You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

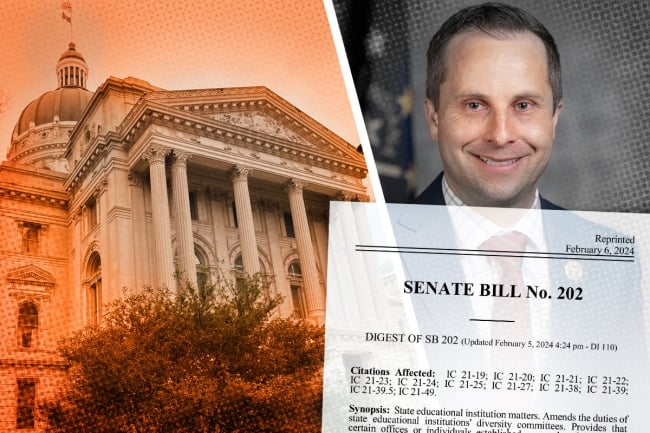

State senator Spencer Deery is the lead author of Indiana’s Senate Bill 202, which is now in the state House of Representatives.

In an echo of last year, state lawmakers in different parts of the country are pushing bills that would diminish tenure protections and target diversity, equity and inclusion programs.

Indiana’s Republican-dominated state Senate wants to do both at once. Earlier this month it passed a bill that takes aim at both tenure and DEI in public colleges and universities, tying them together with language that shifts focus from racial or other notions of diversity toward what it calls “intellectual diversity.” Senate Bill 202, now being debated in the majority-Republican state House of Representatives, defines that term as “multiple, divergent, and varied scholarly perspectives on an extensive range of public policy issues.”

The legislation would leave it to boards of trustees to determine what intellectual diversity means for individual faculty members’ disciplines, to gauge whether those faculty members have delivered it and to decide how much they should be punished if they fail to do so. Many of these trustees are appointed by the governor, currently Republican Eric Holcomb. Critics have said this means the bill would subject “hiring, tenure, and promotion”—and even employment after earning tenure—to “reviews that judge faculty based on political criteria.”

Senate Bill 202 says public institutions that have diversity offices or diversity-focused positions must include in their missions “programming that substantially promotes both cultural and intellectual diversity.” It also places the words “cultural and intellectual” before “diversity,” changing the role of university board of trustee committees that were supposed to review and make recommendations on faculty employment policies regarding diversity writ large.

The legislation would demand attention to “intellectual diversity” in promotion and tenure decision processes affecting faculty members, and it would mandate new post-tenure review policies—threatening academics’ careers and livelihoods if their teaching and scholarship don’t meet trustees’ criteria.

The bill’s lead author is state senator Spencer Deery, a Republican who served more than a decade as deputy chief of staff at Purdue University, including under former governor and Purdue president Mitch Daniels. In an interview with Inside Higher Ed, he framed the legislation as part of efforts to increase college attendance, noting there’s a perception that higher education discourages conservative views.

“We’ve got to find some way to change this perception,” Deery said. “Some of it might be perception, but I don’t think you can dismiss all of it.”

Indiana University’s president and state chapters of the American Association of University Professors have raised alarm about the bill.

“These measures would severely constrain academic freedom,” says a joint statement by the Purdue at West Lafayette and Indiana University at Bloomington chapters of the AAUP. “The security imparted by tenure is the fundamental protection of academic freedom; its loss would make university positions in Indiana undesirable. Recruiting and retaining top faculty, who will always have alternatives, will no longer be possible.”

Lea Bishop, an AAUP member, called the bill “a blank check to fire people based on identity or politics or for complaining about corruption, for complaining about discrimination.”

“It is nakedly about censoring speech, it is nakedly about punishing— This is not about touchy-feely things, about creating a more politically diverse environment,” said Bishop, who is a tenured law professor and dean’s fellow at Indiana University’s Robert H. McKinney School of Law, in Indianapolis.

“‘Intellectual diversity’ is antidiversity—that’s the point of the term,” Bishop said.

The bill says that the boards of the state’s public institutions—Indiana, Indiana State, Purdue, Ball State and Vincennes Universities, plus the University of Southern Indiana and Ivy Tech Community College—must pass policies to deny promotion and tenure to faculty members if “based on past performance or other determination by the board of trustees, the faculty member” commits one of three transgressions:

- Being “unlikely to foster a culture of free inquiry, free expression, and intellectual diversity”;

- Being “unlikely to expose students to scholarly works from a variety of political or ideological frameworks that may exist within and are applicable to” their discipline; or

- Being “likely,” when teaching or mentoring, “to subject students to political or ideological views and opinions that are unrelated to” the faculty member’s discipline or the course.

Indiana doesn’t currently have a statewide requirement for post-tenure review, according to the Indiana Commission for Higher Education. The bill would mandate that the institutions perform post-tenure reviews of faculty members at least every five years. Their boards would be required to determine whether these faculty members were continuing to meet the “intellectual diversity” and other criteria.

The bill would also require institutions to consider two further criteria in the post-tenure reviews: whether the faculty members “adequately performed academic duties and obligations” and if they “met any other criteria established by the board of trustees.”

That would mean a university’s board is “licensed to set any other criteria it wishes,” said Bob Eno, a member of the IU Bloomington AAUP chapter’s executive committee. Eno, a retired associate professor of East Asian languages and cultures, said the bill over all mandates “a system of surveillance and political scrutiny that is going to stifle the free flow of ideas.”

Failing to meet the new post-tenure review criteria could result in punishments including salary reductions, demotions and even firing, the bill says. And beyond post-tenure review, the bill would require considering the criteria when deciding whether to give bonuses or renew faculty members’ contracts—meaning it could impact nontenured faculty members, too.

Traditionally, faculty members are involved in evaluating and possibly disciplining their fellow faculty members. But the bill places that responsibility in the hands of the boards of trustees, with no mention of faculty involvement. Stephanie Masta, president of Purdue’s AAUP chapter and a tenured associate professor in the College of Education, said, “Our biggest concern about the bill is that matters of faculty governance, which includes review of promotion and tenure, are best held with the faculty.”

Deery said he envisions the boards delegating decisions to faculty members, though the bill does not say they must.

Asked about concerns that the bill would lead to politicized faculty reviews, Deery pointed to provisions that protect, among other things, “criticizing the institution’s leadership” or “engaging in any political activity conducted outside the faculty member’s teaching or mentoring duties.” But after an Inside Higher Ed reporter noted that the provision would appear to have no real effect due to how it was written, Deery said there had been “a drafting error.”

“You’re the first person to mention that to me, and we’ll fix it,” he said.

The legislation would also set up a process for students and employees to complain that faculty members aren’t meeting the criteria, mandate reporting of the complaints to the General Assembly and require universities to submit their DEI expenses alongside their legislative budget requests.

In a written statement, Indiana University president Pamela Whitten said, “While we are still analyzing the broad potential impacts of SB 202, we are deeply concerned about language regarding faculty tenure that would put academic freedom at risk, weaken the intellectual rigor essential to preparing students with critical thinking skills, and damage our ability to compete for the world-class faculty who are at the core of what makes IU an extraordinary research institution.”