You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

E-textbooks are more popular than ever, despite faculty’s distrust of them.

anyaberkut/iStock/Getty Images Plus

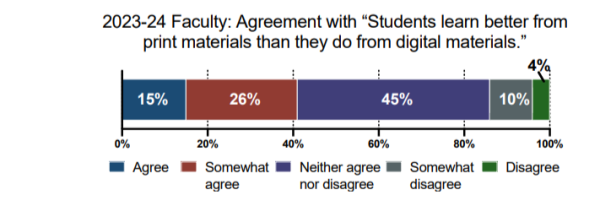

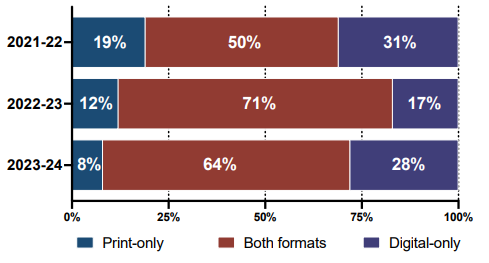

Fewer than 10 percent of college courses now solely require physical textbooks, down from 20 percent two years ago. But professors still believe paper books are more effective than their digital counterparts.

That’s according to a report released today by Bay View Analytics, which conducts an annual survey looking at the use of educational resources and digital tools by faculty members. Bay View found that while a majority of faculty members (81 percent) believe digital textbooks allow students more flexibility, nearly half (41 percent) think physical textbooks are better for learning.

Faculty believe students learn better with physical versus digital textbooks, despite a recent shift toward mostly digital materials.

Bay View Analytics

Julia Seaman, director of research at Bay View Analytics, said “outward forces” are driving professors to change, whether or not they want to. “They do, as a whole, have slightly more traditional preferences, but we see them act against those preferences,” Seaman said. “Institutions are pushing digital adoption; it’s one way to promote themselves, like they’re a modern campus. And [ebooks are] consistently cheaper, and with the rise and use of online and blended courses, it’s easier to use digital or online materials.”

The report, which has been conducted since 2009, polled roughly 3,400 faculty members in higher education institutions across all 50 states in April. Over the years, there has been a continued digital push—both in the materials used and in course modalities—and this year’s findings show that despite their misgivings about those digital offerings, faculty will continue down that path, which accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Seaman expects the 8 percent of courses that only assign a physical textbook, for instance, to dip to 2 to 5 percent in the coming year.

A decreasing number of courses are requiring physical textbooks, instead shifting toward offering digital options as well.

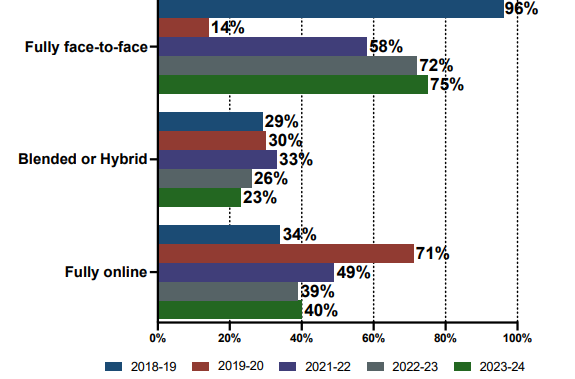

More professors than ever are now teaching multiple types of classes—in person, online-facing or a mix—with more than a quarter teaching two or more course modalities and another 8 percent teaching three or more. Sixty-six percent of faculty members taught a single modality in academic year 2023–24, down from 72 percent the previous year. Professors who taught two or more modalities typically taught in-person and online-facing courses, with the fewest teaching a hybrid course that mixes both in-person and online components. Just 17 percent of faculty combined hybrid and fully face-to-face courses, and 14 percent combined hybrid and fully online courses.

The number of faculty members who taught face-to-face, hybrid or online-only courses stayed roughly the same compared to the prior year, after soaring during the pandemic. Julia Seaman and Jeff Seaman, who’s the director of Bay View, believe the leveling off could be indicative of a new status quo—for the time being, that is.

Teaching modalities have stayed relatively stagnant over the last two years, suggesting a steadying in the post-COVID era.

Bay View Analytics

“We’ve been speculating at some point the growth level was unsustainable,” Jeff Seaman said, adding that the adoption and awareness of digital tools was not “led by some small subgroup; it’s pretty pervasive.”

But while the COVID-driven changes have leveled off, he said there are other factors that could drive further digital adoption, including a looming enrollment cliff, the rise of artificial intelligence and the public’s declining confidence in higher education writ large.

“Our conclusion isn’t that we’re at the end of the line,” he said. “We’ve reached a plateau for the forces that have been, up until now, but those are changing.”

Adoption and Usage of OER

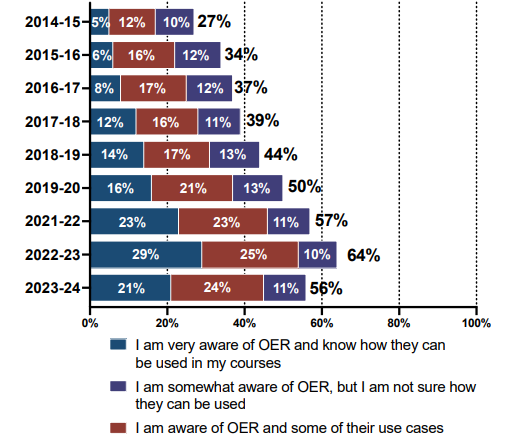

The continued shift toward online course modalities may also be impacting faculty members’ adoption, awareness and perception of open educational resources, otherwise known as OER. These are course materials that are published digitally, usually in a free or low-cost model, and available through an open license. Despite the lower cost and easier access, many academics do not know about OER.

For the first time since Bay View started this study in 2009, there has been a drop in both OER use and awareness, which hovers at 56 percent for those who are “aware” or “somewhat aware” of OER materials, down from 64 percent in the 2022–23 academic year and in line with similar numbers from the 2021–22 academic year.

Faculty awareness and use of open educational resources have dropped for the first time since the report began.

Bay View Analytics

“We definitely didn’t expect this drop; we more expected it to even out like the other trends,” Julia Seaman said, adding she does not know of a specific driving force behind the decline. “We can’t tell you if this is a reversal, if this is where OER [awareness] should land or if it’s a one-off trend.”

Awareness of copyright, public domain and Creative Commons licensing also all dropped from the prior year, with 80 percent “aware” or “very aware” of copyright, followed by 68 percent for public domain and 53 percent for Creative Commons licensing.

Jeff Seaman said that dip—like the lower awareness of OER—may be a result of the continuous push toward digital textbooks.

“Previously, everything went through the bookstore, but that has changed, so what faculty are paying attention to has changed,” he said. “It’s just no longer on their radar as it was before, and with OER, if it’s bundled into tuition or licensing fees or course fees, there’s a lot of changes for faculty members that take away them from needing to pay attention to cost of material or the naming of it.”

Forty-one percent of professors reported using OER in some form in the most recent academic year—for textbooks, in some cases, and for homework and interactive activities in others. Roughly one-quarter (26 percent) of faculty members reported requiring the use of some OER materials in their courses, down from 29 percent the prior year, but up slightly from 2021–22, when 22 percent of faculty said they required OER materials. Unsurprisingly, professors who taught hybrid or online-only courses reported using OER more than their counterparts who taught only in-person courses.

The Seamans believe that as the higher education market continues to change, faculty members will—begrudgingly or not—continue to adapt as well.

“Years of AI and tech replacements of faculty roles have left them defensive, but if you talk to a lot of faculty in general they do seem a lot more open to digital course materials,” Julia Seaman said. “The big acknowledgment is that these tools are required for postsecondary or workplace success; they know that’s the world students will be entering.”