You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

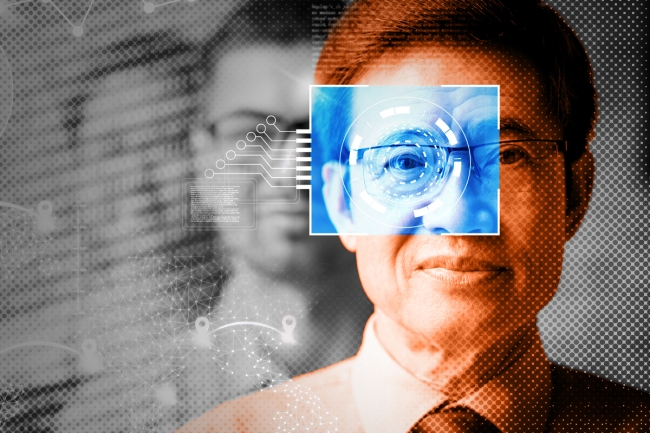

University presidents are turning toward artificial intelligence to help connect with students and cut down on cybersecurity concerns.

The friendly but authoritative voice of Astrid Tuminez delivers a cybersecurity PSA, narrating over an animated version of herself. Throughout the cartoon, the voice of the Utah Valley University president warns of perils such as phishing and phone scams before delivering a final, surprise reveal: the voice that sounded like Tuminez was that of an artificial intelligence–enabled bot.

“Trust that gut feeling that does not feel right,” the voice says. “And here’s a twist: you’ve been listening to an AI clone of President Tuminez’s voice.”

Then the real Tuminez appears, saying, “Just as my voice can be mimicked, so can others’; always be vigilant.”

Tuminez is not the first president to wade into the artificial intelligence waters. Wells College president Jonathan Gibralter used ChatGPT to write his commencement speech in June, and the University of Nevada at Las Vegas created an AI avatar of their president last year.

While there are broad possibilities of increasing student engagement and retention by leaning into AI, experts warn to keep watch for potential risks.

“They need to have careful considerations of ‘What is the purpose of this? What are the intended results?’” said Siwei Lyu, a professor of computer science and engineering at the University at Buffalo. “That’s part of the problem; we need to generally improve the awareness level of the general public of generative AI and what it can do.”

Behind the AI Scenes

UNLV was one of the first institutions to lean fully into AI bots, creating an avatar of President Keith Whitfield in March 2022. AI had not become a household term yet, but the university wanted to offer a unique way to connect students to the president.

“I really wanted to have a chance to speak to all students,” Whitfield said in a previous interview with Inside Higher Ed. “My staff, very wisely, said, ‘You’re a little crazy. You can’t do 31,000 students—let’s be realistic.’ I said, ‘There’s got to be a way.’”

The university spent seven months working with an external company to develop the digital president, which can address more than 1,000 questions from students, staff and faculty.

“It doesn’t look exactly like me, but you know it’s me,” Whitfield said. “But [students] say, ‘It sounds exactly like you.’ What’s amazing about that is they used both the things that they recorded me saying, and they can synthesize things to create answers to questions that hadn’t been asked before.”

Over the last year, the ability to make AI bots has advanced dramatically. At Utah Valley University, it took IT staffers just a month to mimic Tuminez’s voice.

“It’s actually quite easy—and that’s what’s so scary,” said Christina Baum, UVU’s CIO. “It’s pretty quick to clone a voice.”

The idea was pitched to Tuminez in September, after Baum saw an uptick in students falling for cyberscams, compromising their data despite increased cybersecurity measures with a two-factor authentication log-in.

“Students were giving up their credentials,” Baum said. “With the advent of more AI, we wanted to fight back and counter that. A member of the cyber team had an idea of ‘What if we did something with the president?’”

Tuminez was an executive at Microsoft for six years before taking the helm at UVU and, realizing the importance of cybersecurity awareness, she was “immediately” on board.

The video clip launched in late October and has more than 8,000 views.

“It’s kind of an arms race in cyber with bad actors,” Baum said. “This is prompting the right conversations for us, which is half the battle.”

While Tuminez acknowledges this exact move is not for all universities, she believes every university needs to get the conversation rolling on cybersecurity and the evolution of technology.

“This is both a very exciting and nerve-racking time,” she said. “All university leadership should understand what they’re about and have strategies and tactics to strengthen systems and educate your people. You’re only as strong as your weakest link.”

Opportunities and Obstacles

While some universities have leaned into AI, others are more cautious. The University at Buffalo’s Lyu was informally approached by university leaders in the summer about potentially using AI. They wanted to discuss creating personalized welcome videos for each of the incoming students—20,000 of them each year.

“I said technically, it’s feasible; practically, it may have some unintended consequences,” he said.

Lyu brought up the potential confusion or even anger that could ensue when incoming students learn it is not actually a university leader saying their name, but a bot.

“You think, ‘I got attention because university leaders are welcoming me by calling out my own name,’” he said. “But we have to disclose it’s generative AI—and then people would think about that and may think it’s contradictory.”

Harvard University also found itself in the headlines when its student computing science group created a deepfake of newly inducted president Claudine Gay. It was taken down the same day it launched, after it became known the deepfake of the university’s first Black woman president was given prompts to be “sassy” and “angry.”

Despite these issues, there are opportunities for using AI technology for student engagement on a case-by-case basis. Sharon Kerrick at the University of Louisville said there have been informal discussions of using it for admissions purposes, with the AI voice’s dialect changing to match where the prospective student is located—for example, if a prospect was viewing the admissions page from New York, the AI greeting would be in a New York accent.

While that project is in the discussion stages, Kerrick said it’s an example of the opportunities universities have and need to pursue—while keeping in mind the importance of a human element.

“We’ve seen chat bots work great to maximize and save time for students and ourselves, but then when you get a bit deeper, what’s the cross of human touch versus maximized efficiency?” said Kerrick, assistant vice president of Louisville’s Digital Transformation Center. “And how do we teach people of any age to continue to individually think and pilot things and try things?”

There’s also the possibility of speaking in other languages to prospective or current students.

“One thing with university presidents is they’re primarily appealing to U.S. audiences,” said V. S. Subrahmanian, head of Northwestern University’s Security and AI Lab. “It makes sense—if they want to address a primarily Hispanic population, it would be beneficial for them to be speaking Spanish.”

There is broad agreement on transparency, so if universities do intend to use AI, they need to disclose that they are using it, whether the approach is creating an avatar or using voice capabilities.

But many are holding off altogether.

“Five years ago if [university leaders] came to me to use AI, I would be excited,” Lyu said. “But as I’ve researched more, I’ve realized there’s a lot of unexpected—social, psychological—consequences that we need to consider. That’s what the problems are with deepfakes.”

Much like other technologies, there needs to be an inherent understanding before diving in, according to Subrahmanian. But, he said, now that the technology is widespread, it’s up to the universities to teach their students about identifying the potential AI use.

“Parents teach their kids the usage of the internet, saying, ‘Stranger danger.’ That’s an essential hygiene we teach our kids today, and this has to be part of that,” he said. “[With AI], it’s not one cat out of the bag; it’s a zillion out of the bag, and putting the pack of cats back in the bag is basically impossible.”