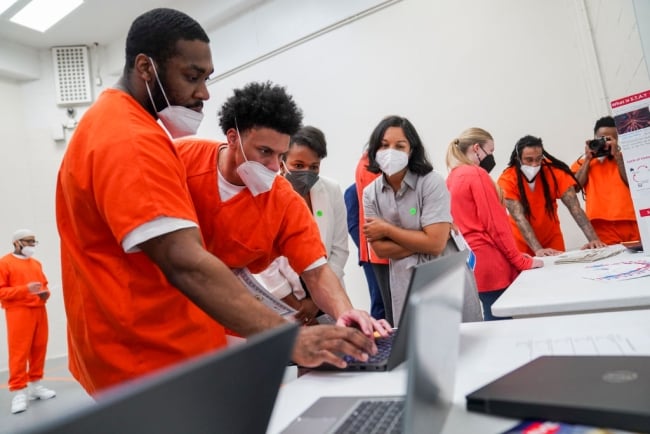

Students from Brave Behind Bars, an introductory computer science program for incarcerated people, talk about their projects during graduation at the D.C. Central Detention Facility in Washington, D.C., on Sept. 8, 2022.

Carolyn Van Houten/The Washington Post/Getty Images

A decision by Congress to restore Pell Grants to incarcerated students took effect last summer, a win for students and their advocates after imprisoned people attending college were barred from the federal financial aid for almost three decades.

A year later, colleges and corrections agencies have made significant strides toward launching new Pell-eligible programs and expanding existing programs under new federal regulations. But current programs still have work to do to better serve incarcerated students, according to a recent report by the Vera Institute of Justice, a research and policy organization focused on criminal justice issues.

The report offers a “snapshot” of colleges’ progress toward creating new Pell-eligible programs and evaluates the “quality, equity and scale” of current college-in-prison programs at a time when they’re poised to grow. It finds that many programs meet important quality benchmarks, such as employing qualified professors, but fall short on other key measures—including some required by new federal regulations—like access to academic advising.

“This is, to our knowledge, really the first report of its kind,” said Ruth Delaney, director of Vera’s Unlocking Potential initiative, which supports the development of college-in-prison programs. “There’s almost no national data on college in prison” and “even less research attempting to measure performance of those programs.”

The report is based on surveys conducted at corrections agencies and 140 higher ed institutions operating academic programs in 47 state, territory and federal Bureau of Prisons facilities, collected between November 2023 and March 2024. In total, 153 colleges and universities offered programs during that period under Second Chance Pell, a pilot program launched in 2015 to allow incarcerated students to access Pell Grants in select programs. The report scored each jurisdiction, or system of prisons, as “adequate,” “inadequate” or “developing” on 15 different metrics, including how easily credits transfer between higher ed institutions and the availability of library and research resources.

“We’re trying to establish a floor” for what it means to be a quality program in prison, said Delaney. “What we really want to be thinking about in the future is what the ceiling could be.” Programs should be “really worth the investment of incarcerated students’ limited Pell funds.”

Progress Toward Pell Eligibility

New proposals for Pell-eligible programs are currently making their way through a multilevel approval process. Under recent federal regulations for Pell eligibility, college-in-prison programs have to be approved by state corrections agencies, the federal Bureau of Prisons or a sheriff, as well as an accreditor and the U.S. Department of Education.

The report notes that all states, Puerto Rico and the Bureau of Prisons have now set up processes to review Pell-eligible program proposals, which wasn’t the case a year ago. At least 50 colleges new to such programs have received approval from corrections agencies this year, Delaney noted. So far, only one new program has been reviewed and received final approval from the Department of Education, a communications bachelor’s degree program through California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt, at Pelican Bay State Prison.

Delaney said that while such bureaucratic processes move slowly, the numbers are encouraging and show “a lot of enthusiasm” among colleges and corrections agencies to expand academic offerings in prisons at a time when “there’s still so much interest among students and unmet need.”

The report emphasizes that at least 45,000 incarcerated students have enrolled in college through Second Chance Pell, and those students earned upward of 18,000 credentials. Yet they make up only a fraction of the estimated 750,000 people in prison eligible to enroll, according to the report. And the majority of those people, about 70 percent, indicate in surveys that they’re interested in pursuing higher education. Prison populations are also disproportionately people of color; about 32 percent of prisoners are Black and 23 percent are Latino or Hispanic, even though less than 14 percent of the U.S. population is Black and only 19 percent is Latino or Hispanic, the report noted.

Erin L. Castro, associate dean for prison education pathways for undergraduate education and director of the Research Collaborative on Higher Education in Prison at the University of Utah, said she expects to see “sharp rises in both the numbers of colleges and universities deciding to serve incarcerated students and the numbers of incarcerated students who enroll.” At the same time, she said, “there are a lot of questions that remain unanswered” regarding how best to serve them.

Castro, who is also an associate professor of higher education, said the report starts to answer some of those questions and addresses long-standing calls among researchers and advocates for “some kind of framework for quality and for equity and for parity of outcomes.”

Room for Growth

The report finds cause for both celebration and concern when it comes to the quality, equity and scalability of existing college-in-prison programs.

On a positive note, most jurisdictions have established policies to ease credit transfer between higher ed institutions, according to the report. Almost all provided instructors with the same range of credentials as those who teach in college programs outside prisons and gave students opportunities to interact with professors face-to-face, as opposed to only remotely.

However, many of the colleges surveyed couldn’t ensure that students could continue their education after release. In addition, 11 of the jurisdictions offered programs in men’s prisons without a counterpart in women’s prisons. Most jurisdictions also gave students less than “adequate” access to library and research materials, academic and career advising, and technology to improve their education and build digital literacy skills.

Castro noted that limited technology access, while common for incarcerated students, can have far-reaching impact on their futures after release. Learning skills like how to run a Zoom call or use a learning management system such as Canvas are critical for helping them secure jobs or continue their studies outside of prison.

“It’s absolutely an equity issue,” she said.

Stanley Andrisse, executive director of From Prison Cells to PhD, an organization that helps people who have been to prison start careers, said it’s critical that the programs establish plans to help students with re-entry. That can include connecting them with local community organizations to assist with housing and job-readiness skills and making sure not only that their credits transfer to a college’s other campus but also that they can finish their current programs after their release.

Andrisse, formerly incarcerated and now an assistant professor and endocrinologist at Howard University’s College of Medicine, noted that universities aren’t used to providing re-entry support as a part of student services.

“This is not what they generally think of, and that’s not a bad thing,” he said. But “they should be partnering and looking for outside sources to help them think about doing this better”—particularly formerly incarcerated people.

The report also finds that programs aren’t reaching enough of the incarcerated population. In 24 jurisdictions, current college-in-prison programs enrolled fewer than 5 percent of people eligible and interested in higher education, while another 16 jurisdictions only enrolled between 5 and 9 percent of those people.

Andrisse added that it’s important to remember some prisons don’t have Pell-eligible offerings at all.

“There’s still work to be done in this idea of Pell for all,” he said.

The findings suggest that programs may need to make changes to stay in compliance with federal regulations. After two years of operation, each Pell-eligible program will have to undergo a “best interest determination,” a quality assessment by corrections agencies. They’ll be judged on four metrics, including how credit transfer, instructor credentials and academic and career advising compare to what’s available on colleges’ other campuses, and whether students can easily continue their studies upon release.

But colleges should aim to surpass those standards, Castro said, and use research like Vera’s to do so.

“If we want students to have high-impact experiences, if we want students to have high levels of student engagement, if we want students to have transformational undergraduate experiences and if we want them to get well-paying jobs with dignity and respect, we on the higher ed side, we have research to tell us what kinds of experiences students need,” she said.

Delaney said one of the main takeaways of the report is that college-in-prison programs need not just high-caliber academic offerings but more robust student support services.

“We’ve learned through Second Chance Pell how to provide college courses in prison,” she said. “And the next step we need to take is to figure out how to deliver all of the experiences of college.”