Free Download

In mid-March, as the novel coronavirus was taking hold on many campuses, Inside Higher Ed surveyed college presidents and found them to be focused on the job at hand: ensuring the physical and psychological safety of students and employees and enabling the smoothest possible transition to remote learning, for faculty members and students alike.

Yes, they acknowledged the threat of major financial and enrollment damage to their institutions and were beginning to think about how their institutions might adapt to a landscape that could be permanently altered by a crisis that some say may be the biggest since World War II. But the focus was on emergency response, on the "now."

Exactly a month later, in mid-April, Inside Higher Ed and its survey partner, Hanover Research, went back to them again with a similar but slightly expanded set of questions. The new survey of 187 two- and four-year college presidents, published today and available for free download here, offers a look at how campus leaders' views and actions are evolving as the COVID-19 pandemic and the recession it has spurred become the new status quo. The presidents, like all of us, continue to be bedeviled by a dearth of clear information about the arc of the health crisis and how and when some semblance of normalcy will return.

Among the findings:

- Focus on the most vulnerable students. Student and employee mental health, student attrition and unbudgeted financial costs remain near the top of presidents' list of short-term concerns, and potential enrollment declines and threats to financial stability trouble them for the long term. But they say their primary concerns in the immediate and long term are about the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on low-income and underrepresented students, a recognition that even in the best of times those students are most vulnerable to seeing their educations derailed and their personal well-being threatened.

- New investments. Many more presidents in April than in March said their institutions had invested in key services for students and employees: new online learning resources (69 percent in April, compared to 43 percent in March), emergency response resources (52 percent versus 44 percent in March), and additional physical and mental health resources (36 percent versus 18 percent).

- Uncertain timeline for fall. Presidents remain unsure about when students might return to their campuses. Nearly half, 47 percent, said they expected to return the majority of courses to an in-person format by the start of the fall semester. But a full third, 34 percent, said they had an uncertain timeline for reopening.

About the Survey

"Responding to the COVID-19 Crisis, Part II: A Survey of College and University Presidents" is available, free, for download here.

The survey of 187 college leaders was conducted by Hanover Research on behalf of Inside Higher Ed.

Inside Higher Ed's editors will lead a webcast discussion of the survey's results on Thursday, April 30, at 2 p.m. Eastern. Please sign up here.

The survey was made possible by advertising support from Accenture, Campus Management, ECMC Foundation, Ellucian and Pearson.

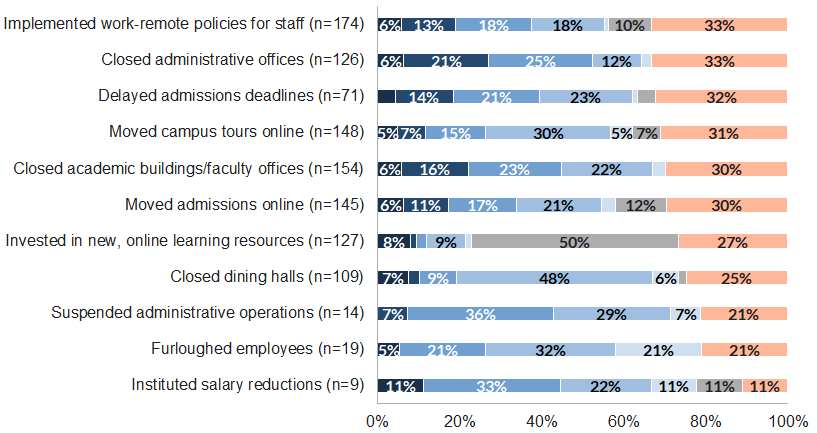

- Permanent changes? Some of the decisions presidents have made in the last month may end up being permanent. When asked when they might reverse actions they had taken in response to COVID-19, half said they would never undo the investments they'd made in new online learning resources, and between a quarter and a half said the same about investments in physical or mental health resources (40 percent) and emergency response resources (28 percent). But some campus leaders said they expected to make permanent the shift of admissions to an online format (12 percent), the freezing or reduction of benefits (12 percent), and the embrace of remote-work policies for employees (10 percent), among other actions.

- Employee cuts ahead. More pain for employees is almost certainly ahead. While fewer than two in 10 presidents said they had thus far reduced their workforces (19 percent), furloughed employees (10 percent), frozen or reduced benefits (9 percent), or cut salaries (5 percent), between a third and two-thirds said they were very or somewhat likely to take those actions in the future.

- Hopes for more revenue. Asked how they would address potential budgetary problems, presidents focused overwhelmingly on actions to increase revenue, with 80 percent or more saying they would cultivate new donors, seek additional state support or try to procure more grants. A third or fewer said they would reduce extracurricular offerings or change their tuition prices.

Changes in Short-Term Priorities

The survey is roughly divided into sections on the short term and the longer term, with questions about presidents' concerns and actions on both horizons. The differences between the two administrations of the survey, in March and April, offers insight into how presidents' priorities have changed as the situation has evolved.

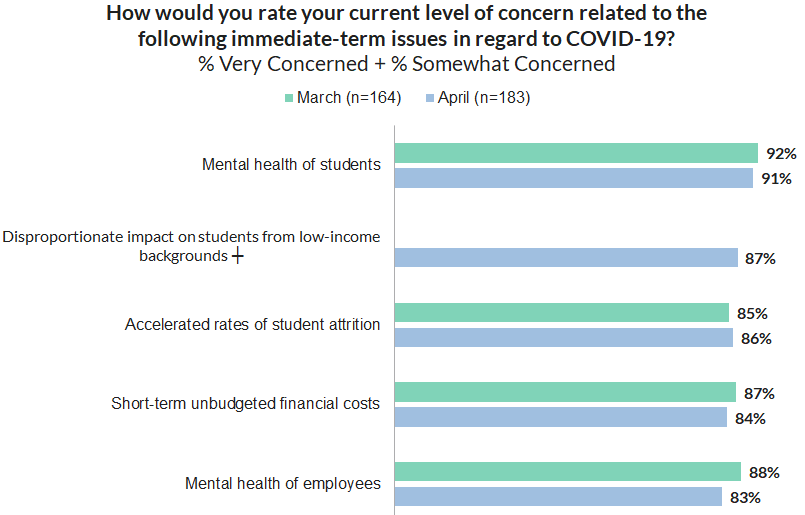

The mental health of students remains presidents' very top concern in the near term -- and even more so than is evident in the graphic below. The proportion of college leaders saying they are "very concerned" about student mental health grew to 47 percent in April from 37 percent in March. In most other areas posed to presidents in March and April alike, campus leaders expressed modestly less concern as time went on, including about students' physical health and faculty readiness to conduct digital learning.

But Inside Higher Ed asked presidents to respond to one additional area of possible concern in March: disproportionate impact of the coronavirus epidemic on students from low-income backgrounds.

More than two-thirds of presidents, 68 percent, said they were very concerned that needy students would be disproportionately hurt as campuses responded to COVID-19, more than for any other issue. Seventy-five percent of presidents of four-year public universities and 73 percent of community college presidents responded that way, as did 59 percent of chief executives of four-year private colleges.

Advocates for low-income students were gratified by the presidents' priorities. "I'm surprised and pleased, actually," said Dale Whittaker, former president and provost at the University of Central Florida, where nearly four in 10 students are eligible for Pell Grants for needy students. "I thought financial stability would be first, enrollment second and equity third, maybe by a good distance. This shows people are really concerned, that they really care."

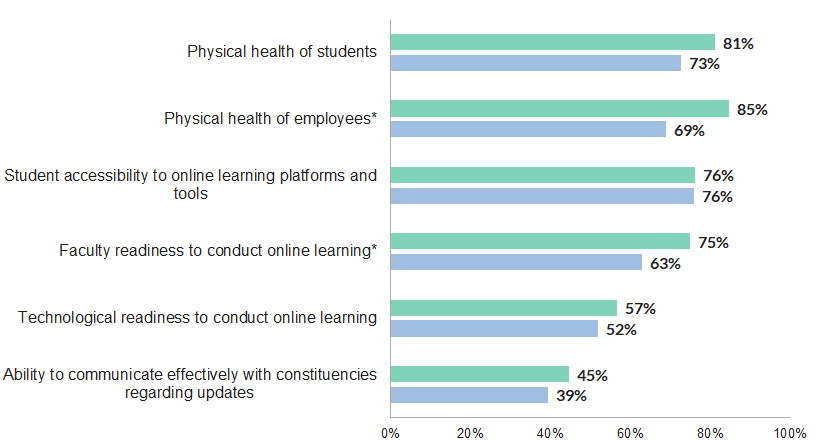

The other question about the immediate term related to which actions presidents have already taken on their campuses in response to COVID-19. The chart immediately below shows the actions that presidents said they had taken by mid-April; the most-taken actions included steps most colleges took immediately (moved to remote instruction for students and remote work for employees, closed administrative offices) and those done as they began shifting their focus to next fall, such as moving their admissions processes and campus tours online.

Fewer than one in five presidents said their institutions had by mid-April taken actions that affected employees' jobs or pay, with 19 percent having reduced their workforces and 10 percent or fewer furloughing employees, freezing or reducing benefits, or cutting pay.

Community colleges were more likely to have reduced their workforces (25 percent versus 16 percent at private nonprofit colleges and 14 percent at four-year publics) and to have furloughed employees (14 percent versus 11 percent at four-year privates and 5 percent of four-year publics), while private institutions were modestly more likely to have frozen or reduced benefits (14 percent) or cut pay (8 percent).

Some of the actions in the above list were added to the survey in April and weren't asked of presidents in March. Comparing the differences in the actions that institutions had taken by mid-March with those they had taken by mid-April suggests that more college and university leaders had invested in key areas needed to keep their institutions operating effectively now and in the coming months. In March, 43 percent of presidents said they had invested in new online learning resources; by April, that had climbed to 69 percent. Similar increases occurred for emergency response resources (52 percent versus 44 percent in March) and additional physical and mental health resources (a doubling, to 36 percent from 18 percent).

Those data suggest that campus leaders increasingly recognized that they needed to prepare their institutions, now and in the future, to ensure high-quality digital instruction and help their students and to protect students' and employees' physical and mental health. Community college leaders were significantly likelier than their peers to have increased their spending in these areas: the proportion of two-year-college presidents who said their institution had invested in new online learning resources rose to 84 percent from 48 percent from March to April, for example.

When Will Colleges Undo Those Actions?

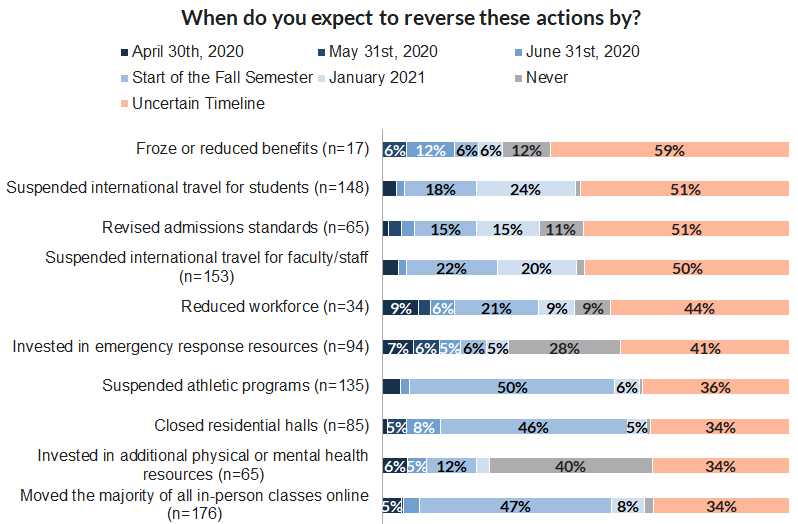

The March survey asked presidents when they expected to return to in-person instruction, and about a third (31 percent) predicted by fall, but more (41 percent) had an "uncertain timeline."

The April survey asked presidents that question in a slightly different way, by asking when they expected to reverse the entire set of actions they said their institution had already taken.

On the return to in-person instruction, presidents were more optimistic in mid-April than they were in mid-March that students would be back in classrooms by the fall, with nearly half of them saying so. Eight percent expected to return to in-person classes by next January, and about a third said they weren't sure.

When asked when they expected to reverse the broader set of actions their institutions had taken, several patterns emerge.

It's clear presidents have little line of sight about the course of the coronavirus and its potential impact on their campuses, with pluralities selecting the "uncertain timeline" option for many of the key questions facing their colleges, such as when students and employees may once again be able to travel internationally and when employees will return to work.

Another set of answers suggests presidents are counting on having their campuses reopen by the fall term -- perhaps too hopefully. A full half of campus leaders said they planned to undo the suspension of athletics programs by the start of the fall semester, and nearly half say the same about opening dining halls (48 percent) and residence halls (46 percent).

Presidents of four-year private colleges are by far the most optimistic -- perhaps because they collectively may be most in danger if a fall reopening of campuses is not possible. Fifty-four percent of leaders of private institutions said they expect to return to in-person classes by fall, and nearly two-thirds (65 percent) said sports programs would be in place by fall.

Looking Ahead

Most presidents are still up to their necks in responding to the current moment, so asking them to gaze too far into the future and think beyond the tactical may be too much. "I do think that right now they're so engrossed in the tactics of what they see as survival," said Timothy Tracy, former provost at the University of Kentucky and now a consultant.

Asked to rate their long-term concerns, presidents again put concerns about equity for certain students at the top of their list. Comparing their answers in April to those in March, more leaders say they are very or somewhat concerned about a decline in charitable giving rates (64 percent versus 56 percent in March) and a perceived decrease in the value of higher education (60 percent versus 48 percent).

Fewer, however, say they're worried about demands for room and board reimbursement (42 percent versus 55 percent in March) and especially demands for tuition reimbursement (35 percent versus 62 percent). That's despite numerous reports in Inside Higher Ed about class action lawsuits from students seeking such reimbursement -- and regular news releases Inside Higher Ed has received from lawyers discussing their plans to file such claims.

The declining concern about tuition reimbursement was driven mostly by a change in the view of four-year public college leaders. Only 28 percent of them reported being somewhat or very concerned about that possibility in April, down from 64 percent in March.

Again, analysts applauded the presidents' focus on vulnerable students. "The presidents' concerns long term about the impact on underrepresented students and individuals from low-income backgrounds are well founded," said Tracy, the former Kentucky provost, via email. "It will be critical for institutions to proactively reach out to these individuals and provide them with support services (financial counseling, academic counseling, emotional counseling, etc.) to help them navigate their options to enroll or to remain enrolled."

College leaders' concerns about their long-term financial stability and potential enrollment declines remain significant -- and the survey sought to gauge how likely they are to take certain actions to respond to those concerns.

First, presidents who had not yet taken the institutional actions described above were asked how likely they were to do so going forward. These answers are likely to trouble campus employees: nearly two-thirds (62 percent) of campus leaders who said they had not already reduced their workforce by mid-April said they would in the future, about half said they would furlough employees (49 percent) and more than a third said they would institute salary reductions (38 percent) or reduce benefits (36 percent).

The survey also asked presidents how likely their institutions would be to take a series of actions in response to potential revenue shortfalls or cost overruns. As is often the case in Inside Higher Ed's other surveys of presidents, they tended to favor the less controversial approaches that could increase revenue (cultivating new donor bases, seeking more state support) rather than attempts to control or lower their costs. Whittaker, formerly of Central Florida, said he was troubled that presidents seemed to focus their attention on "pies that are shrinking" or likely to shrink during a deep recession, such as state funds or fundraising pools.

Presented with a list of possible approaches to avoid or address potential enrollment challenges, presidents overwhelmingly said they were likely to optimize the academic programs they offer and increase financial aid. Slightly more than half (56 percent) said they would allow students to defer tuition, as some institutions have done, but fewer than one in 10 said they would lower tuition or adopt a sliding tuition scale based on student income.

Comparing the list of what presidents say are their top concerns with their preferred strategies for addressing them left Whittaker, the former Central Florida president and provost, questioning how well they were aligned.

Many institutions, he said, are facing budget reductions ranging from tens of millions to hundreds of millions of dollars, he said, depending on how long campuses are closed and how deep the recession is.

"That's more than a haircut -- that’s the kind of hit that may require organizational change," Whittaker said. Most colleges and universities are in "triage mode right now," focused on "saving the patient," and they're figuring out "where the patient hurts" and "trying not to cut off the leg if they don't have to." In many cases they're making those decisions "without the information you'd ideally have to make decisions."

The fact that leaders say they are prioritizing equity for low-income or underrepresented students is commendable, in Whittaker's view, but it may force difficult decisions, he said, such as "how to use $25 million in institutional financial aid … How much do we use to buy full-paying students from out of state versus using the money to help retain or recruit our neediest students."

As presidents and governing boards move out of triage mode, where they're focused on survival, they'll soon need to switch to the second and third phases, which involve resource reallocation and prioritization (if significant cuts are needed, as is likely for many colleges) and then transformation, or "fundamental reorganization or redesign."

In all three phases, he said, colleges and universities "need to be as true as possible to the institutional core mission -- who are we? Are we about reputation and excellence, such that we'd prioritize the student/faculty ratio and the personal residential experience? Or are we about equity of access and success?

"Those values should be laid up against every decision and in a transparent way."

Other Findings

The survey addressed a handful of other topics.

- The shift to remote instruction. In general, presidents seem to have been heartened by how their colleges managed the emergency transition away from in-person learning. Fewer of them in April than in March rated the shift as very or somewhat challenging in terms of training faculty members less familiar with digital delivery (68 percent in April versus 75 percent in March), ensuring that academic standards remained high (47 percent versus 59 percent), and having technology support available (36 percent versus 50 percent). The survey did not ask them to rate the challenge of providing high-quality digital instruction in the fall, when faculty and student expectations are likely to be significantly higher.

- Help from the government. Presidents overwhelmingly rated stimulus funds to compensate their institutions for financial losses (93 percent) as their greatest need from federal or state governments, followed by flexibility on regulatory limitations regarding remote learning (58 percent) and a mental health resource allocation for students (41 percent, up from 33 percent in the March survey).

- Assistance from other sources. Campus leaders continued to list "financial health and operational planning" as the top area in which their institution could benefit from outside operational support to navigate through the COVID-19 crisis. But they cited two areas much more in April than they did in May -- strengthening the perception of their institution's brand and institutional partnerships. The latter suggests that presidents are increasingly seeing the need and value of collaborating with peer institutions, which many experts have encouraged.