You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Robert Alexander/Archive Photos

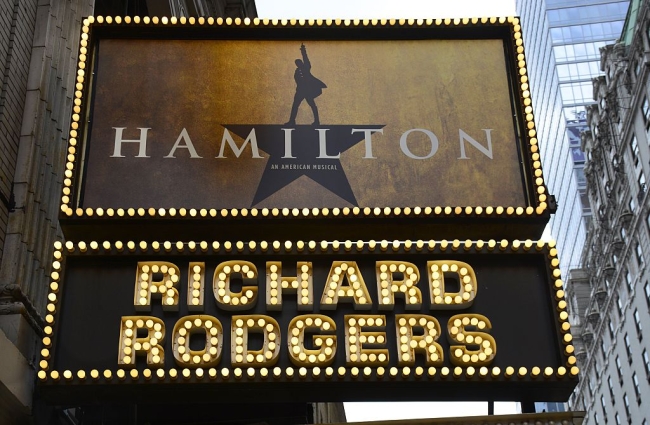

“Wrote My Way Out”—a song by Lin-Manuel Miranda also featuring Nas, Dave East and Aloe Blacc—represents writing as a means of upward mobility, offering a way out of poverty, loneliness, injustice and squalor. It was as simple as “pick[ing] up the pen like Hamilton,” they assure us on a track from The Hamilton Mixtape.

Writing your way out was similarly presented to me in graduate school in the early 2000s as a strategy for professional success. Sure, my first job might be at a higher education institution that faculty members at the Ivy league university where I completed my Ph.D. would deem undesirable—a capacious category that included anything other than a top research university or maybe an elite selective liberal arts college. Not to worry, I was told. I could always write my way out of Dodge and into a better position.

I remember attending a professionalization workshop as a graduate student where I sat, rapt, in a room full of my similarly engrossed peers listening to a full professor who was a single mother and person of color. She was telling us how she had written her way out of a tiny, financially precarious religious college, moving on to a large public university and from there to her current position in our department. At the time of the workshop, I was only vaguely conscious of how utterly anomalous her trajectory was—that for every person who managed to write their way out of an “undesirable” situation and into the Ivies, hundreds more must surely have stayed put, whether content with their position or not. And the professor’s inspirational story simply confirmed the message that I’d already begun to internalize: that publication was the primary criterion of professional success and the only means of professional mobility.

Comparing the ascent of a star professor to the story of a young man’s escape from the projects related in “Wrote My Way Out” might seem wrongheaded. But the same fantasy of individual agency, the belief that talent and hard work overcome any circumstances, underpins both narratives. It’s the persistence of this fantasy as much as the entrenched academic snobbery of the star professor’s story that bothers me almost two decades later. Even if higher education were the meritocracy it purports to be, this fantasy would be problematic. It places the onus of betterment and advancement on the individual rather than the collective and suggests that systemic problems are to be transcended rather than fixed. Faced with budget cuts? Bullied by your chair or dean? Contract not renewed? Teaching load too high? Class sizes too large? Denied promotion? Maybe you could write yourself out of that situation.

From the earliest stages of graduate education, future faculty members are trained to look out for themselves rather than to work collectively to solve problems in ways that would improve working and learning conditions for an entire department or institution. Here, Miranda and his team have us beat. At least they wrote their way out for the greater good. As Nas explains in the song’s outro, “I thought that I would represent my neighborhood and tell their story, be their voice in a way that nobody has done it. Tell the real story.” In higher education, it is a rare person who manages to write their way out and up the ladders of prestige, but it is even rarer that they use their success to tell their real story and advocate for those on the bottom rungs.

Perhaps one of the factors contributing to widespread burnout and demoralization among faculty members is that the fantasy of self-determining professional mobility is no longer tenable—that it’s dawning on people that, in fact, there’s virtually nowhere to go, no matter how much you publish or how impactful your research. I finished my Ph.D. a few years before the Great Recession of 2008 wiped out most of the jobs in my field, making it more difficult than ever to write your way into any kind of permanent position, let alone use writing as a strategy for professional mobility. Yet the myth that really good scholars will rise like hot air on the merits of their work has not disappeared nearly as swiftly as the tenure-track jobs—even though we increasingly recognize that those who count as “really good” are often just really privileged.

I’m left wondering how those of us who were socialized to believe that professional success is a matter of individual agency and a reflection of individual talent might cultivate a different mindset in future generations of scholars. Can we learn to understand collective problem-solving or institutional reform as accomplishments that are as valuable as publication? Can writing become a practice that helps us thrive in place? When writing our way out is no longer an option—and for many people, it has never been a viable one—what strategies can we use to turn an “undesirable” position into one we can live with?