Free Download

College presidents overwhelmingly agree that Harvard University is justified in defending its use of affirmative action in admissions -- but far fewer believe it will prevail in its lawsuit.

Campus leaders largely believe Obama administration rules on sexual assault paid too little attention to the rights of the accused -- and that the Trump administration's response would edge too far in the other direction.

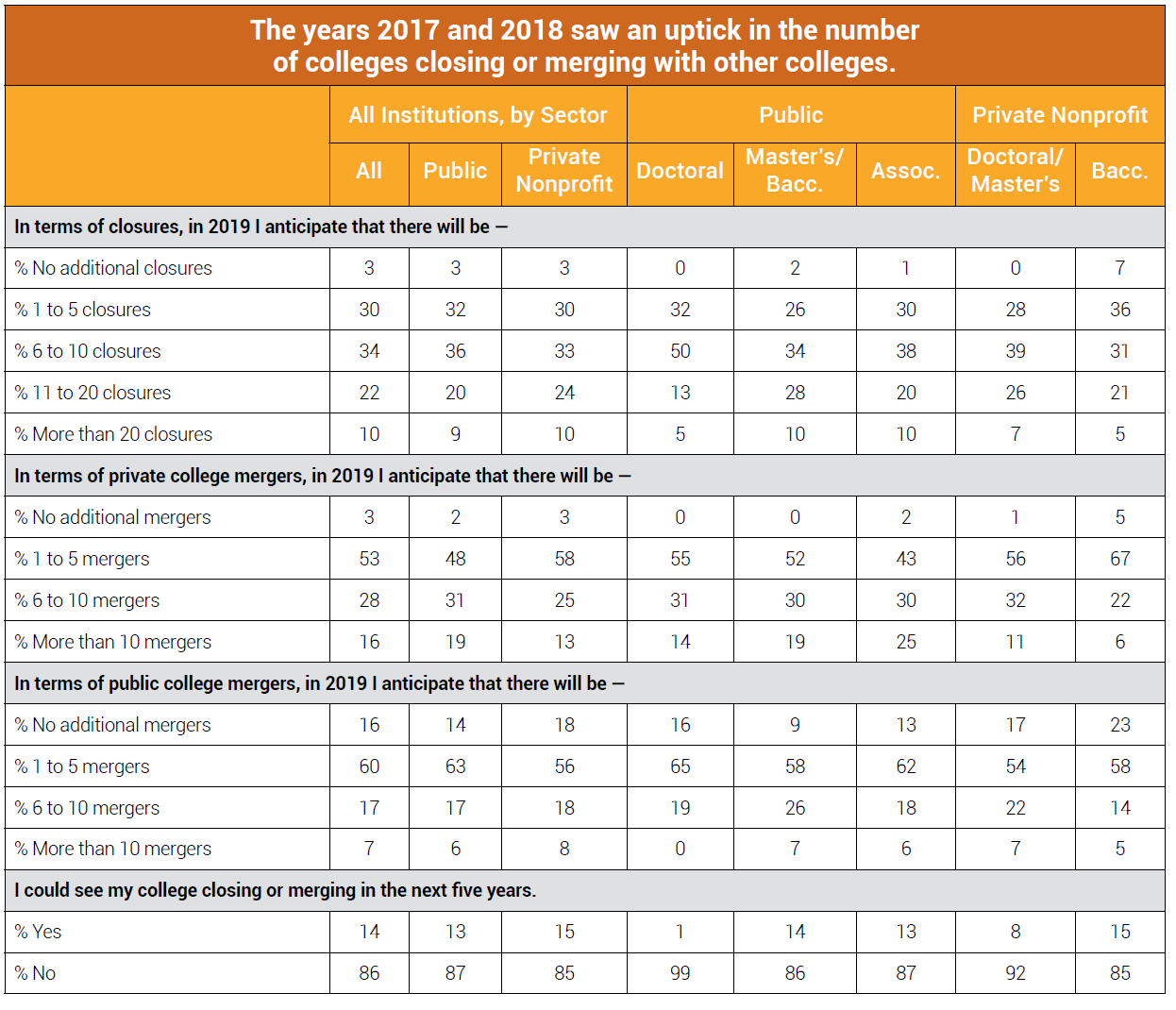

And presidents express more confidence in the 10-year financial stability of their campuses than they have at any point in the last six years -- but nearly one in seven says his or her campus could close or merge within five years.

More on the Survey

Inside Higher Ed's 2019 Survey of College and University Presidents was conducted by Gallup.

Inside Higher Ed regularly surveys key higher ed professionals on a range of topics.

Doug Lederman, Inside Higher Ed's editor, and a panel of presidents will present findings from the survey Monday at the American Council on Education's annual meeting in Philadelphia. Details are here.

On Tuesday, April 2, Inside Higher Ed will present a free webcast to discuss the results of the survey. Please register here.

The Inside Higher Ed Survey of College and University Presidents was made possible in part with support from Cengage, EY Parthenon, Jenzabar, the Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi, and Watermark.

Those are among the compelling and sometimes confounding findings of Inside Higher Ed's 2019 Survey of College and University Presidents, conducted with Gallup and released today in connection with the American Council on Education's annual meeting in Philadelphia. A copy of the survey report can be downloaded here.

The survey -- to which 784 chief executives of two- and four-year institutions responded -- finds presidents expressing more confidence (sometimes ever so slightly more) on some key issues, even as significant worries remain.

Among the key findings:

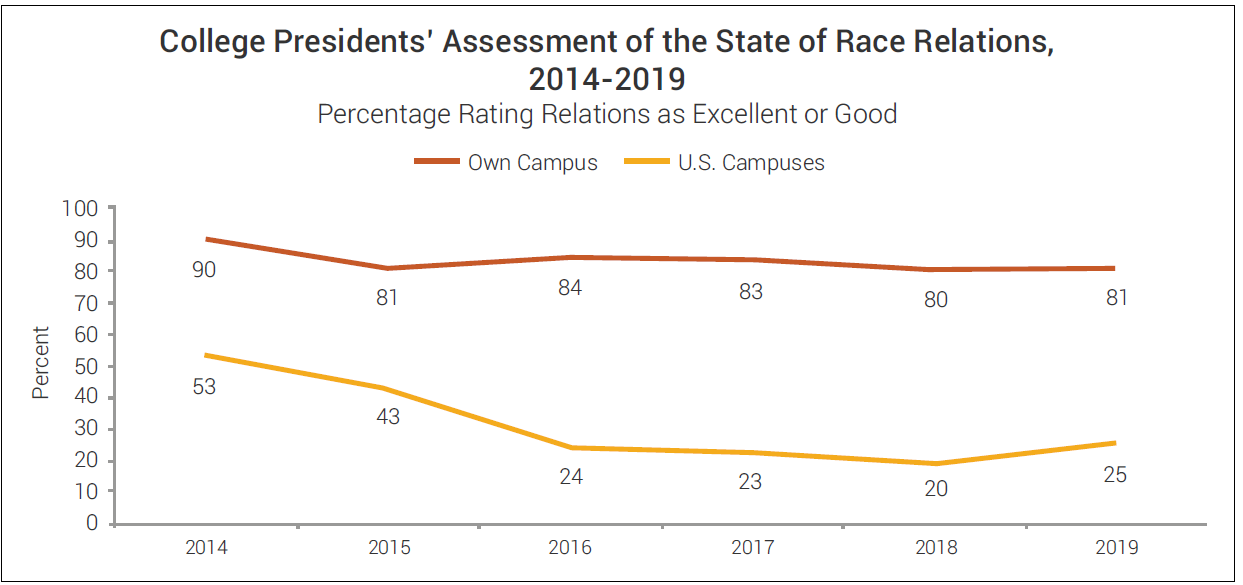

- One in four presidents describe race relations on college campuses nationally as good (24 percent) or excellent (1 percent), up slightly from last year's low of 20 percent. They view the situation on their own campuses much more favorably, with four in five rating race relations on their own campuses as good (63 percent) or excellent (18 percent).

- Fifteen percent of campus leaders say their institution has been offered large financial gifts with inappropriate strings attached, and a third (34 percent) say they had rejected gifts because of requirements on how the funds could be used. Presidents are divided on whether more donors are making inappropriate demands than in the past.

- Fewer presidents this year (66 percent) than in 2018 (77 percent) say they are worried about Republicans' increasing skepticism about higher education. But slightly more campus leaders this year (37 percent) than last year (32 percent) agree that the perception of colleges as places intolerant of conservative views is justified.

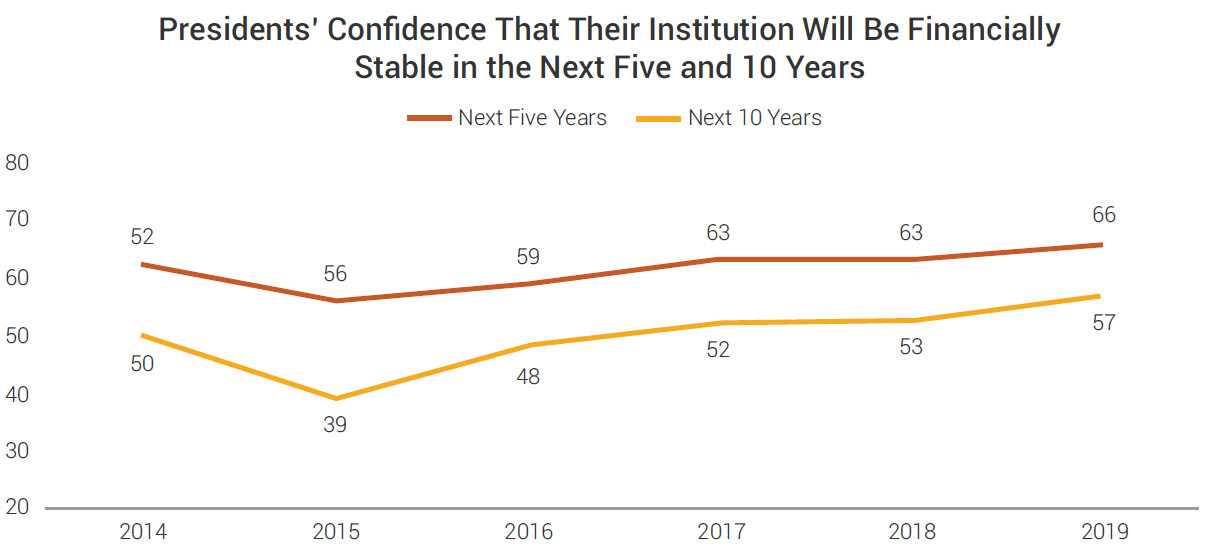

- Fifty-seven percent of presidents are confident in their institution's financial sustainability over a decade, up from 53 percent last year. Leaders of private four-year colleges are most confident (64 percent), public master's and baccalaureate college presidents the least (49 percent).

Affirmative Action and the Harvard Case

Not to tempt the journalism gods, but there is unlikely to be a bigger higher education news story in the next few months than a federal judge's ruling in the lawsuit brought against Harvard on behalf of a group of Asian American students. The case, closing arguments in which were delivered last month, alleges that the university's admissions policies favor black and Latino applicants at the expense of Asian American applicants. While Harvard is the formal defendant, affirmative action -- and selective colleges' use of holistic admissions, among other things -- are also on trial.

This year's presidents' survey asked a series of questions about the Harvard lawsuit and attendant issues, finding the respondents strongly supportive of affirmative action but nervous about the outcome and potential impact of the case.

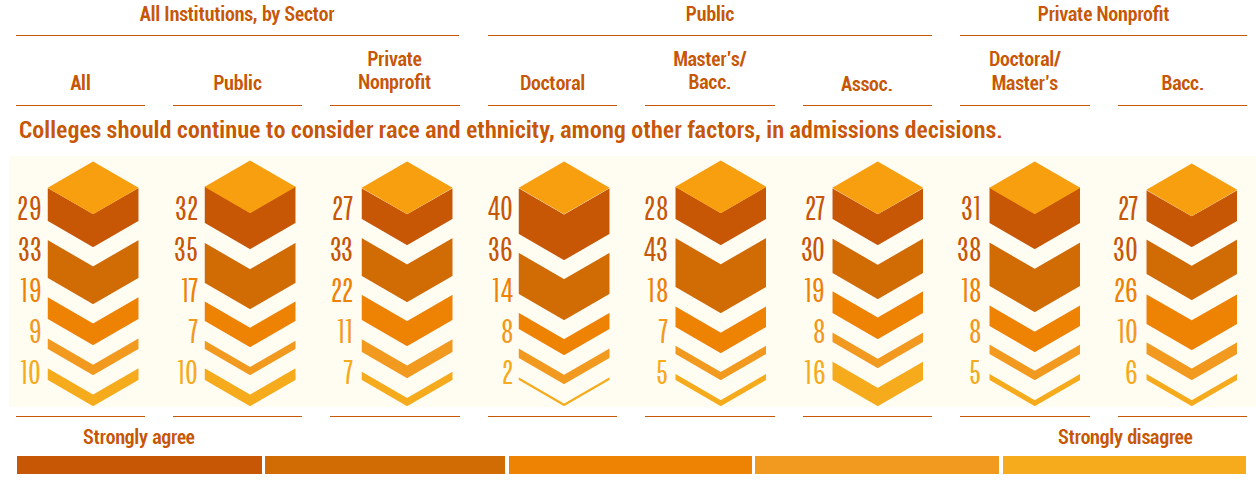

Strong majorities of presidents believe that colleges should continue to consider race and ethnicity alongside other factors in admissions decisions (62 percent) and that the public does not understand holistic admissions, in which selective institutions judge applicants on the totality of their individual records rather than on a rubric of grades and scores alone (79 percent). As seen in the graphic below, support for affirmative action was strongest among leaders of public doctoral and master's/baccalaureate universities and private doctoral and master's institutions, and weakest among community colleges and private baccalaureate colleges. The latter category includes some institutions with selective admissions, but a vast majority are not.

Just because presidents generally support affirmative action does not mean they are confident that Harvard will successfully defend its practices -- or that Asian Americans don't face discrimination in selective college admissions.

Barely more than a third of campus leaders, 37 percent, agree or strongly agree with the statement that they "feel confident in Harvard's defense of itself and the principles behind affirmative action"; 27 percent disagree or strongly disagree, and 35 percent are neutral. Harvard's private university peers (46 percent) and presidents of public doctoral institutions (44 percent) were likeliest to agree.

Forty-two percent of chief executives -- virtually identical across sectors -- strongly agree or agree that "Asian American applicants to top colleges face discrimination," while fewer than a quarter disagree.

Their skepticism about Harvard's chances at trial, however, doesn't mean the institutions are preparing for life without affirmative action. Barely one in seven presidents, 13 percent, said their institution is "planning for the possibility that courts may limit or bar the consideration of race in admissions and financial aid," with the proportion highest at public doctoral universities, where a quarter of presidents said they were preparing for that possibility.

The Harvard lawsuit and the possibility that affirmative action could be undermined has brought renewed attention to the issue of admissions preferences for the children of alumni, which some advocates for affirmative action see as a form of favoritism for those who have historically fared best in higher education -- "a system of inherited privilege that benefits rich whites at the expense of almost everyone else," as Nicholas Kristof put it in The New York Times last fall.

About half of college presidents (52 percent) said they believe it is appropriate for private colleges to consider legacy status in admissions, although private college leaders (60 percent) and those at public doctoral universities (65 percent) were much likelier than those at community colleges (38 percent) and public four-year colleges (44 percent) to agree.

Only a quarter of campus chief executives, 24 percent, agreed that it was appropriate for public colleges to consider legacy status in admissions.

Race and Religion

A ruling in the Harvard case limiting or barring the use of affirmative action could spur a wave of racial unrest on college campuses -- at a time when presidents seem to believe race relations on their campuses are improving.

As seen in the chart below, college and university leaders assessed the state of campus race relations more positively this year after a record low last year, with a quarter deeming race relations on campuses nationally as excellent (1 percent) or good (24 percent). Sixty-six percent declared them to be fair and 9 percent poor. Fifteen percent of the presidents of private four-year colleges rated campus race relations as poor.

It occurs frequently in Inside Higher Ed's surveys that respondents believe their own institutions' situations to be better than the national outlook. Indeed, four in five presidents -- similarly across sectors -- believe race relations on their own campuses to be excellent or good.

Women and younger presidents portrayed the situations on their campuses less positively. While 84 percent of male presidents described race relations on their campus as being good (66 percent) or excellent (18 percent), only 72 percent of women did (16 percent excellent, 56 percent good).

Beverly Daniel Tatum, president emerita of Spelman College and an author and expert on campus race relations, said via email that when reading about the presidents' confidence in their own campus's race relations, "I find myself imagining what the presidents of those colleges with racist images in their yearbooks would have said about race relations on their campuses during that time period? Are today's presidents really tuned in to what is happening in residence halls and fraternity houses and on student social media in the Trump era?"

"Do presidents feel that race relations are excellent or good because they have created dynamic opportunities for cross-racial engagement on campus, both in and outside the classroom, or because the campus is quiet and protests have subsided? I would be very curious to know what the indicators are that presidents are using when they answer these questions."

The phenomenon of presidents expressing more confidence in their own campus than in the larger environment is evident on another campus climate issue: perceived rising anti-Semitism. Incidents involving vandalism or swastika painting surged before and after last year's deadly shooting at a Pittsburgh synagogue, sometimes prompting questions about whether administrators are taking the situations seriously enough.

Roughly two-thirds of college and university leaders told Inside Higher Ed that they viewed anti-Semitism increasing "a lot" (12 percent) or "a little" (53 percent) on campuses nationally in the last few years, with the figure at about 80 percent for leaders of public doctoral and master's/baccalaureate colleges.

But asked about anti-Semitism on their own campuses, barely one in 10 presidents (12 percent) perceived an increase, though the figure was roughly double at public doctoral (24 percent) and public master's/baccalaureate (22 percent) institutions.

What explains the gap? Human nature, says Mark Yudof, former president of the University of California and the University of Texas systems.

"There is a tendency of campus presidents to treat racist and anti-Semitic occurrences on their own campuses as aberrational (unfortunate one-off events) while seeing similar events on other campuses across the country as more systemic (proverbial tips of the iceberg)," he said via email. "In terms of anti-Semitism, I have noted the same uptick that the presidents perceive: more swastikas, more scrawled hate and more anti-Semitic narratives in discussions of Israel. One of the challenges is to make sure campus deans of students and equity and inclusion officers appreciate the offense that is given to Jewish students, faculty and staff (and the larger Jewish community) and take steps to make ensure they are not alienated from the campus community."

Growing Confidence (in Parts of the Country)

The last few weeks have seen another uptick in the number of colleges closing or announcing significant financial cutbacks -- mostly small private colleges, but some regional public institutions, too.

But in their annual answers to Inside Higher Ed's equivalent of a consumer confidence survey, presidents indicated growing confidence in their institutions' financial stability. As seen in the graphic below, more presidents this year strongly agreed or agreed with the statement that "I am confident my institution will be financially stable" over five and 10 years than they have since Inside Higher Ed first asked the question in 2014.

Private college presidents are more upbeat than their peers at public institutions are, with 60 percent of private college leaders confident in their institution's financial stability versus 52 percent of public institutions' chiefs. The same eight-percentage-point difference was evident in 2018, when the margin was 55 percent to 47 percent.

Asked to predict how many campuses will close or merge in 2019, presidents envisioned slightly fewer public college mergers and slightly more closures and private college mergers than they foresaw for 2018 at this time last year. (The survey was conducted before a flurry of closures and reductions this winter involving Green Mountain and Hampshire Colleges, among others.)

And roughly the same proportion of presidents -- about one in seven -- said they could envision their institution "closing or merging in the next five years." Presidents at public doctoral universities were the outlier on this question, with just 1 percent envisioning their institutions closing.

Presidents' age and gender influenced their financial outlooks to some extent. Men were 10 percentage points likelier (61 percent versus 51 percent) to express confidence in their institutions' financial sustainability over a decade, for instance.

And presidents under 60 were notably likelier to envision significant numbers of colleges closing this year: 39 percent of them predicted at least 11 closures (10 percent predicted more than 20), while just 26 percent of presidents 60 and over foresaw more than 10 closures.

Higher ed financial experts said they had a hard time seeing evidence to support the presidents' increased optimism, modest as it is.

“It is interesting to see the shift in positive sentiment,” said Susan Fitzgerald, associate managing director at Moody’s Investors Service, which rates the bonds of hundreds of the nation's colleges and universities. “While there are some stabilizing elements in the current, more favorable environment for state support and gifts, approximately one-fifth of both public and private colleges are still struggling to balance their budgets. The situation will only become more challenging if economic growth slows or if financial markets remain volatile, particularly for colleges in the Northeast and Midwest, which also confront difficult demographics.”

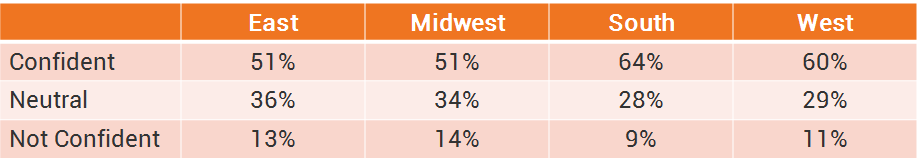

Indeed, presidents of colleges in the East and Midwest are less likely than their peers in the South and West to express confidence in their 10-year financial stability, as seen in the table below.

% of Presidents Expressing Confidence in Financial Stability Over 10 Years, by Region

Fun With the Feds

This year's survey gauged presidents' perceptions of federal policy halfway through the Trump administration -- and as a divided Congress began its work.

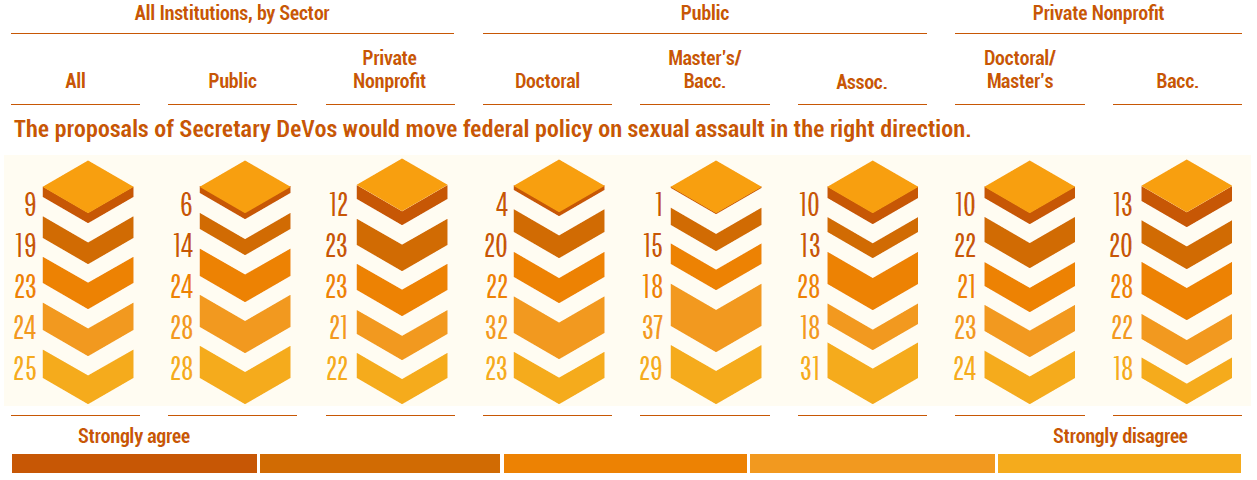

On the subject of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos's approach to regulating campus policies on sexual assault -- which the secretary argued would restore fairness to the process of adjudicating complaints, but victims' advocates say would undermine the rights of survivors -- college leaders are more likely to oppose than to favor it.

Roughly half of presidents -- slightly more at public than at private colleges -- disagree that the DeVos proposals would "move federal policy on sexual assault in the right direction," while 28 percent agree or strongly agree.

More than half of presidents -- 62 percent at public institutions and 49 percent at private nonprofit ones -- said they believed the Education Department's proposals would result in fewer complaints being filed by students who say they've been assaulted or harassed.

Skeptical as they are about the wisdom of the DeVos proposals, though, campus leaders say some action was needed to correct overzealousness on the part of the Obama administration on campus sexual assault. Half of all presidents -- 42 percent of public university leaders and 60 percent of those at private colleges -- agree or strongly agree that "the Obama administration's approach did not place enough emphasis on due process for those accused of sexual assault or harassment."

Terry Hartle, senior vice president for government and public affairs at the American Council on Education, said the presidents' mixed views on federal sexual assault policy reflect the complexity of the issue. "Many presidents felt that the Obama guidance did not give adequate attention to the rights of the accused, but they are also concerned that the Trump administration’s rewrite may have gone too far in the other direction and think that this package might do more harm than good," he said. "Finding the right balance that will work well for all campuses, all parties and in every case is going to be a very tall order."

Campus leaders have generally modest expectations for what the new, divided Congress will achieve. Between a quarter and about a third of presidents say they expect the new Congress to:

- pass budgets that are generally favorable to institutions like theirs (25 percent over all, with community colleges most optimistic at 34 percent).

- "approve legislation that will generally help my institution" (24 percent over all, and just 14 percent for public master's/baccalaureate institutions).

- pass legislation to renew the Higher Education Act (37 percent).

Improving Image?

Public opinion polls continue to show waning confidence in American colleges and universities, especially among Republicans. But campus leaders seem less worried about those results -- or maybe they're just getting used to them.

Just 16 percent of college presidents agree with the statement that "most Americans have an accurate view of the purpose of higher education," and 50 percent disagree (12 percent strongly). Fewer than one in five presidents (18 percent) say that Americans understand the purpose of their sector of higher education, with the proportions ranging from 8 percent for private four-year colleges to 26 percent for community colleges.

"The fact that college and university presidents believe that American public does not know the truth about institutions of higher education is not surprising," said Noah Drezner, an associate professor at Teachers College of Columbia University, who has written about public attitudes and higher ed finance. "The results of the survey of college presidents and these other studies indicate that institutions and the sector as a whole are not good storytellers. Individual colleges and universities as well as our sector have many good stories to share -- not only the individual benefits that come with a college degree but the advances for all of society. However, the media and many politicians across the political spectrum steer the narrative away from those good stories."

As seen in the table below, majorities of college presidents continue to believe that the public misunderstands how expensive higher education is, how wealthy colleges and universities are, and whether colleges and universities are spending money on the wrong things (think lazy rivers).

They also remain worried about Republicans' growing skepticism of higher education, and perceptions that higher education is inhospitable to alternative (read: conservative) viewpoints.

But in several of these cases -- regarding endowments, the explosion of amenities, and Republican skepticism -- presidents seem considerably less worried this year than last.

In other cases, though, presidents aren't resting easy, and in fact their own doubts seem to be growing.

The proportion of campus leaders who say that higher education is perceived as intolerant of conservative views actually increased, to 37 percent from 32 percent in 2018. Presidents of private nonprofit colleges and universities (40 percent) are likelier than their public college peers (33 percent) to answer this way. Male presidents were significantly likelier to strongly agree than were female presidents, by a margin of 15 to 3 percent.

Lanae Erickson, senior vice president for social policy and politics at Third Way, a public policy group in Washington, called the overall decline in worry about Republicans' views a sign -- despite President Trump's recent vow to withhold research funds from campuses that are perceived as hostile to free speech -- that "those concerns just seem to have gone down significantly over the past year."

But she noted that public college presidents remain significant more worried about Republican attitudes than their private college counterparts do, by a margin of 74 to 61 percent.

"That indicates to me their worry might be more focused on state funding levels than free speech," she said. "If they are concerned about state-level Republicans disinvesting from higher ed, that’s in many ways a more serious threat to their schools than this sensational free speech/liberal bias debate."

Other Highlights

The survey touched on a range of other issues. Among them:

Philanthropy. Michael Bloomberg's $1.8 billion donation to Johns Hopkins University last fall renewed debate about whether wealthy Americans are using their money optimally to help students and colleges.

Presidents overwhelmingly agree that "the largest gifts to higher education would do more good if they went to nonelite institutions." Unsurprisingly, public college and university leaders were likelier than their private college peers to agree with that statement, by a margin of 82 to 74 percent, but the consensus was notable.

On a related question, whether the wealthiest institutions in higher education receive too large a share of philanthropic dollars, the divisions were a bit starker. Presidents from the sectors that include the most wealthy institutions, public doctoral universities (67 percent) and private baccalaureate colleges (70 percent), were least likely to hold that view, while leaders of community colleges (81 percent) and public master's/baccalaureate colleges (82 percent) were most likely.

Presidents also responded to a series of questions about whether donors are demanding more control and attaching more inappropriate requirements to their gifts.

A plurality of presidents, 40 percent, agreed that donors of large gifts are making more such demands than in the past (27 percent disagreed), with private college presidents much less likely to agree (34 percent) than public campus leaders (46 percent).

About a third of presidents (34 percent) said they had personally rejected financial gifts because of strings that would have been attached about how the funds could be used, with a majority of private doctoral/master's university leaders (53 percent) concurring.

Foreign Ties. The gruesome death of Jamal Khashoggi, a Saudi dissident and journalist, put pressure on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and other institutions to reassess their ties to countries with dubious human rights records.

About two-thirds of campus chief executives strongly agree (37 percent) or agree (27 percent) that colleges and universities should "reconsider their involvement with countries that do not respect basic human rights." Community college leaders agreed most strongly (70 percent), those at private baccalaureate institutions less so (52 percent).

Support was weaker, but still solid, for the notion that colleges should not set up branch campuses in such countries, with 55 percent of presidents agreeing.

Andrew Ross, a professor of social and cultural analysis at New York University who has strongly criticized that university's international expansion into the Middle East and Asia, said the presidents' answers reflected what he characterized as a newfound cautiousness that is slowing the rush to build branch campuses abroad.

"Programs are not being set up at the same rate as they once were," he said, a reflection that universities have not seen the financial and other payoffs they envisioned a decade and more ago. "One would hope there would be certain reluctance to help countries edu-wash their human rights records."

Textbook Affordability. Presidents overwhelmingly agree (87 percent) that textbooks and course materials cost too much, and they support the use of open educational resources -- free and openly licensed digital curricular materials that can be shared and remixed -- with similar enthusiasm (85 percent).

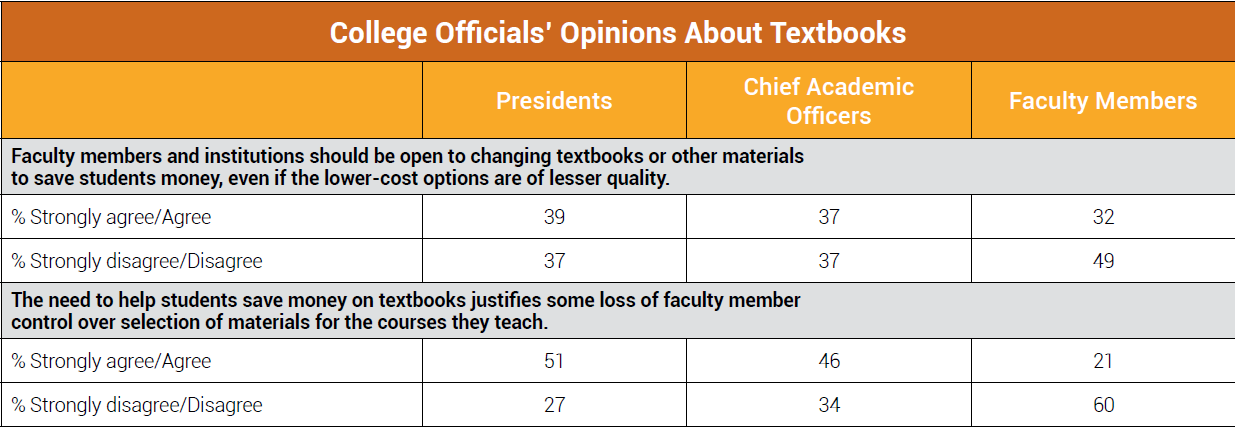

They are evenly divided, though, on how that philosophical support should drive behavior -- theirs and their faculty's. Roughly similar proportions of presidents agree (39 percent) and disagree (37 percent) with the view that "faculty members and institutions should be open to changing textbooks or other materials to save students money, even if the lower-cost options are of lesser quality." (Public college and university leaders are 10 percentage points likelier to support that idea, by 45 to 35 percent.)

They are about twice as likely as not (51 percent to 27 percent) to agree that "the need to save students money on textbooks justifies some loss of faculty member control over selection of materials for the courses they teach." On that score, they differ from faculty members themselves, who responded to the contrary in Inside Higher Ed's 2018 Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology last fall, as seen in the table below.

Preparation for the Job. Asked to rate how well prepared they felt on a range of fronts for their first presidency, campus leaders expressed the most comfort with their readiness to work with faculty members (84 percent) and handle academic affairs (83 percent), likely reflecting the fact that many of them rose from provost positions.

Two-thirds or more said they felt prepared for financial management and admissions and enrollment management (68 percent). Slightly fewer than a third said they were well prepared to work with trustees (64 percent) and for public and media relations (59 percent).

About half said they were ready to deal with issues such as race relations (52 percent), athletics (51 percent), hot-button student affairs issues like sexual assault or drinking (51 percent), and government relations (50 percent).

Forty-nine percent thought they were well prepared for digital learning, and 48 percent for fund-raising (!).