Free Download

At first glance, the overall responses of 746 campus chief executives to Inside Higher Ed’s new Survey of College and University Presidents may seem discordantly upbeat, particularly on financial questions.

Presidents, whose responses were solicited early this year before the onset of the coronavirus became apparent, seem solidly confident in the financial stability of their campuses, with a record-high 69 percent of all college leaders agreeing that their institution will be financially stable over five years, up from 66 percent last year, and 57 percent saying the same over a 10-year period, the same as in 2019.

Most presidents also largely play down the possibility that their institutions could merge or close, with the vast majority (84 percent) saying they’ve not seriously discussed mergers with their senior campus colleagues and 85 percent saying they don't believe their college should merge with another within five years.

More on the Survey

Inside Higher Ed's 2020 Survey of College and University Presidents was conducted by Gallup. A copy of the report can be downloaded here.

Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

On Thursday, April 16, Inside Higher Ed will present a free webcast to discuss the results of the survey. Please register here.

The Inside Higher Ed Survey of College and University Presidents was made possible in part with support from Everfi, EY Parthenon, Gallup, Canvas by Instructure, the Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi and Wiley Education Services.

But a closer look at the data tells a somewhat different story -- that of a widening divide between the haves and the have-nots, and a hollowing out of the middle.

Yes, 57 percent of presidents express confidence in their college’s financial stability over a decade. But while 64 percent of public doctoral university leaders and 59 percent of private college presidents answer that way, just 46 percent of public master’s and baccalaureate college chief executives do. Geographically, 64 percent of presidents in the South and 58 percent in the West are confident in their 10-year outlook, compared to 54 percent in the Northeast and just 48 percent in the Midwest.

By a margin of 23 percent to 9 percent, presidents at private colleges and universities are more likely than their public college peers to say they’ve had serious internal discussions about merging with another college.

Presidents in the Northeast (19 percent) and Midwest (18 percent) are much likelier than their colleagues in the South and West (12 and 10 percent, respectively) to think their institutions should merge with another. And leaders who said they'd had internal discussions about merging were almost 10 times likelier than presidents who said they hadn’t (59 percent to 7 percent) to believe their college should merge.

Those findings suggest a picture of a large group of college leaders who believe their institutions are positioned well for the future -- and a smaller set who very much do not. It’s hard to know, of course, if all of those who seem confident are justified in feeling that way; experts interviewed for this article disagree on that.

Among other topics explored in the new study, Inside Higher Ed’s 10th annual survey of college leaders, which was conducted by Gallup and released today:

- Presidents’ assessments of the state of race relations on college campuses nationally and on their own hit their lowest points since Inside Higher Ed began asking questions on this topic in 2014. Just 19 percent of those surveyed described race relations on college campuses nationally as either excellent (1 percent) or good; 77 percent said race relations on their own campus were excellent (14 percent) or good (63 percent).

- College leaders overwhelmingly oppose Democratic proposals to make public higher education free and to cancel much if not all student debt, with 22 percent of all presidents supporting those plans. Only a third of public college presidents support free public college, although community college presidents are much likelier than others to do so.

- Presidents are more likely to view the Trump administration’s increased scrutiny of foreign scholars as unreasonable than reasonable, although presidents of public doctoral universities -- where most of the scrutiny is focused -- are evenly divided. A slight majority (52 percent) thinks the policies result in racial profiling of Chinese faculty members and graduate students.

- More presidents support (40 percent) than oppose (31 percent) the federal government’s recent publication of program-level data on students’ debt and postcollege income and favor the idea that state and federal regulators should “publish information about the financial sustainability of colleges.” A caveat, though: a majority of public college presidents support that idea, while barely two in 10 leaders of private colleges do.

Rising Confidence -- for Most

Inside Higher Ed has surveyed presidents for a decade, but it has asked campus leaders only since 2014 to judge the financial stability of their institutions over five and 10 years. As seen in the chart below, except for a dip in the second of those seven years, their overall confidence has risen steadily.

That rising confidence has perplexed some experts on higher education finance, given the readily apparent pressures that are building on institutions in the form of constrained state funding, flat or falling enrollments for many institutions, and a demographic “cliff” that seems destined to reduce the number of traditional-age college students in the next decade.

But the numbers, examined more granularly, reinforce what has seemed increasingly clear in recent years: that while many if not most colleges will be “fine” in the coming years, there is a set of institutions -- be it a tenth, a quarter or more -- that faces serious, if not existential, financial challenges. The survey suggests that even leaders of those institutions seem to be acknowledging that (in this private polling, at least, if not publicly).

Sector differences present the first evidence of a disappearing middle.

Asked to respond to the statement “I am confident my institution will be financially stable over the next 10 years,” nearly two-thirds of presidents of public doctoral universities strongly agree (23 percent) or agree (41 percent), and just 6 percent disagree.

For private doctoral/master’s institutions, 59 percent of leaders of agree (21 percent strongly), up sharply from 2019, when only 50 percent did so. Fourteen percent of private doctoral/master’s university presidents disagreed, double the 7 percent who did so last year.

In the 2019 survey, 43 percent of leaders of these institutions chose the middle option on the five-point strongly disagree to strongly agree scale -- essentially neutral or “not sure.” In this year’s survey, that figure was down to 26 percent, with 9 percent more presidents agreeing and 7 percent more disagreeing.

The picture looks a little different for private baccalaureate colleges and public master’s/baccalaureate universities, widely viewed as the most vulnerable of postsecondary institutions. Fewer leaders of private four-year colleges expressed confidence in their 10-year outlooks this year (59 percent) than last year (64 percent), but fewer also expressed the opposite (6 percent versus 12 percent).

And for regional public colleges, 46 percent agreed that their institutions would be financially stable over 10 years, down from 50 percent in 2019; 13 percent disagreed, down from 18 percent.

Jessica Wood, a senior director and education sector lead at S&P Global Ratings, one of the major bond ratings agencies, said the large proportion of presidents who seemed confident in their financial futures to be "surprisingly optimistic." While many institutions may feel in a strong financial position "coming off a few years of strong market returns and endowment growth, as well as low interest rates," they "have also been investing in their campuses and programs – and so operating margins have been less robust recently than historically, even for stronger institutions."

She added: "Given potential for an economic slowdown and the exacerbation of COVID, along with the troubles facing the sector, our view is less optimistic."

Questions about mergers and consolidations revealed more gaps in perceptions between stronger and weaker institutions.

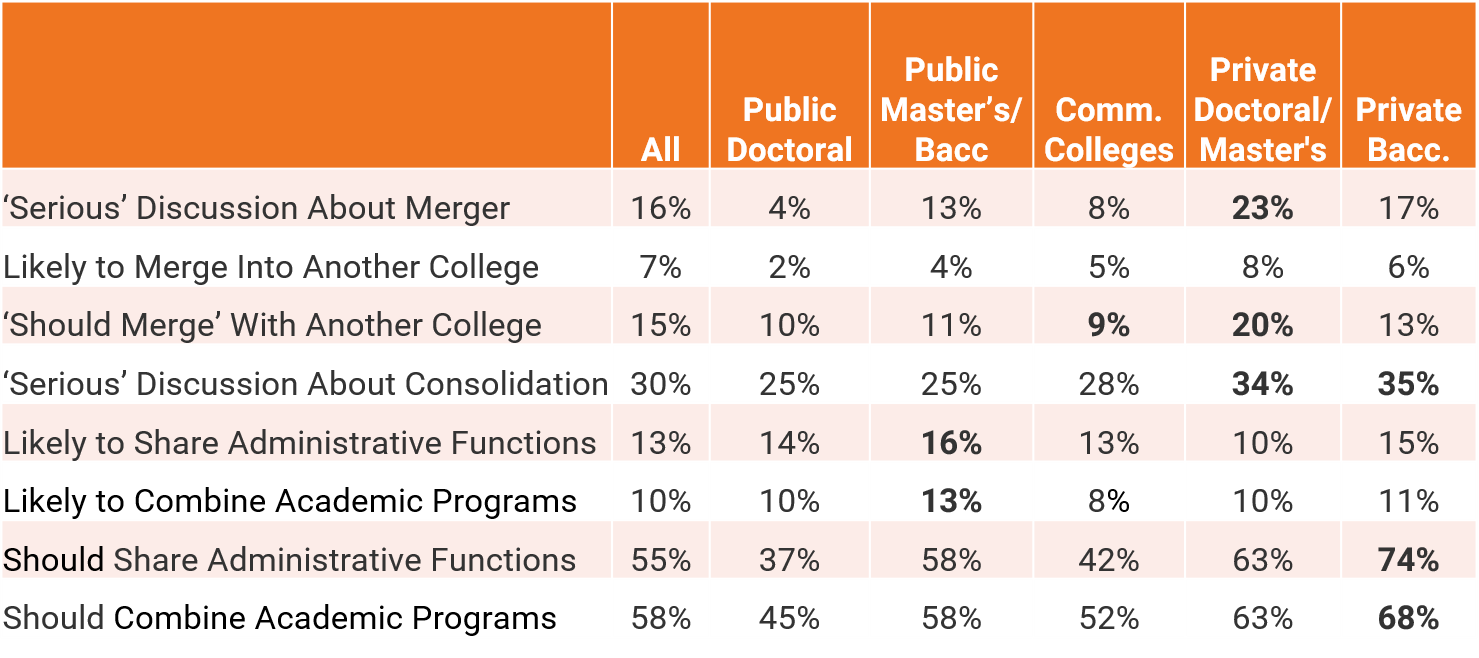

This is the first year that Inside Higher Ed asked presidents whether they’d had “serious internal discussions” about mergers; about one in six (16 percent) said yes. Leaders of four-year doctoral universities and community colleges were far less likely to have done so (4 percent and 8 percent, respectively), compared to 23 percent of private doctoral and master’s institutions.

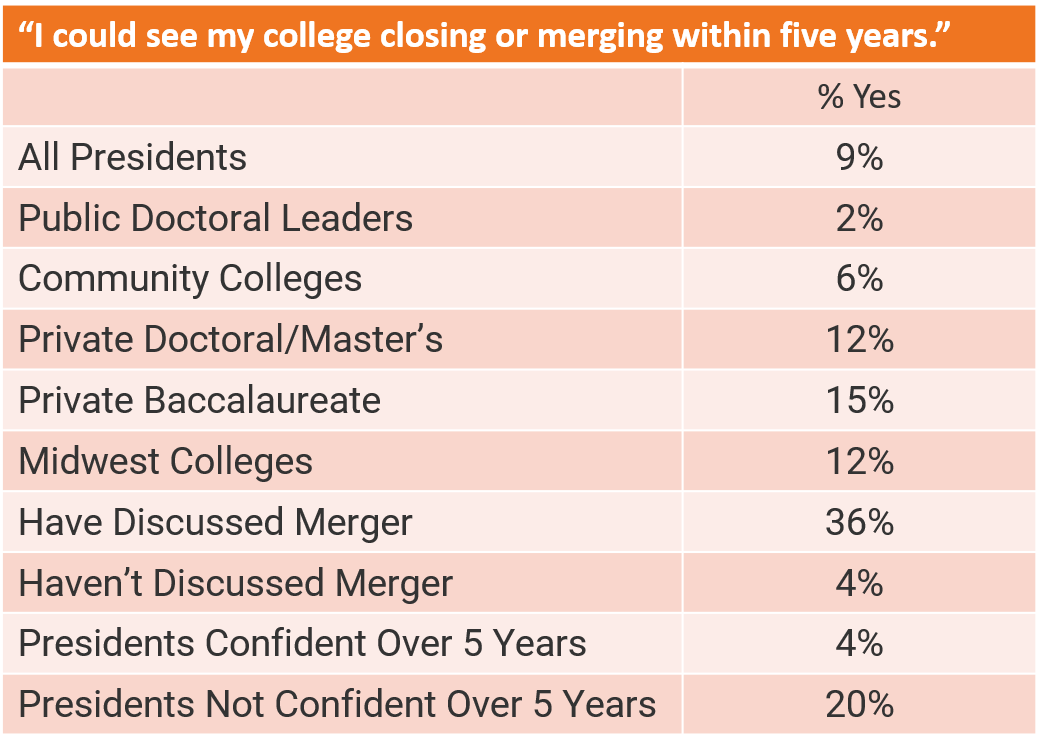

Another question asked presidents to respond to the statement “I could see my college closing or merging within five years,” and the answers to that, too, showed sharp differences by institutional station, as seen in the table below.

Presidents who said they were not confident in their college’s financial stability over five years were five times likelier than those who were confident to see merger or closure as possible, while those who said they had had serious discussions about merging were almost 10 times likelier to see merger or closure in their near future.

Mergers remain something close to a nuclear option, though, since in most cases higher education mergers are absorptions in which one institution largely disappears -- something few campus leaders (let alone alumni or employees) want to contemplate.

More likely -- but apparently much more desirable than possible, in presidents’ eyes -- is the prospect of consolidating academic programs or administrative operations.

Nearly a third of all presidents -- and more than a third of private college leaders -- say they’ve had serious internal discussions about such consolidation.

Majorities of all presidents think their college or university should share administrative functions (55 percent) or combine academic programs (58 percent) with other institutions, including nearly two-thirds at private doctoral and master’s universities and about seven in 10 leaders of private four-year colleges.

But despite that strong inclination, no more than one in six presidents in any higher ed sector thinks their institution is likely to either share administrative functions or combine academic programs with a peer.

That reflects the long-standing view that colleges tend to operate more competitively than collaboratively, but it is likely to concern those who feel that we’re at the point where no college can afford to be an island unto itself.

Presidents take a moderate view of how many institutions other than their own face drastic financial futures, too. Presented with a range of possible outcomes for how many colleges will close and how many private and public institutions will merge in 2020, presidents on balance chose the low end:

- On closures, 27 percent said they expect five or fewer; 36 percent expect six to 10; 25 percent expect 11 to 20; and 11 percent foresee more than 20. There were eight such closures in 2019.

- Half of presidents expect one to five private college mergers; 35 percent envision six to 10, and 14 percent predict more than 10.

- Regarding public colleges, 81 percent of campus leaders predict no mergers (17 percent) or five or fewer (64 percent); 12 percent foresee six to 10; and 7 percent expect more than 10.

S&P's Wood described the presidents' views on mergers and consolidation as "consistent with what we would expect."

"While S&P has a negative outlook on the higher education sector," she said, "we are more concerned about the weaker institutions, which lack the size and scale, reputation and student draw, revenue diversity or balance sheet to compete as effectively as higher-rated organizations."

Wood also said it wasn't surprising that presidents envision more closures than mergers.

"Mergers are challenging to get done," she said. "So while some struggling colleges or universities with valuable real estate, brand or institutional core competencies will be able to secure an affiliation, merger or acquisition, we expect we will see more closures, in particular among smaller, more regional private liberal arts colleges."

Fewer than four in 10 presidents said they expected a “significant economic downturn” within 18 months, and while a small majority (53 percent) said they worried about the impact such a recession could have on their colleges, two-thirds (65 percent) agreed that their institution would be better prepared to deal with a downturn than they were the Great Recession of 2008. It's important to note that the survey was conducted in January and early February, before the threat of a pandemic requiring near-constant monitoring and shaking consumer confidence in ways that threaten to jump-start a recession.

Campus leaders were also asked a new set of questions this year about what might be called "change management." Presidents overwhelmingly (69 percent) believe their institutions need to “make fundamental changes in [their] business models, programming or other operations” -- a number Wood, of S&P, said she was surprised wasn't higher. "Almost every school we rate is looking at ways to evolve as the sector continues to change," she said.

Presidents seemed less sure of their ability to carry out such change. A majority, 54 percent, expressed confidence that their college “has the right mind-set to respond quickly to needed changes,” but a smaller number, 45 percent, said their institution had "the right tools and processes" to respond.

On both those counts, chief executives were more optimistic than respondents to Inside Higher Ed's survey of chief business officers were last summer: fewer than four in 10 financial officials said their institutions had the right mind-set or tools and processes.

The survey asked how much they can count on other key campus constituencies for support in dealing with the economic challenges they face and the possible changes they need to make. Not surprisingly, the vast majority of campus leaders (88 percent) agreed that other senior administrators on their campus "understand the challenges confronting my institution and our need to adapt."

Also not surprisingly, far fewer said the same about faculty members as a group, with 23 percent agreeing and 46 percent disagreeing that faculty understand the need to adapt.

One group -- trustees -- fell into the middle, with 64 percent of presidents agreeing that board members understand the challenges facing their institutions and the need to adapt. Given that board members give presidents their marching orders and support them -- or not -- when they make difficult choices, the presidents' lack of confidence in their boards suggests a possible problem for them.

The Role of Race

In 2014, when Inside Higher Ed first asked presidents to assess the state of race relations on college campuses, nine in 10 presidents decreed their own institutions to have "excellent" or "good" race relations, and more than half said so about all campuses. In 2016, after a spate of racial incidents rippled across higher education, the proportion rating higher education as a whole positively tumbled -- but presidents still rated their own campuses very positively, leading some observers to question whether the leaders were paying attention to their own backyards.

This year's survey changed only marginally. While the leaders' assessment of the national picture dropped to its worst ever, as seen in the chart below, and the proportion of presidents rating race relations on their own campuses as excellent fell to 14 percent from 18 percent, the vast majority still took a positive view.

Asked for comment on the trend line, Beverly Daniel Tatum, president emerita of Spelman College and a national expert on race relations, did the virtual equivalent of throwing up her hands, saying she had nothing new to say beyond her comments on last year's survey, which were, "Are today's presidents really tuned in to what is happening in residence halls and fraternity houses and on student social media in the Trump era? … Do presidents feel that race relations are 'excellent' or 'good' because they have created dynamic opportunities for cross-racial engagement on campus, both in and outside the classroom, or because the campus is 'quiet' and protests have subsided? I would be very curious to know what the indicators are that presidents are using when they answer these questions."

On a somewhat related topic, presidents expressed stronger support for consideration of race and ethnicity in admissions decisions than they did a year ago, perhaps emboldened by last October's federal court ruling upholding Harvard University's affirmative action policies. Sixty-seven percent of presidents strongly agreed (34 percent) or agreed that colleges should continue to consider race and ethnicity, with 18 percent disagreeing.

The Harvard ruling may also have influenced presidents' views on whether Asian American applicants to top colleges face discrimination, as the plaintiffs in the case argued. Last year 42 percent of presidents said they shared that worry, and 24 percent disagreed. In this year's survey, fewer presidents agreed (37 percent) and a smaller proportion disagreed (33 percent), as Harvard maintained (and the judge ultimately agreed). The case is on appeal, though, and could go all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Another major issue raised in the discussion surrounding the Harvard case was admissions preferences for the children of alumni, which many supporters of race-conscious admissions have cited as one of many advantages that have historically benefited wealthier people in college admissions.

Support for the use of legacy preferences has declined in the last year, with 46 percent of presidents agreeing that they are appropriate for private colleges to use and 20 percent seeing them as appropriate for public colleges. In 2019, those figures were 52 percent and 24 percent, respectively.

Views on Federal Policy

Many states and communities have embraced policies that provide free tuition at all public colleges (or at least community colleges) for qualified students, and public support for the idea is strong. The idea has captured the fancy of many Democratic politicians, although it has stronger backing among supporters of Bernie Sanders than, say, Joe Biden.

College presidents aren't fans. Just 22 percent agree with the statement "I support the idea of free public college," and community college presidents (at 47 percent) are 30 percentage points more supportive than those in any other sector (public master's/baccalaureate university presidents are next at 15 percent). Private college presidents are, unsurprisingly, overwhelmingly opposed, with seven in 10 strongly opposed.

That response confounded Morley Winograd, whose group, the Campaign for Free College Tuition, advocates for free college programs.

"I have rarely seen a group of leaders of organizations more out of touch than this survey of college presidents shows they are with Americans," Winograd said, citing his group's recent survey finding three-quarters of Americans -- and even 62 percent of Republicans -- favor "your state providing free tuition at public universities and colleges for anyone who is academically qualified."

Winograd further cited results from the survey in which presidents overwhelmingly said they believed that "attention to student debt has led many prospective students and parents to think of college as less affordable than it is, taking into account student aid" (85 percent agree), and that "confusion about tuition sticker prices and tuition discounting have led many prospective students and parents to think college is less affordable than it really is" (82 percent agree).

"They're agreeing that there's a really bad taste in the mouth of many students and parents" on affordability, but "they don't seem to acknowledge that it's there because of some things they're doing," like having inscrutable pricing policies, Winograd said.

Lanae Erickson, senior vice president for social policy and politics at Third Way, a think tank that favors what it calls "modern center-left ideas," said via email that campus leaders deserve credit for not endorsing "bumper sticker ideas like free college and debt cancellation," even though free college would actually be a financial boon to those at public colleges. "These ideas may sound good at a political rally, but they have shockingly few proponents when you talk to the folks who actually understand what they mean and the impact they would have on students and on the American higher education system," Erickson said.

Erickson said she was surprised -- and pleased -- that more presidents supported (40 percent) than opposed (31 percent) the Education Department's publication last fall of data on the debt levels and postcollege incomes of graduates from specific programs at colleges that award federal financial aid.

"It’s a sign just how far the institutions have moved," she said. "It’s shocking, really -- can you imagine the uproar if the Obama administration had released such data in their first term? The conversation has really moved, and clearly these presidents realize times are changing and they can’t stop the tide."

Julie Peller, a former Democratic congressional aide who now runs Higher Learning Advocates, another policy group, echoed that view.

"Access to that data is essential for students," she said. "When entering or returning to higher education, today’s students look for specific programs just as much as they look for institutions, and it’s important that they have access to accurate information about their potential debt and possible earnings when making decisions about where to enroll."

The other major federal policy area the survey explored was the Trump administration's recent intensification of scrutiny of the role of Chinese and other foreign researchers in U.S. science. More presidents disagree (45 percent) than agree (28 percent) that the increased scrutiny "is reasonable given legitimate concerns about theft of intellectual property and national security," and a majority (52 percent) believe the scrutiny results in "racial profiling of Chinese faculty members and graduate students"; 24 percent disagree.

But presidents of those institutions closest to the issue are divided: slightly more leaders of public doctoral universities agree (36 percent) than disagree (34 percent) that copyright and security concerns justify scrutiny of international researchers (though 67 percent agree that racial profiling is going on).

A few other findings of the Inside Higher Ed presidents' survey on politics and higher ed's image:

- Presidents expressed skepticism that Congress would renew the Higher Education Act before November's election (47 percent said they didn't expect it to happen, while 29 percent did).

- Sixty-nine percent of campus leaders said they worry about "Republicans' increasing skepticism about higher education," up from 66 percent a year ago. The leaders of public regional comprehensive colleges (80 percent) are especially concerned.

- More than half of presidents (57 percent) said the perception of colleges as intolerant of conservative views was hurting public attitudes about higher education, about similar to last year (59 percent). But fewer presidents this year than last year (28 percent versus 37 percent in 2019) agreed that the "perception of colleges as places that are intolerant of conservative views is accurate," and slightly more presidents (65 percent) agreed that their campus's classrooms were "as welcoming to conservative students as they are to liberal students" (62 percent said so in 2019).

- Asked what they considered most responsible for declining public support of higher education, presidents put concerns about affordability and student debt at the top (96 percent), followed by colleges' record preparing students for careers (92 percent), the perception of liberal bias (78 percent), low or lagging graduation rates (73 percent), and underrepresentation of low-income students (51 percent).

The Price of Textbooks

College presidents are sympathetic to criticism about the costs of textbooks -- 89 percent agree textbooks and course materials cost too much, including 59 percent who agree strongly. They also strongly support the use of open educational resources -- freely available and openly licensed curricular materials -- to bring down those costs.

By 48 percent to 30 percent, presidents agree rather than disagree that faculty members and institutions should be open to changing textbooks or materials, even if the lower-cost options are of lesser quality. The proportion of presidents who hold that view is up from 39 percent a year ago. More presidents -- 59 percent, up from 51 percent last year -- also agree that the need to help students save money justifies the loss of some faculty control in choosing course materials.

As seen in the table below, the presidents' views on those methods of lowering students' textbook costs put them at odds with the perceptions of faculty members, as measured by Inside Higher Ed's 2019 Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology: