Free Download

Given the environment surrounding higher education and the workforce, it seems like this should be transfer's moment.

Transferring from one college to another has historically been harder than it should be, with impediments at many points along the way. The incentives for institutions and students to smooth out the process right now are greater than ever before, given the current and pending declines in traditional college-age students, the likelihood that COVID-19 will scramble students' college-going patterns, and the societal push for racial equity that is increasing pressure on colleges to diversify their student bodies.

A new survey from Inside Higher Ed, however, underscores some of the attitudes and practices that have historically impeded the path for transfer students -- and identifies perceptual gaps between administrators at two-year and four-year colleges that could be difficult to overcome.

Among the key findings of "The Transfer Landscape: A Survey of College Officials," which queried administrators who are involved with transfer policies or practices at two- or four-year colleges:

- Roughly three-quarters of administrators at two-year and four-year colleges alike agree that students who transfer from one institution to another perform as well as or better at the receiving institution than do students who began at that institution.

About the Survey

"The Transfer Landscape: A Survey of College Officials" is available, free, for download here.

The survey of 143 campus administrators was conducted by Hanover Research on behalf of Inside Higher Ed.

Inside Higher Ed’s editors will lead a webcast discussion of the survey’s results on Thursday, Nov. 19, at 2 p.m. Eastern. Please sign up here.

The survey was made possible by advertising support from Huron.

- Officials at public and private four-year colleges are far likelier than their peers at community colleges to say that four-year institutions are effective in working with students to approve academic credits that apply to a major, advising them on their academic options and giving them sufficient academic support.

- Similarly, two-year college officials give themselves higher ratings at preparing students for transfer than do their four-year-college counterparts -- but even the community college officials don't rate themselves very highly.

- Two-thirds of administrators at private four-year colleges and 44 percent of those at public four-year universities say it takes their institutions less than two weeks to tell transfer students how many of their academic credits will be approved. In contrast, 60 percent of community college officials say it takes transfer students at least two weeks to get credit approval, and one in five say it takes at least a month.

- Officials from all institutions overwhelmingly agree that a "centralized approach to credit evaluation works better for transfer student enrollment" than does leaving those decisions up to individual departments and professors. But four-year college administrators are two to three times likelier than their two-year-college peers to agree that "faculty experts in individual academic departments are effective at deciding which and how many credits students may transfer to a major program."

Taken together, the findings reveal that despite growing interest in recruiting transfer students (especially among private four-year colleges), two-year and four-year college administrators often focus more on "pointing the finger at the other side for not adequately preparing or supporting transfer students" rather than taking "collective responsibility for transfer students from community college start to university finish," says John Fink, senior research associate at the Community College Research Center at Teachers College of Columbia University.

Barriers to Transfer

Transferring from one college to another -- particularly from a two-year to a four-year institution -- is harder than it should be. While 80 percent of students who start out at a community college say they intend to earn a bachelor's degree, fewer than a third of them transfer to a four-year college within six years, and just one in six earns a four-year degree within that time.

And more than four in 10 students who seek to transfer academic credits from one college lose a meaningful proportion of those credits, and 15 percent are unable to transfer any credits at all, according to the Community College Research Center. Fink attributes the "leaky transfer pipeline" to a mix of academic, financial and cultural factors, which have a particularly damaging impact on Black, Hispanic and low-income students.

Inside Higher Ed's new survey was designed to help gauge the current state of two- and four-year colleges' policies and practices and the attitudes of administrators who work closely with transfer students. The survey went to administrators at two-year and four-year public and private colleges who play a role in their institutions' policies and practices related to student transfer. (Note: The response rate was low -- perhaps because it was conducted in September and October, as college administrators were preparing for an unprecedented fall. So while Inside Higher Ed and Hanover Research have confidence that the results are directionally accurate, they should be interpreted with caution.)

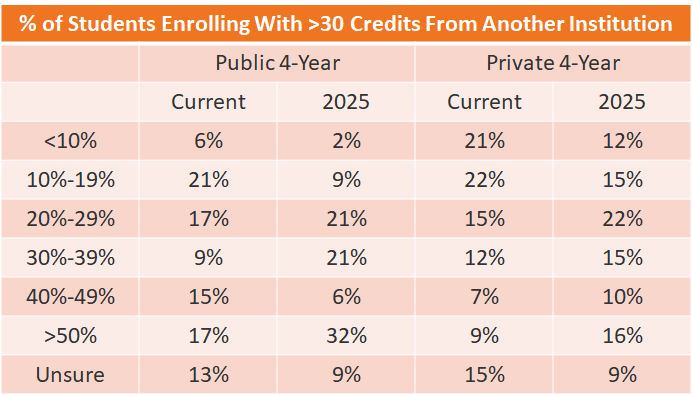

To get the lay of the land, the survey asked officials at the four-year colleges what proportion of their students had accumulated at least 30 credits at another institution before enrolling. The most common answer, by slightly more than one in five at both public and private institutions, was between 10 and 19 percent of students. The next largest category for private institutions (21 percent) was less than 10 percent of students, while 17 percent of officials at public four-year universities each said that between 20 and 29 percent of their students and more than half of their students had accumulated at least 30 credits elsewhere.

Experts have widely speculated that COVID-19 will disrupt students' educational plans in ways that lead more of them to enroll at multiple colleges and universities, and respondents to the survey seem to expect that as well. When asked what proportion of their students in 2025 they expect will enroll with more than 30 academic credits from elsewhere, they anticipated sharp increases, as seen in the table below.

While more than two in five private college transfer administrators say that less than 20 percent of their current students enroll with at least 30 credits, roughly that same proportion of officials expect their students to have at least 30 percent five years from now.

Community college transfer administrators also expect to see more student mobility over the next five years.

Asked what proportion of their students transferred to a four-year institution between the 2018-19 and 2019-20 academic years, 30 percent said between 30 and 39 percent and 26 percent said between 10 and 19 percent. Thirteen percent said that at least half had transferred.

Looking ahead, 13 percent of the community college officials continue to expect to have more than half their students transfer to a four-year college. But 17 percent expect from 40 to 49 percent of their students to transfer, up from 4 percent now, 26 percent expect from 30 to 39 percent to transfer, and 22 percent expect 20 to 29 percent to transfer, up from 13 percent now.

Taken together, those data establish that most colleges -- whether they tend to send students on to transfer or to receive them -- expect COVID-19 to scramble the enrollment picture and accelerate the movement of students between institutions. That makes getting the transfer process right all the more important.

Managing the Transfer Process

Most of the rest of the survey focuses on assessing how well (or not) colleges are handling student transfer now. And the answer isn't particularly heartening.

Transfer administrators at four-year colleges and two-year colleges generally agree that four-year institutions do a pretty good job at recruiting potential transfer students to apply and persuading them to enroll.

But on many other aspects of the transfer process, four-year college officials have a much rosier view of their effectiveness than do their community college counterparts.

For instance, more than half of transfer officials at both private (61 percent) and public (51 percent) four-year colleges say their institutions are extremely or very effective at working with transfer students to approve academic credits that apply toward a major, and roughly half say the same about how effectively they provide academic support to transfer students who enroll. And pluralities say they are extremely or very effective at advising prospective transfers students on their academic options.

Few community college officials -- 13 percent, 4 percent and 9 percent on those three questions, respectively -- agree.

There is somewhat more consensus on whether four-year institutions provide sufficient social integration services to transfer students who enroll -- but the agreement is that they don't. Far more officials at public four-year colleges (47 percent) and private colleges (30 percent) say their institutions are slightly or not at all effective at helping transfer students integrate into their student bodies than say they are extremely or very effective (15 percent and 19 percent, respectively).

Two-thirds of community college transfer administrators say the four-year colleges are ineffective in this area.

The same basic pattern holds when officials from both sectors rate the performance of community colleges. Four-year and two-year college officials alike say community colleges are effective at encouraging students to transfer and, to a lesser extent, providing academic support to those students who plan to enroll at a four-year institution.

But four-year college administrators, public and private alike, are more likely to rate two-year colleges negatively than positively on working with four-year institutions to approve academic credits toward a major and advising prospective transfers on issues they may face after transferring. Community college administrators rate their own institutions more highly, but even they acknowledge some of their colleges' shortcomings.

Experts on the transfer process found it unsurprising -- but still distressing -- that four-year and two-year college officials alike tended to focus on perceived flaws of the other.

"There is lots of finger pointing, finding that things aren’t working at the other institution," says Janet Marling, executive director of the National Institute for the Study of Transfer Students at the University of North Georgia. "There are some perceptions, and misperceptions, and they do divide institutions in their willingness to come together on behalf of students."

The Contested Credit-Approval Process

The divided perspectives are evident in questions about arguably the most central part of the transfer process: the approval of a student's previous academic credits toward a major. Students who accumulate significant numbers of credits at one institution only to see many of them rejected by the receiving institution -- and even more of them failing to apply toward a major -- waste time and money that can disrupt if not deter their educational plans.

Two-thirds of four-year private college administrators (68 percent) and 44 percent of public college officials say transfer students receive credit approval from their institutions in less than two weeks. Just 22 percent of two-year college officials agree.

Instead, four in 10 of them say that approval takes between two weeks and a month, and one in five say it takes more than a month.

Juana H. Sánchez, senior associate on the postsecondary education team at HCM Strategists, a public policy consulting firm, said that divide likely results from two-year and four-year officials having different impressions of when the process starts.

"When I was an adviser at a four-year university, my awareness of the student came when they were sitting in my office after being admitted," says Sánchez. "Whereas if I'm the adviser at a two-year college I'm trying to expose students to transfer early on, and trying to give them a sense of credit applicability early on."

"It's one of the fundamental disconnects in this whole process," she adds. "Professionals who are supporting students at the four-year institutions may have a shorter-term view than faculty mentors and others at community colleges do, and that colors how they view what happens to students."

The credit-approval process is controversial terrain. At many institutions, decisions about which of a student's incoming credits will be awarded and (especially) which will apply toward a major or degree program are left to individual departments and faculty members within them. Those who favor this approach believe that faculty experts are best positioned to make those calls. Many advocates for students argue that this individualized approach injects enormous subjectivity and uncertainty into the process; they tend to favor a more centralized approach that is shaped by faculty members but streamlined into one office or decision-making process.

Respondents to the survey, regardless of sector, overwhelmingly agreed that "a more centralized approach to credit evaluation works better for transfer student enrollment." (Administrators at four-year private colleges were more inclined than their peers to "strongly" agree.)

Here's the rub: four-year and two-year college officials differed widely on the related question of whether "faculty experts in individual academic departments are effective at deciding which and how many credits students may transfer to a major program." More than two-thirds of public university administrators and more than half of private college officials agreed, compared to just 20 percent of community college transfer officials.

To Alison Kadlec, founding partner at Sova Solutions and a former political science professor at several four-year colleges, the agreement on the first question "suggests a certain kind of progress," in terms of college administrators recognizing that students need more clarity, as early as possible, about whether and how their credits will transfer.

But the disagreement about how effective four-year college faculty members are in making those decisions reveals "a values-based problem that needs working through," Kadlec says. "There's an increasingly apparent tension between academic freedom and the interests of students, particularly disadvantaged ones. Faculty members see themselves as the guardians of 'quality,' and to them that's an important value. But there can be a tension between that and a commitment to racial [justice] and equity that we need to address."

Fink of the Community College Research Center agrees. "Centralized approaches to credit evaluation … can enable automation and better transparency in these otherwise lengthy, confusing processes. Generally this is a win-win for colleges as it streamlines administrative processes, provides clarity for prospective transfer students and advisers, and speeds up credit evaluations so students can make enrollment decisions knowing how many credits will actually transfer."

Adds Troy Holaday, president of College Source, which works with colleges on transfer-of-credit issues, "The need for a centralized, transparent and automated approach to credit evaluation for all U.S. institutions cannot be overstated. We have to better inform students as to their options for successful credit transfer and plug the leaks in the system that result in unnecessary loss of credit, which in turn wastes student resources and increases time to graduation."

Transfer Students' Performance

On balance, campus administrators, regardless of sector, believe transfer students perform well. Officials at two- and four-year colleges alike say that roughly three-quarters of students who transfer into an institution perform at least as well as students who began their academic careers at that institution. Four-year college administrators say that roughly a quarter of transfer students perform better than their native students, while about half perform as well.

Only about one in 10 transfer students performs worse than the typical native student, four-year administrators say.

Fink of CCRC said he found it "encouraging against a backdrop of community college stigmatization and the myth on some university campuses that transfer students are not strong academically." He said the respondents' perceptions are in line with empirical evidence finding that transfer students to do as well or better academically than "matched peers," even at the most selective four-year institutions.

But college administrators' positive view of the academic performance of transfer students makes it particularly confounding that four-year colleges so often reject transfer students' incoming academic credits, says Sánchez of HCM Strategists.

"Why is it when we approach conversations about credit applicability, we start with the assumption that the courses students have taken, the learning they have, is somehow inferior?" she says. "Yet, when we see how they’re performing, we don’t see that gap in readiness. Why are we hesitant to talk about things like credit by examination and prior learning that are going to accelerate their time to degree?"

Concerns, Policies and Practices

The survey closed with a set of questions about administrators' concerns about transfer students and the policies and practices institutions have in place -- or don't -- to improve the transfer process.

On balance, two-year college officials are more concerned about how transfer students fare at four-year institutions than are four-year college administrators.

Fully three-quarters of community college administrators say they are concerned about transfer students' inability to afford tuition, which is also the top concern expressed by officials at private four-year colleges (56 percent).

Respondents from two-year colleges are about twice as likely as officials from four-year colleges to worry about how the "difficult credit transfer process" will affect students (60 percent versus 29 and 36 percent for private and public four-year college administrators, respectively). They are also significantly likelier to express concern about how many of students' credits will be applicable toward a major and the students' ability to find support services and to enroll in the necessary classes.

Given a list of policies and practices that their institutions either had in place pre-COVID or had implemented since the pandemic began, respondents from four-year colleges seemed much more focused on recruiting more transfer students than on efforts to ensure their success upon transferring.

More than two-thirds, for instance, said they had initiatives to increase recruitment of transfer students, while fewer than half said they had expanded faculty advising or social integration programs for transfer students. Fewer than one in five said their institutions had eased restrictions on credit transfer policies toward major requirements or "catch-up" programs for students who had significant numbers of credits that did not transfer to the four-year institution.

Sánchez of HCM said it was unsurprising that four-year colleges were seeking more transfer students, given the realities of the postsecondary enrollment picture in which the number of graduating high school students is expected to flatten or decline in the coming years.

But colleges would be wise, she said, to focus as much or more on retaining transfer students and ensuring that their institutions are hospitable environments for those students.

"You can't just look at how many students are we getting in the door," she says. "How can we get four-year institutions to think more about investment that will help students succeed once they’re admitted?"