Free Download

“Embrace” is probably too strong. “Acquiescence” suggests too much passivity. Whatever word you choose, though, the data indicate that American faculty members -- whether grudgingly or enthusiastically -- are increasingly participating in and, to a lesser extent, accepting the validity of online education.

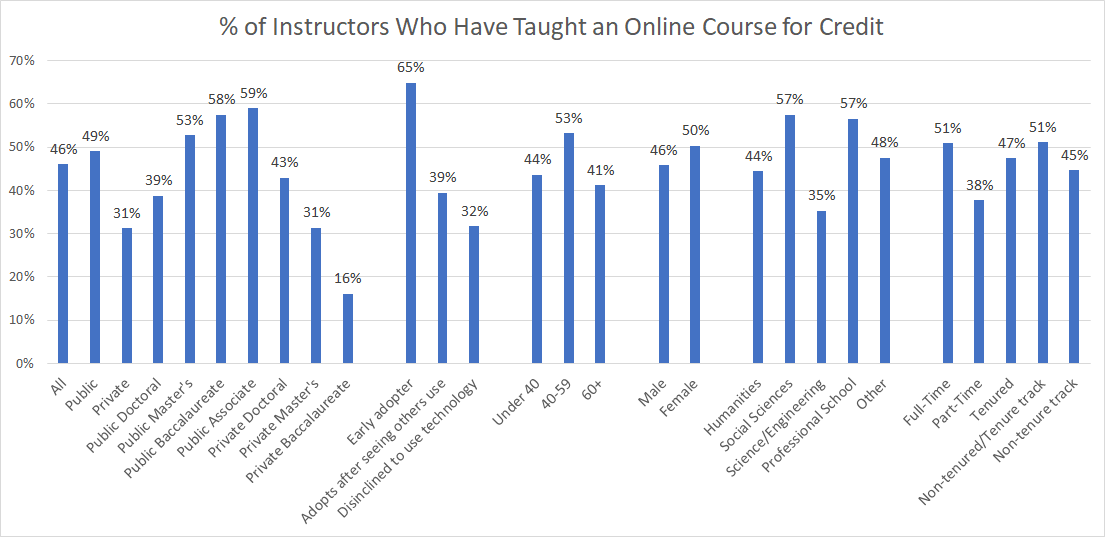

Inside Higher Ed's 2019 Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology, conducted with Gallup and published today, shows a continuing uptick in the proportion of faculty members who have taught an online course, to 46 percent from 44 percent last year. That figure stood at 30 percent in 2013, meaning that the number has increased by half in six years.

Lest anyone think that that trend means professors have fully embraced the value and benefits of online education, though, think again. While three-quarters of instructors who have taught online believe it made them better teachers in several key ways, professors remain deeply divided about whether online learning can produce student learning outcomes equivalent to face-to-face instruction.

The survey, which can be downloaded here, explored the views of 1,967 faculty members and 178 administrators who oversee their campuses' digital learning efforts about a wide range of technology and other issues.

About the Survey

Inside Higher Ed's 2019 Survey of

Faculty Attitudes on Technology was

conducted in conjunction with

researchers from Gallup. You may

download a free copy here.

Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys

key higher ed professionals on a range

of topics.

On Thursday, Dec. 5, at 2 p.m.

Eastern, Inside Higher Ed will present

a free webcast to discuss the

results of the survey. Register

for the webcast here.

The Inside Higher Ed Survey of

Faculty Attitudes on Technology

was made possible in part with

support from Sonic Foundry,

Course Hero and Portfolium.

Among the new survey's other findings:

- Nearly four in 10 instructors (39 percent) say they fully support the increased use of educational technologies, up from 32 percent in 2018 and 29 percent in 2017.

- Neither faculty members nor digital learning administrators believe online learning is less expensive to offer than its on-ground alternative -- unless colleges reduce spending on instruction or student support.

- Majorities of professors and digital learning leaders alike generally oppose colleges' use of external vendors to deliver online academic programs, except for marketing to students.

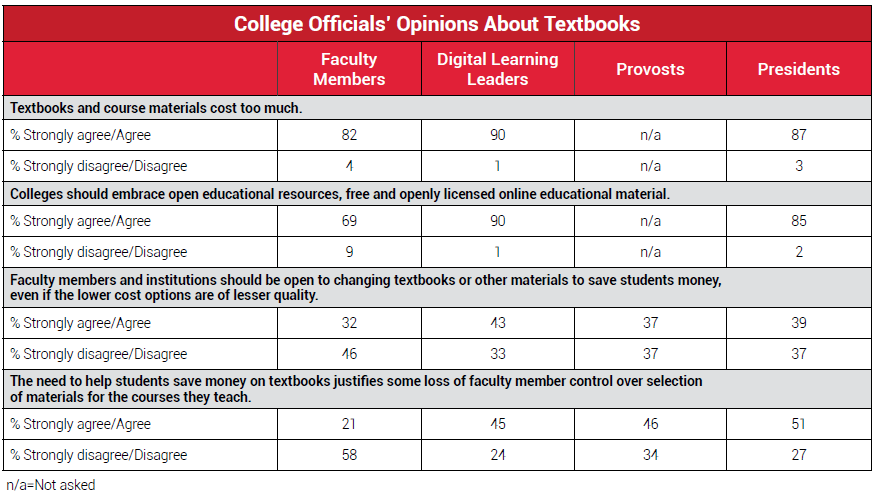

- Professors believe textbooks are too expensive and support use of open educational resources as an alternative -- but they are reluctant to put price ahead of quality or to give up control over selection of instructional materials.

- Six in 10 faculty members believe academic fraud is more common in online courses than in face-to-face courses, while the rest believe fraud occurs equally in both settings.

Practice vs. Philosophy

The quest to understand the faculty relationship with the use of technology to deliver instruction starts with a look at behavior.

Since Inside Higher Ed began surveying faculty attitudes on technology in 2012, first with the Babson Survey Research Group and then with Gallup, the proportion of instructors who say they have taught at least one online course has risen significantly.

As seen in the chart below, which begins with Gallup's first iteration of the survey in 2013, that percentage has grown from three in 10 and seems on an inexorable march toward half and beyond.

The growing proportion of instructors who have taught online is a logical outgrowth of the fact that more colleges are embracing online learning to reach students they couldn't otherwise enroll and to respond to demands from students for more flexibility in when and how academic programs are offered.

While faculty participation in online learning continues to edge up over all, it is extremely uneven -- by institution type, discipline and mind-set. As seen in the table below, public college instructors are far likelier than their private college peers to have taught an online course; midcareer professors are more likely to teach online than are their younger or older peers; and social science and professional school faculty members are likelier to teach online than their science and humanities counterparts.

A plurality (41 percent) of instructors who have taught an online course have done so for fewer than five years, while a third (34 percent) have taught for between five and 10 years, and a quarter (25 percent) have taught for more than 10 years.

Those who have taught online overwhelmingly believe it has made them better at their jobs.

More than three-quarters (77 percent) of those who have taught online courses say the experience has helped them develop pedagogical skills and practices that have improved their teaching.

When those instructors were asked how their online experience has most improved their teaching skills, 75 percent said they think more critically about ways to engage students with content. Other common answers were making better use of multimedia content (65 percent), being more likely to experiment and make changes to try to improve the learning experience (63 percent), making better use of their institution’s learning management system (61 percent), and aligning content and assessments more closely with course learning objectives (58 percent).

And more than two-thirds of instructors who had converted a face-to-face course to an online or hybrid (blended) class said that their time spent lecturing declined (65 percent) and that they incorporated more active learning techniques into the new course (69 percent).

"Improving course design and teaching in all modalities is a common outcome for those who undergo training for online course development and teaching," said Shannon Riggs, executive director of course development and learning innovation at Oregon State University's Ecampus.

Lingering Doubts

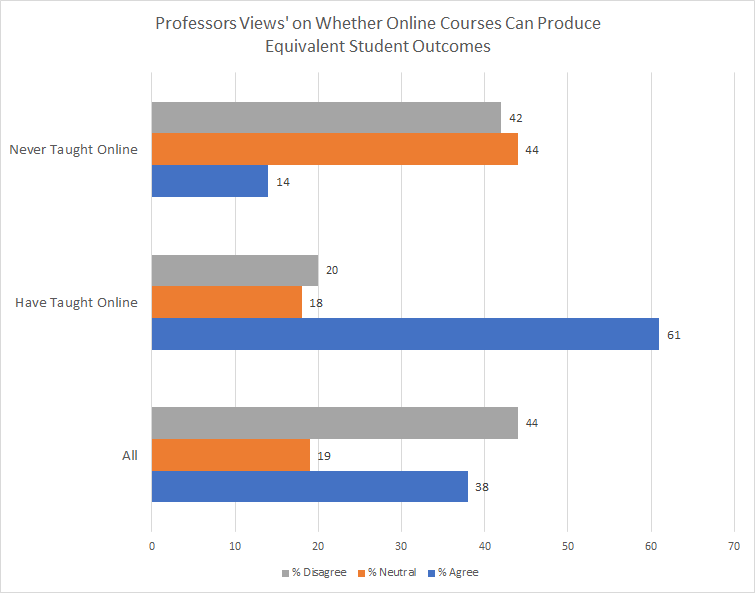

Even as more faculty members teach online, they continue to question whether online education produces student outcomes equivalent to in-person courses -- although their impressions improve the closer they get to what they know firsthand.

As seen in the chart below, slightly more faculty respondents disagree (36 percent) than agree (32 percent) that "online courses can achieve student learning outcomes at least equivalent to in-person courses at any institution" -- presumably representing their overall view of online education. (The other 32 percent of respondents chose a middle ground.) Those figures have remained largely steady in the last three years of the Inside Higher Ed survey.

The situation looks a little different as the aperture narrows to what they know more personally. Thirty-eight percent agree (and 33 percent disagree) that online courses can achieve student outcomes equivalent to those of in-person courses at their institution, with 29 percent unsure.

And when asked about the efficacy of online learning in the courses the instructors teach themselves, 38 percent agree -- and 44 percent disagree, with just 18 percent taking a middle ground.

The ratios change significantly by subgroup of faculty members. Community college instructors, for instance, are more likely to agree than disagree that online learning can achieve equivalent outcomes in the classes they teach by a 53 to 31 percent margin, while the ratio for private college baccalaureate professors is 15 percent agree to 72 percent disagree.

Forty-six percent of female professors agree and 36 percent disagree with that statement, while the ratio for men is 31 percent agree vs. 49 percent disagree.

And the biggest divide of all, not surprisingly, comes among those who have taught online vs. not, as seen in the chart below: 61 percent of those who have taught online agree that outcomes can be at least equivalent, compared to 14 percent of those who have not taught online.

The belief in the efficacy of online learning stands in stark contrast to the views of the digital learning leaders included in the survey, 89 percent of whom agree that online courses can achieve the same educational outcomes as face-to-face courses.

Why So Much Skepticism?

The survey provides some evidence for why such a gap remains, and why many faculty members remain skeptical about online learning.

Respondents were asked whether they'd describe themselves as an "early adopter" of technology, as someone who typically adopts technologies after seeing peers use it effectively or as disinclined to use educational technologies.

Nearly three-quarters of digital learning leaders (72 percent) put themselves in the first category, and the rest in the second.

About a third (35 percent) of faculty respondents characterized themselves as early adopters, with a majority (54 percent) in the follower category. One in 10 described themselves as opposed to technology.

Similarly, when asked to indicate their "level of comfort" with the increased use of educational technology, 86 percent of digital learning leaders said they "fully support" such use, as did about four in 10 faculty members (39 percent). The faculty number represents a marked increase in recent years, up from 32 percent last year and 29 percent in 2017.

Roughly the same proportion (41 percent) of instructors this year said they "somewhat" support technology in the classroom; the rest were either neutral or opposed.

The faculty members who support educational technologies cite helping students as the reasons why. Nearly two-thirds (64 percent) say they support the use of technology because "some students simply cannot attend a face-to-face class due to work or family obligations," and 57 percent "believe students learn better when I engage them with effective technology tools."

The instructors who oppose the use of academic technology do so, meanwhile, for a mix of student-facing and philosophical reasons. Two-thirds (65 percent) express confidence that "instruction delivered without using technology most effectively serves my students," but the next most-cited reasons are that "there is too much corporate influence" (47 percent), that "I don’t believe the benefits to students justify the costs associated with adoption" (41 percent) and that "faculty lose too much control over the course when they use technology" (35 percent).

It's also clear that faculty members continue to feel they get inadequate support from their institutions to use technology effectively -- even as they see that support generally improving.

Professors were asked to rate their institutions on their policies and overall environment for supporting the use of technology, especially online learning.

Colleges scored well on some counts: having a climate that encourages experimentation with new approaches to teaching (56 percent of professors agree their institution has such a climate) and providing adequate technical support for creating and teaching online courses (52 percent agree for both), for instance.

But none of the other eight categories received agreement from a majority of respondents, and some -- "acknowledges time demands for online courses for workload" (25 percent), appropriately rewards contributions to digital pedagogy (22 percent), rewards teaching with technology in tenure and promotion decisions (22 percent), and compensates fairly for development of an online course (22 percent) all received consent from under a quarter of instructors.

The latter categories include areas that colleges are going to have to do a better job of if they want to build long-term faculty buy-in for the use of technology.

Faculty members are smart: they pay attention to what the institution truly seems to value and what will help them in their careers. So if colleges and universities don't reward behaviors such as teaching with technology or digital pedagogy in promotion and tenure decisions -- and digital learning leaders largely agree with professors that their institutions don't value those things -- they probably can't expect instructors to do what they're not rewarded for.

"The disconnect [between instructors' views and those of digital learning leaders] this far along in the game is pretty big," said Vincent J. Del Casino Jr., provost and senior vice president for academic affairs at San Jose State University. "My sense is that at institutions that invest in thinking about online education as a new pedagogical way to reach students, you're going to see satisfaction go up, compared to places where there's a more mass-production, canned sort of courses.

"There seem to be a lot of institutions where faculty are told to teach online, and there's not as much of an intersection with support," he added. "When that's the case, the professors probably feel like they can't really transfer what they do into online -- all they can do is swim as fast as they can. We have to do better than that if we want faculty to believe they can be effective."

How Professors Build and Teach Their Online Courses

Last year's survey asked an expanded set of questions about how faculty members work with instructional designers -- and the answers were distressing to those staff members whose job is to help professors make their online courses great. Only a quarter of respondents said they had worked with a designer on an online or blended course, and fewer than half of those who had taught online said they had worked an instructional designer -- even though 87 percent said they were involved in designing their online courses.

This year's survey expanded the questions yet again, to try to get a better sense of the resources instructors were using in building and teaching their online and blended courses.

Exactly half of faculty members who have taught an online course for credit said they had built all their online courses from scratch themselves, and another 19 percent said they had built most of their online courses by themselves.

Seventeen percent said they had built all or most of their online courses with the help of an instructional designer, and 14 percent said they had inherited the courses from another faculty or staff member.

Seeking to get more insight into the sources instructors tap in to for advice, the survey asked respondents which resources were most helpful (they could choose up to three) as they designed or delivered online or blended courses.

Advice or insights from fellow faculty members at their institutions led both lists (for course design and delivery, at 56 and 53 percent, respectively). On designing courses, professors also listed instructional designers and IT support staff at their institutions (32 percent each), students (at 29 percent), and their institution's teaching and learning center (25 percent).

On teaching and delivering courses, faculty colleagues were followed by insights or advice from students (44 percent), IT support staff (30 percent) and instructional designers (25 percent).

"Faculty who are engaged with online course design and teaching often have much to share with colleagues," said Riggs of Oregon State. "We encourage faculty-faculty sharing at Oregon State Ecampus with our annual Faculty Forum event, an on-site conference where faculty share with other faculty their innovations, best practices and experience with online teaching. We also host smaller faculty luncheons quarterly to keep the sharing going throughout the year."

Too Much for Textbooks

Student concerns about the price of curricular materials continue to mount -- and the faculty is right there with them (up to a point).

Professors overwhelmingly agree (82 percent) that textbooks and course materials cost too much and that colleges should embrace open educational resources as an alternative (69 percent).

But fewer than a third of instructors (32 percent) agree that professors and institutions "should be open to changing textbooks or other materials to save students money, even if the lower-cost options are of lesser quality," and about a fifth (21 percent) agree that "the need to help students save money on textbooks justifies some loss of faculty member control over selection of materials for the courses they teach."

On those latter questions, there is significant daylight between the views of professors and other campus administrators queried in recent Inside Higher Ed surveys, as seen in the table below.

Instructors seem optimistic -- if still uncertain -- about the possible value of the traditional textbook publishers' approach to lowering student spending on textbooks: "inclusive access" subscription programs, which make digital course content available to students on the first day of class at a discounted rate that is often included as part of tuition.

About four in 10 professors said they believed the programs were achieving twin goals of reducing the cost of course materials and improving education outcomes, about a third said inclusive access was lowering costs but not improving access, and 20 percent said the programs did neither.

Nearly three in five instructors (59 percent) said it was too soon to say whether inclusive access was good for students, and about two-thirds (67 percent) said the adoption of such platforms by their institutions might limit faculty choice of course materials.

The Faculty Assessment of Assessment

Professors continue not to think very highly of efforts to assess how much students learn at their institutions -- but their opposition seems to be waning.

Don't get us wrong: they're not fans. Nearly half of instructors (49 percent) say their college's use of assessment is "more about keeping accreditors and politicians happy than it is about teaching and learning." And barely a third of professors agree that "these assessment efforts have improved the quality of teaching and learning at my institution" (33 percent) and that they "have received data derived from these efforts to improve my teaching" (34 percent).

But in 2018, 59 percent agreed with a (slightly different) statement that "assessment efforts seem primarily focused on satisfying outside groups such as accreditors or politicians." And just 25 percent agreed that assessment has improved the quality of teaching and learning at their institutions.

Cost and Price

Faculty members are evenly divided on whether "it is less expensive to offer an online course than an in-person course" -- 37 percent agree and 40 percent disagree. More than half of digital learning leaders, by contrast, disagree (55 percent, 33 percent strongly).

Both groups are more likely to disagree than to agree that online courses should be priced lower than in-person courses, and they are more likely to agree than to disagree that "online courses cost less than in-person courses only if institutions reduce their spending on faculty, student support or other important factors." Fifty-four percent of instructors agree with the latter statement, compared to 46 percent of digital learning leaders.

Instructors are more pessimistic about the ultimate promise of online education than their administrator peers, though. Forty-five percent of professors agree (31 percent disagree) that "there is an inevitable trade-off between price and quality in college courses," while digital learning leaders are more likely to disagree (61 percent) than to agree (23 percent)

Outside Vendors

One of the most significant areas of agreement between faculty members and administrators who oversee online education is a surprising one: their general distaste for using outside firms to build and manage their online academic programs. The companies are widely used by colleges, but their use is coming under increasing scrutiny from politicians and some college leaders.

Majorities of faculty members and of digital learning leaders oppose the use of external companies to provide a range of functions, including instructional design, offering student support, developing educational content or training the faculty.

The only area in which a majority of online education administrators (61 percent) and a near majority of faculty members (44 percent) favor the use of outside companies is in marketing to prospective students.

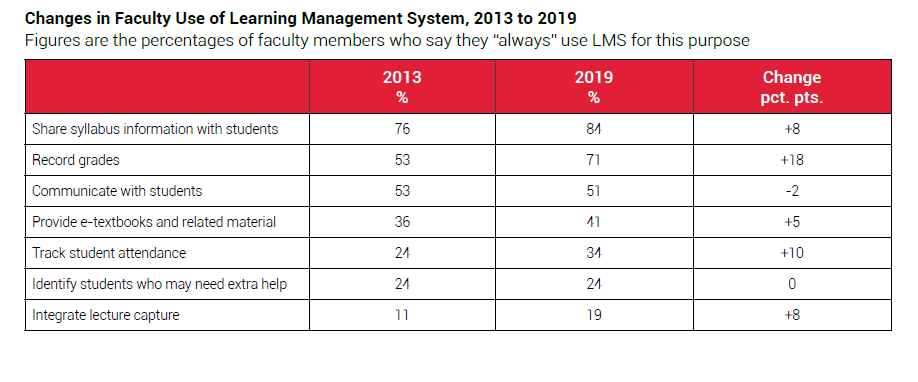

Learning Management Systems

Most colleges have technology platforms to deliver their online courses and manage some aspects of their in-person courses. But getting instructors to use the systems -- and for more than taking attendance -- has remained a struggle.

The chart below shows how faculty members say they are using their institution's LMS now -- and how that compares to previous years of the survey.

Among other findings:

- Slightly more than two-thirds of instructors say their institution offers training on how to make course materials compliant with the Americans With Disabilities Act. And the number of professors who say their courses include services that make them accessible to students with disabilities, including screen-reader capability, alternative text to visual elements and video captions, and audio transcription, are all up from 2018.

- Three in five professors say they believe academic fraud occurs more often in online courses than in face-to-face courses. The rest say cheating occurs in both settings about equally. Digital learning leaders disagree: 86 percent say fraud happens in both settings equally.