You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Panelists at the annual Educause conference tackled multiple ed-tech topics but largely focused on AI.

David Ho/Inside Higher Ed

As Susan Grajek wrapped up presenting Educause’s top 10 strategic trends for 2024—a list topped by cybersecurity, data quality and the enrollment crisis—she paused.

“Isn’t something missing?” she asked the packed ballroom with a knowing laugh. “Something big that popped around 11 months ago that’s taking a lot of everyone’s attention. Generative AI?”

While artificial intelligence landed at No. 13 on the “top tech trends” list, Grajek, Educause’s vice president of partnerships, communities and research, acknowledged that the technology is so pervasive that Educause made AI an “honorary topic” for the top 10 list.

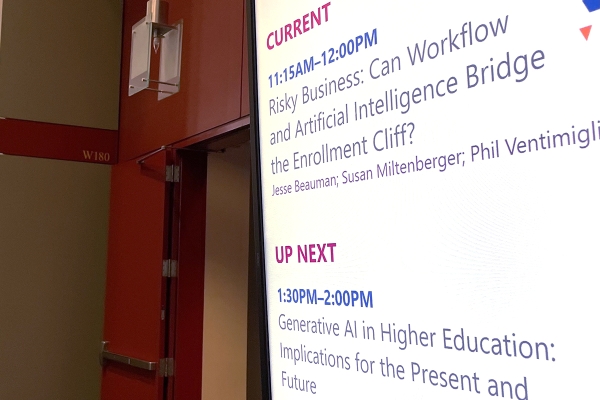

AI was anything but honorary in Chicago this week at Educause, the annual education conference aimed at technology leaders. AI has dominated many technology conversations since the public debut of OpenAI’s ChatGPT in November 2022.

“I don’t know if I’ve seen a topic dominate the way AI has this year,” said Ryan Lufkin, VP of global strategy at Instructure. He’s attended the Educause conference for more than two decades.

About one out of eight noncorporate, regular sessions were focused on AI over the four-day conference—or 16 out of 128, according to a rough count by Inside Higher Ed. Many of the sessions ran concurrently across the sprawling McCormick Place convention center.

Beyond the panels, keynotes and posters dedicated to AI, many other sessions on varied topics couldn’t help but mention the technology.

In comparison, last year the conference had zero sessions focused solely on AI technology and only three to four poster presentations.

This year’s AI conversations largely come to the same conclusion: there’s a cautious optimism around the technology. That was also seen in Inside Higher Ed’s annual survey of chief technology officers, with more than one-third of respondents stating they are considering experimenting with artificial intelligence.

Expertise Not Needed

Heath Price, an associate vice president at the University of Kentucky, spoke at a panel entitled “Beyond Chatbots: Simplifying Visibility With AI to Transform the University Experience.” He noted the many Educause sessions this year that had “AI” in the name and said higher ed attendees might be feeling lost, left behind and struggling to catch up to the artificial intelligence frenzy. He sought to reassure his audience they are not alone.

“We don’t know what we’re doing yet,” he said. “We’re experimenting, exploring how we can think about different tools.”

Price’s co-panelist, Purdue University CTO Mark Sonstein, agreed, saying that these are very early days for AI, with efforts just beginning.

Annie Chechitelli, chief product officer at Turnitin, said she believes it is important to have conversations about AI, even if the actions taken differ by institution.

“What’s different with this is some institutions say they’re not ready for it, but it needs to be an ongoing conversation,” she said. “Just try it; if every educator just tried it themselves, the conversation would become much richer.”

Brian Basgen, CIO at Emerson College, agreed, saying it’s important to continuously play with the AI tools.

“Try it every day, at least once a day,” he said. “Throw at it some sort of real problem you’re trying to solve. Really importantly, do not take the first response. It is at best a rough draft. Keep interacting with it two, three, four times; see where it takes you. That’s troubleshooting the model, giving it more context. It’s going to make you better at prompting it, and as a technologist, it’s going to help you understand how it’s working.”

AI sessions dominated Educause's annual ed-tech focused conference, held in Chicago from Oct. 9-12.

David Ho/Inside Higher Ed

Daniel Skendzel, executive director of teaching and learning at the University of Notre Dame, presented on his institution’s academic innovation hub. While he acknowledges not every institution has the funding to back universitywide initiatives, it is important that every institution get into the AI space and work across silos.

“We’re going through that emerging tech period of trying to understand and leverage it ethically and most impactfully,” he said. “And it’s going to take time, but absolutely this is a game changer and we can’t hide from it. Well, we would be foolish to hide from it.”

Cautions and Concerns

Along with the excitement of the emerging technology comes concerns, including worries about biased decision-making, reduced critical thinking and worsening misinformation, deepfakes and cyberattacks.

Kate Miffitt, director for Innovation at California State University’s Office of the Chancellor, addressed some of the anxieties at the session “Boom or Bust? The Future of Generative AI in Higher Education.”

“The academic integrity issues were sort of what spurred all of the attention initially in higher ed for ChatGPT, but I think those of us in IT were a little bit more mindful of how it could be used for cyberattacks,” she said. She added that AI could make things worse for existing challenges around cybersecurity and misinformation.

On the same panel, Josh Weiss, director of digital learning solutions at Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education, said, “AI literacy is going to be paramount, especially for our young learners.” He said he thinks about it with his young daughter in mind.

“What are the enduring questions she should be asking herself?” Weiss said. “Is it OK to work alongside an AI for this type of task versus this type of task? Is it taking away from future opportunities or future skills she might have? I think students do have the capacity to reflect, but I’m not sure right now we’re giving them the right questions.”

There’s also concern with working with companies that latch on to the latest buzzword and sell “AI products” not really powered by the technology.

“Watch out for the hype,” Grajek of Educause said. “There’s money to be made on AI. And providers and consultants may be proud of overselling their AI-driven products and services.”

AI Already in Use at Some Institutions

Sonstein, the Purdue University CTO, said his team currently has a generative AI system that can give advice related to technical documentation, like how to set up a networked printer. Next month, he said, an AI will learn from the university’s public website and be able to answer questions about which dining facility has things like pizza and how to find buildings on campus.

“The ultimate goal is for a student to be able to say [to an AI], ‘You know my plan of study for my degree field. You have access to all of the classes I take and all the prerequisite classes I need. Build me a schedule for next semester. And, oh, I don’t like to get up before 10 a.m. and I don’t want any classes on Thursdays,’” Sonstein said. “And have it automatically generate your schedule … and sign you up for those classes.”

Beth Ritter-Guth, associate dean for online learning and educational technology at Northampton Community College, said she preferred to envision AI as a “co-pilot” for learners and employees.

She described how she had encouraged students to use ChatGPT in her 400-level English course on women authors. She has an assignment designed to train the students to use the technology, then try to “find the information that was used to train the AI” and “to “look and see what information is out there” about early women authors like Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe.

When it comes to setting policy, she suggested clarity is key. She said faculty members are “panicked” about whether administrators will support them when there is an AI problem.

Her advice: “Be clear in your syllabus, and in your assignments. If you are clear in your expectations, we will support you.”